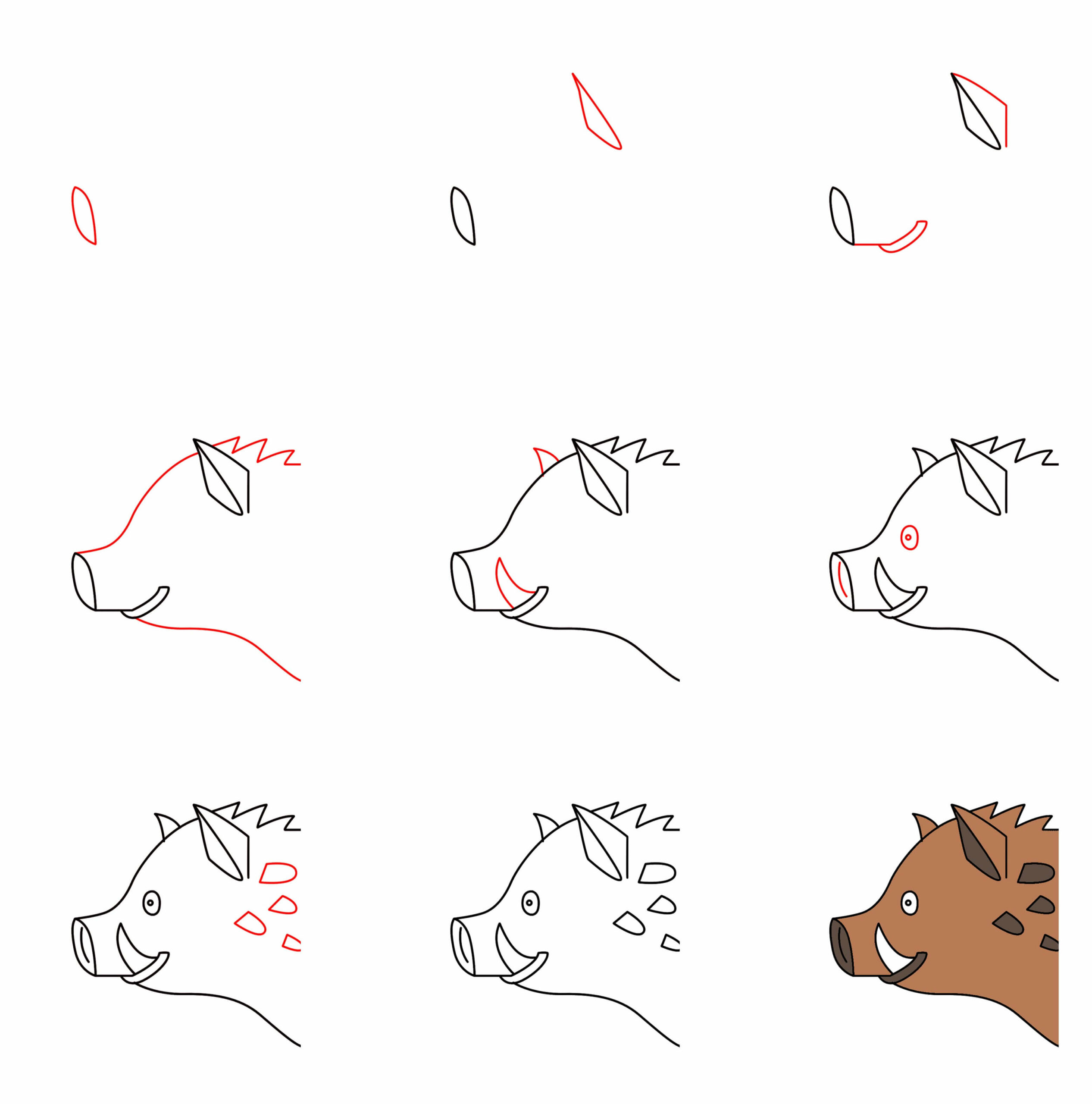

Drawing a wild boar is a massive ego check for most artists. Honestly, it’s not like sketching a pig. You can’t just draw a pink oval, add a curly tail, and call it a day. Boars are dense, muscular tanks of the forest. They have this specific, aggressive anatomy that feels more like a prehistoric beast than a farm animal. If you get the proportions wrong, your drawing of wild boar ends up looking like a very sad, hairy potato.

Most people fail because they focus on the hair. They see that coarse, dark coat and start scribbling. Stop. Before you even touch the texture, you have to understand what is happening underneath that bristly fur.

The Brutal Anatomy of a Forest Tank

Wild boars are front-heavy. That is the golden rule. If you look at a Sus scrofa—the Eurasian wild boar—the shoulder height is significantly taller than the rump. This gives them a "wedge" shape. It's built for bulldozing through thick underbrush. When you start your drawing of wild boar, your initial gesture lines should look like a tilted rectangle or a heavy wedge.

