Most people think they know what a fish looks like. You’ve seen them in tanks, on plates, or darting through a lake. But the moment you sit down to start a drawing of a fish, you realize your brain has been lying to you. We don't see the world; we see icons of things. We see a "fish shape"—that football with a triangle on the end we all learned in kindergarten.

Drawing is actually about unlearning those icons.

It’s about looking at a Bluegill or a Betta and realizing the eye isn't just a circle. It's a complex, gelatinous sphere tucked under a bony ridge. If you want to get good at art, honestly, skip the faces for a week. Draw a trout instead. Fish are the ultimate masterclass in texture, fluid dynamics, and subtle anatomical transitions. They are basically wet, iridescent tubes of muscle, and capturing that on paper is harder—and more rewarding—than it looks.

The Anatomy Most People Get Wrong

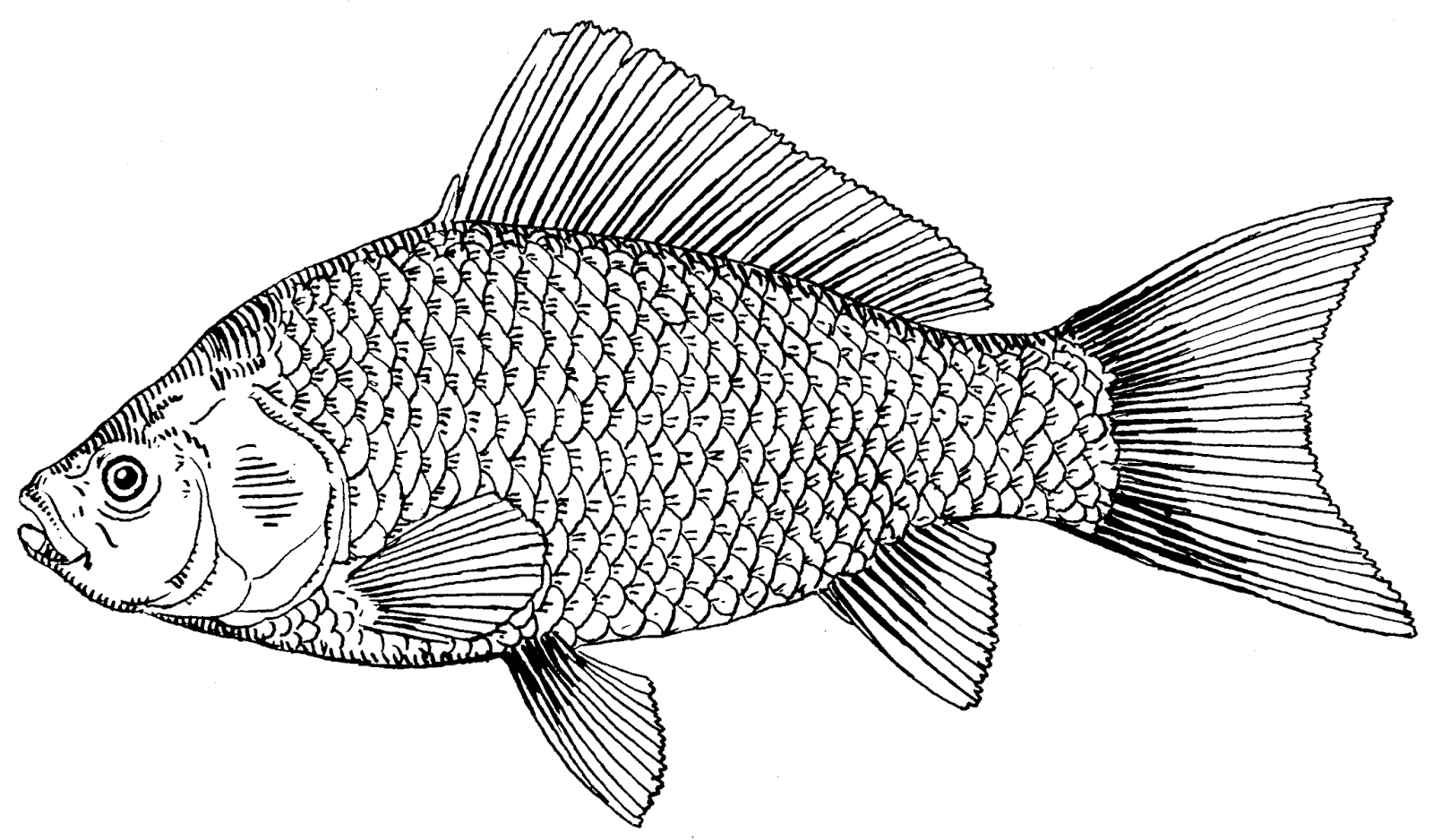

You’ve probably seen a thousand fish drawings where the fins just sort of... sprout out of the side like leaves on a branch. That’s not how it works. Fins are extensions of the internal skeletal structure. If you look at the work of famous naturalist illustrators like Louis Agassiz or the detailed plates in Marcus Elieser Bloch’s Allgemeine Naturgeschichte der Fische, you see the "attachment points."

The pectoral fins don't just sit on the skin. They are anchored to the shoulder girdle, just behind the gills. When you’re working on a drawing of a fish, you have to find that anchor. If you don't, the fish looks like a toy. It won't look like it can actually push water.

And let's talk about the "Lateral Line."

