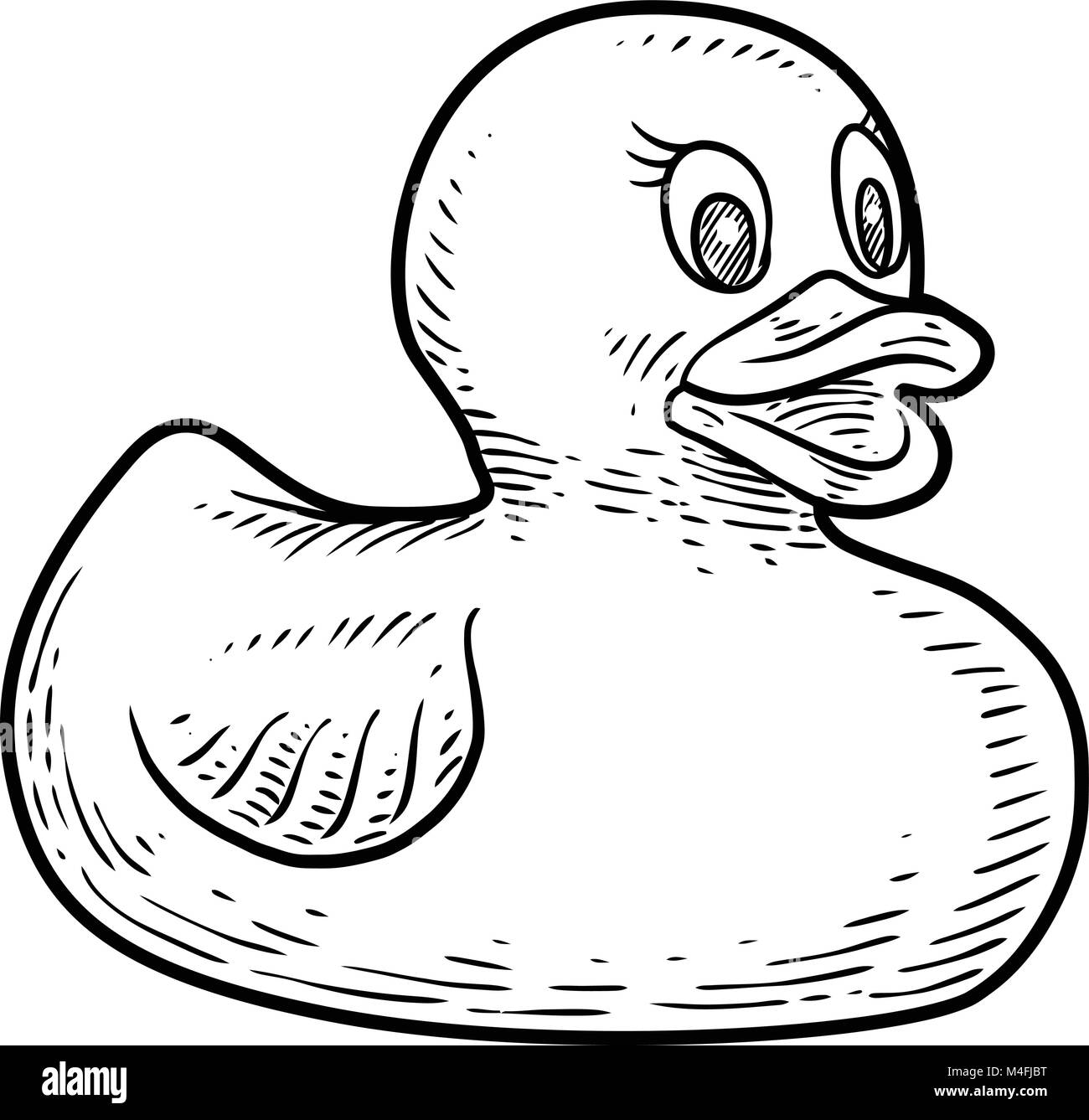

Let’s be real. If you pick up a pencil to doodle, a rubber duck is probably one of the first things that pops into your head. It’s a universal icon. We see that bright yellow silhouette and immediately think of bubble baths, Ernie from Sesame Street, or maybe that weirdly famous "Rubber Duck" giant floating installation by Dutch artist Florentijn Hofman. But here’s the thing about drawings of rubber ducks: they are deceptively difficult to get right.

Most people start with a circle for the head and a bigger oval for the body. Simple, right? Not really. When you actually look at a physical rubber duck, you realize it’s a masterclass in organic curves and synthetic lighting. It isn't just a bird; it's a plastic interpretation of a bird. That distinction matters. If you draw a real mallard, you’re looking at feathers and anatomy. When you’re working on drawings of rubber ducks, you’re actually trying to replicate the way light bounces off injection-molded polyvinyl chloride.

The Anatomy of the Squeak

What most people get wrong is the neck. In a standard rubber ducky, the neck isn't really a neck at all. It’s a structural transition point that has to look thick enough to support a heavy head but flexible enough to suggest it could squeak if you squeezed it.