The skull is a masterpiece of evolution. It’s elongated and straight. Unlike a domestic pig, which often has a "dished" or concave facial profile, the boar's snout is a straight shot from the forehead to the disk of the nose. This is for rooting. It's a tool.

Then there are the tusks. These aren't just for show. Lower canines curve upward, and they actually sharpen themselves against the upper canines every time the boar closes its mouth. It’s a literal self-sharpening knife system. When you're sketching these, remember that the "lip" of the boar often covers the base of the tusk. Don't just stick them on the outside of the face like stickers; they emerge from the jaw.

The "Mane" Event

The ridge of hair along the spine is what gives the boar its silhouette. In the winter, this coat is incredibly thick. In the summer, they look almost naked and surprisingly lean. If you are drawing a winter boar, that ridge (the "bristles") can stand up when the animal is agitated. This isn't just fluffy fur. It’s stiff. It’s coarse.

Try using flicking motions with a 2B or 4B pencil. Don't draw every hair. You'll lose your mind. Instead, draw the clumps. Shadow the underside of the hair clumps to give them volume.

Lighting and the "Dark Vacuum" Problem

One of the hardest parts of a drawing of wild boar is the color. They are usually dark brown, black, or a muddy gray. If you shade the whole thing one dark tone, you lose all the muscle definition. It becomes a silhouette.

Professional illustrators, like those who do scientific plates for organizations like the Smithsonian, use "rim lighting." Basically, you imagine a light source behind the boar that catches the edges of those coarse hairs. This separates the dark body from the dark background.

Think about the environment. Boars love wallowing. This means their lower half is often caked in dried mud. This is a gift for an artist! It provides a lighter, matte texture against the darker fur. Use a kneaded eraser to lift highlights out of the "muddy" areas on the legs and belly. It adds instant realism.

Feet and the "Dewclaw" Detail

Don't draw horse hooves. Boars have four toes, but they walk on the middle two. The outer two—the dewclaws—are higher up on the leg. However, in soft mud, those dewclaws leave marks. If your drawing includes a muddy ground plane, adding those extra little "dots" behind the main hoof print tells the viewer you actually know your biology. It's a small flex, but it works.

Common Mistakes That Kill the Realism

I see this a lot: people make the eyes too big.

Boars have relatively small eyes. They are set high and back on the head. Because they rely more on scent and hearing, the eyes don't dominate the face. If you draw big, soulful eyes, you've just drawn a Disney character, not a wild hog. Keep them small, dark, and somewhat "buried" under the brow ridge.

🔗 Read more: Why Your Bratwurst and Sauerkraut Recipe Always Tastes Missing Something

Another big one? The tail. A wild boar's tail is straight. It ends in a tuft of hair. It does not curl like a pig's tail. If you put a curly tail on a wild boar, you've fundamentally misunderstood the animal. It’s the quickest way to ruin the "wild" vibe of your piece.

Using Reference Without Copying

Look at the work of wildlife artists like Robert Bateman or even the cave paintings in Lascaux. Those ancient artists got the "heaviness" of the boar right with just a few charcoal lines. They emphasized the hump of the neck.

When you look at a photo, don't just trace it. Look for the "tension" points. Where is the weight shifting? Boars are surprisingly fast. If you're drawing one in motion, the legs should look powerful, not spindly. The ankles (fetlocks) are thick.

Materials and Techniques for Texture

If you're working digitally, use a "raking" brush. This mimics the multiple strands of coarse hair. If you're using traditional graphite or charcoal:

- H-grade pencils: Use these for the initial structural sketch. They don't smudge as much.

- Carbon pencils: These give a deeper, matte black than graphite, which is perfect for the darkest parts of the boar's coat.

- A stiff bristle brush: You can actually use a dry paintbrush to smudge charcoal in a way that looks like fur texture.

The snout is a different texture entirely. It’s leathery. It should have a slight sheen to it, especially if it’s wet. Use a very sharp pencil to create tiny, circular "pores" on the nose disk. This contrast between the leathery nose and the wire-like hair makes the drawing pop.

Taking the Next Steps

Stop thinking about it as a "pig drawing." Start thinking about it as a study of power and weight.

To really master this, go beyond a single sketch. Fill a page with just snout studies. Then a page of just hooves. Understanding how the joints move in a trot versus a charge will change how you position the body.

Check out the "Animal Anatomy for Artists" by Eliot Goldfinger. It's basically the bible for this stuff. It shows the muscular structure of the suidae family in detail. Once you see where the masseter muscle (the jaw muscle) sits, you'll understand why the head is shaped the way it is.

🔗 Read more: Self Flagellation: Why Humans Have Used Pain to Seek Clarity for Centuries

Go get some heavy-grain paper—something with a bit of "tooth." The rougher the paper, the better it will hold the charcoal and mimic that gritty, forest-floor texture that defines the life of a wild boar. Keep your lines bold. A boar isn't a delicate creature; your drawing shouldn't be either.