Many hobbyists completely forget this exists. It’s a faint, often dark or textured line running down the side of the body. It’s a sensory organ. In species like the Striped Bass, it’s a defining feature. If you leave it out, the fish looks naked. If you overdraw it, it looks like a zipper. The trick is to keep it subtle—a break in the scale pattern rather than a hard pencil stroke.

✨ Don't miss: Green Emerald Day Massage: Why Your Body Actually Needs This Specific Therapy

Why Scale Patterns Are a Trap

Don't draw every scale. Just don't.

It’s the most common mistake in a drawing of a fish. You spend four hours meticulously cross-hatching every tiny scale on a Carp, and the result looks like a chainmail suit. It loses all its "fishiness." Real fish are slimy. They reflect light. When light hits a wet surface, it blows out the detail in some areas (the highlights) and compresses it in others.

Try this instead.

Focus on the "shimmer." Pick a few areas—usually along the curve of the back or the thickest part of the belly—to suggest the scale pattern. Use a sharp 2B pencil or a fine-liner to hint at the overlapping edges. Then, let the rest of the body dissolve into soft gradients. This creates the illusion of a reflective, organic surface. Professional illustrators call this "suggested detail," and it’s what separates a technical diagram from a piece of art that actually feels alive.

The Fluidity of the Fin

Fins are not stiff fans. Even when they are extended, they have a rhythmic, undulating quality. Think of them like silk underwater.

If you’re sketching a Betta fish, the fins are the whole show. You’re dealing with "fin rays"—those bony spines that support the membrane. To make them look real, vary the pressure of your stroke. The ray should be thicker at the base and taper to almost nothing at the edge.

🔗 Read more: The Recipe Marble Pound Cake Secrets Professional Bakers Don't Usually Share

Pro tip: Always draw the direction of the water first.

If your fish is swimming hard, the fins should be swept back. If it’s hovering, the pectorals might be flared out. It’s about physics. A drawing of a fish that ignores water resistance will always look like it’s floating in a vacuum. You want it to look like it’s displacing mass.

Different Species, Different Challenges

Every fish has a "personality" in its silhouette.

- The Predator (Shark, Pike, Tuna): These are built for speed. Use long, sweeping gestures. The lines should be sharp and aggressive. The "fusiform" body shape—tapered at both ends—is key here.

- The Bottom Feeder (Catfish, Flounder): These are all about weight and texture. The shapes are flatter. The eyes are often positioned differently to look upward.

- The Ornamental (Goldfish, Angelfish): Here, you focus on the flow. The anatomy is often bred to be exaggerated, so you can lean into the decorative curves.

Honestly, start with a Mackerel. They have beautiful, simple lines and a distinct "tiger stripe" pattern on the back that is incredibly satisfying to shade. It teaches you about value contrast without being overwhelmingly complex like a Seahorse might be.

Tools of the Trade

You don't need a $200 set of markers.

A simple graphite pencil (HB and 4B) and a good kneaded eraser are enough. The eraser is actually your most important tool for a drawing of a fish. Why? Because fish are shiny. You’ll use the eraser to "carve out" the highlights on the wet skin and the reflective spots on the eyes. If you’re feeling fancy, a white gel pen for the final "pop" on the scales makes a massive difference.

💡 You might also like: Why the Man Black Hair Blue Eyes Combo is So Rare (and the Genetics Behind It)

If you prefer digital, use a brush with some grain. Perfectly smooth digital gradients often make fish look like plastic. You want a bit of "noise" to mimic the organic imperfections of skin and slime.

Common Misconceptions About Fish Art

People think fish are easy because they don't have limbs like dogs or humans.

Actually, the lack of limbs makes the "line of action" even more important. If the spine of your fish drawing is a straight line, it’s dead. It looks like a trophy mounted on a wall. To give it life, you need an "S-curve." Even a slight bend in the body suggests a heartbeat, a flick of the tail, a moment of life.

Also, the eye.

Don't put the eye right on the front of the face unless it's a predator that needs binocular vision (and even then, it's rare in fish). Most fish have eyes on the sides of their heads. Understanding the placement of the "orbital bone" helps you realize how the head transitions into the torso. It’s a seamless flow, not a "head" attached to a "body."

Actionable Steps for Your Next Sketch

If you're ready to start your next drawing of a fish, stop looking at other drawings.

Go to the source.

- Find High-Res Reference: Use sites like FishBase or National Geographic. You need to see the actual biological structure, not someone else's interpretation of it.

- Gesture First: Spend 30 seconds drawing just the curve of the spine and the general oval of the body. If the "vibe" isn't right in 30 seconds, a hundred hours of scale detail won't fix it.

- Map the Fins: Lightly mark where the fins anchor to the body. Check the symmetry. If you see the top dorsal fin, where would the pelvic fins be on the underside?

- Tone and Texture: Instead of coloring it in like a coloring book, think about the light source. Is the light coming from above (the surface of the water)? If so, the belly should be in shadow. This is called "counter-shading," and it’s how fish camouflage themselves in the wild.

- The Final Glimmer: Use your brightest white to hit the very top of the eye and the leading edge of the fins.

Focusing on these structural realities transforms a simple hobby into a study of the natural world. It’s not just about making a pretty picture; it’s about understanding how life moves through a medium much denser than our own. Next time you see a fish, don't just see a "fish." See the overlapping plates, the translucent rays of the fins, and the way the light fractures across a wet surface. That's when the drawing really begins.