I’ve seen thousands of sketches where the artist makes the beak too realistic. Don't do that. A rubber duck's beak is usually a blunt, rounded orange nub. It lacks a cere or realistic nostrils. If you add too much detail to the face, the "uncanny valley" effect kicks in. It stops looking like a toy and starts looking like a strange, yellow biological mutation. Stick to the simplified geometry.

Think about the "waterline" too. Even if you aren't drawing the duck in water, the bottom is almost always flat. This is a design feature from the original 1940s patents—most notably the work of Peter Ganine. He was a sculptor who patented a floating duck toy that actually stayed upright. Before him, toy ducks would often tip over and "drown." When you’re composing drawings of rubber ducks, that flat base provides a sense of weight and "toy-ness" that a rounded bottom lacks.

📖 Related: Shellac Prayer to God: Why This Rare Restoration Habit is Making a Comeback

Lighting the Yellow Void

Yellow is a nightmare for artists. Honestly, it's the hardest color to shade. If you use black to shade yellow, it turns into a muddy, sickly green. If you use brown, it can look dirty. Professional illustrators often use a warm purple or a deep orange for the shadows on a yellow object. This creates a "complementary" contrast that keeps the yellow looking vibrant and clean.

Reflective highlights are your best friend here. Because these toys are glossy, they have sharp, white "specular highlights." These are those little white glints that tell the viewer's brain, "Hey, this object is smooth and shiny." Without those glints, your drawing will look like a flat yellow blob.

Different Styles for Different Vibes

- The Classic Cartoon Look: Thick black outlines. No gradients. Just solid yellow, solid orange, and maybe a little blue "splash" at the bottom. This is great for stickers or quick icons.

- Hyper-Realism: This is where you focus on the "seam." Every mass-produced rubber duck has a faint line where the two halves of the mold met. Including that tiny detail makes the drawing look incredibly authentic.

- The Gritty Reboot: Believe it or not, there's a whole subculture of "punk" or "horror" rubber duck art. Think cracked plastic, missing eyes, or neon-colored "zombie" ducks.

Why We Are Obsessed With This Shape

The obsession with drawings of rubber ducks isn't just a coincidence. It’s linked to "kawaii" culture and the psychology of rounded shapes. Humans are evolutionarily hardwired to find round, soft things non-threatening. A rubber duck is basically a collection of spheres. There are no sharp edges.

In the world of software engineering, there’s even a thing called "Rubber Duck Debugging." Programmers carry a little duck around and explain their code to it line by line. When they hit a mistake, they usually find it because they had to vocalize it to the duck. This has led to a massive spike in duck-related office art and digital illustrations. It’s become a symbol of problem-solving.

Mastering the Perspective Shift

The trickiest angle is the three-quarter view. This is when the duck is facing slightly away from you. You have to balance the curve of the chest with the protrusion of the tail. If you get the perspective wrong, the duck looks like it’s warping through a black hole.

Try this: Draw the "footprint" first. Even though it's a floating toy, imagine it sitting on a piece of paper. If you can map out that flat oval on the ground, building the rest of the body on top of it becomes a lot easier.

Tools of the Trade

If you're going digital, use a soft round brush for the main body but a hard-edged brush for the highlights. Procreate users often swear by the "Studio Pen" for the outlines because it has a slight taper that mimics the way a real pen moves.

For traditional artists, Copic markers are the gold standard for drawings of rubber ducks. The "Y" series (Y06, Y08, Y17) provides that perfect "school bus yellow" that defines the genre. Just make sure you let the ink dry before you go in with a white gel pen for the highlights, or you’ll end up with a blurry mess.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Proportions: Making the head too small. A rubber duck is "chibi" by nature. The head should be nearly as large as the body.

- The Beak Bridge: Real ducks have a slope from the forehead to the beak. Rubber ducks usually have a sharp "step" or a very distinct 90-degree-ish angle where the beak joins the face.

- The Eye Placement: Don't put the eyes on the front of the face like a human. They need to be on the sides of the head. Even in a simplified drawing, putting them too close together makes the duck look like a person in a mask.

Improving Your Duck Drawings Today

If you want to actually get better at this, stop drawing from memory. Go to a dollar store, buy a pack of three ducks, and put them under a desk lamp. The harsh light will show you exactly where the shadows fall.

Notice how the light bounces off the table and back onto the bottom of the duck. This is called "reflected light." Adding a tiny bit of "bounce light" to the underside of the duck’s belly will make it look 3D instantly. It’s a professional trick that separates amateurs from people who actually know what they’re doing.

Actionable Steps for Better Duck Art:

- Simplify the base: Start with a flat-bottomed bean shape for the body.

- Focus on the Seam: Draw a very faint vertical line down the center of the head and body to represent the plastic mold line; it adds instant realism.

- Limit your Palette: Use only three shades of yellow (highlight, mid-tone, shadow) and two shades of orange.

- Kill the Symmetry: In real life, toys are often slightly warped. A perfectly symmetrical duck looks boring. Give it a tiny bit of "lean."

- Environment Matters: Even a simple blue shadow underneath the duck makes it feel like it's actually "weighted" in space rather than floating in a white void.

Whether you're doing this for a technical manual, a children's book, or just because you're bored in a meeting, remember that the "rubber" part of the name is the most important. It’s a man-made object. Treat it like one. Focus on the shine, the seams, and those simplified, chunky curves.