You're standing in Highland Park. The sky turns a bruised shade of purple, that weird eerie glow we all recognize right before a lake-effect wall hits. You pull out your phone, refresh the map, and see a massive blob of green and yellow heading straight for the 585. But here’s the thing: that little animation on your screen isn't just a picture of rain. It’s a complex calculation of microwave radiation bouncing off ice crystals and water droplets, processed by a massive spinning dish located out in Buffalo or Montague. If you’ve ever wondered why the "Doppler radar Rochester NY" search doesn't always match what’s actually falling on your driveway, it’s because Rochester is in a bit of a geographic "radar gap" that most people don't even realize exists.

It’s frustrating.

Most of us rely on the National Weather Service (NWS) or local news apps, assuming there’s a giant radar tower sitting right in the middle of Center City. There isn’t.

The Buffalo Connection and the Curvature Problem

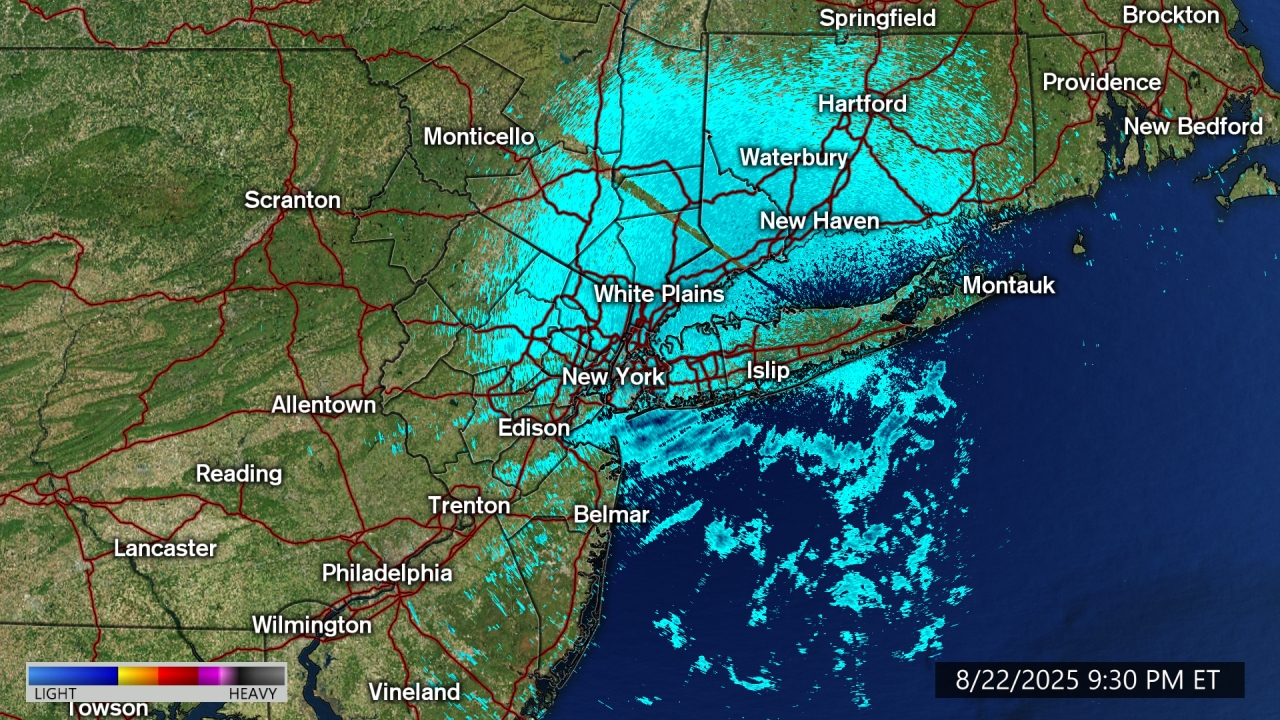

Rochester doesn't have its own dedicated NEXRAD (Next-Generation Radar) station. Instead, we are primarily served by KBUF, located at the Buffalo Niagara International Airport. When you look at a radar map for Rochester, you're usually seeing data from 60 miles away.

This creates a significant technical hurdle: Earth is round.

Radar beams travel in a straight line. Because the earth curves away beneath the beam, the further you get from the source, the higher the beam sits in the sky. By the time the signal from Buffalo reaches Monroe County, it’s often several thousand feet above the ground. If a low-level snow squall is hugging the Lake Ontario shoreline at 1,500 feet, the Buffalo radar might overshoot it entirely. This is exactly why you'll see "clear skies" on your app while you're actively shoveling three inches of powder. It's not a glitch in the software; it's basic geometry.

The physics here is called the Doppler Effect. Named after Christian Doppler, it’s the same reason a siren changes pitch as it passes you. The radar sends out a pulse, it hits a raindrop, and the frequency change of the returning signal tells the computer whether that drop is moving toward or away from the station. For Rochesterians, this data is vital for tracking the rotation in summer thunderstorms or the intensity of a winter "lake effect" band. But since the beam is so high by the time it gets here, we’re often missing the "bottom" of the storm.

💡 You might also like: The 24-Hour Myth: Why How Many Hours in a Day Isn't Actually a Fixed Number

Why Lake Ontario Messes Everything Up

Lake Ontario is a giant heat battery. Even in January, the water is usually significantly warmer than the air blowing over it from Canada. This creates a hyper-local weather engine that drives Rochester's infamous unpredictability.

When cold air hits that warm water, it picks up moisture and rises fast. This forms narrow, intense bands of snow. Because these bands are shallow—often topping out at 5,000 or 7,000 feet—the KBUF radar and the KTYX radar (located at Montague in the Tug Hill region) sometimes struggle to see the true intensity of the core.

The "Overshooting" Effect

If the radar beam is at 6,000 feet and the heaviest snow is at 2,000 feet, the radar "sees" nothing. Or, it sees "light" returns when the ground reality is a whiteout. To compensate, meteorologists at WHEC, WROC, and WHAM often have to look at secondary sources like the TDWR (Terminal Doppler Weather Radar). There is a TDWR unit specifically for the Frederick Douglass - Greater Rochester International Airport (ROC).

However, TDWR has its own issues. It uses a shorter wavelength (C-band vs. the S-band used by NEXRAD). This means it's great at detecting wind shear for airplanes, but the signal "attenuates" or fades out if it has to look through a very heavy wall of rain. It’s like trying to see through a flashlight in a fog—the light just bounces back at you.

Reading the Map Like a Pro

When you're checking the Doppler radar in Rochester, you've gotta look for the "bright banding." This is a phenomenon where falling snow begins to melt as it hits a warmer layer of air. Melting snowflakes are coated in a thin film of water. To a radar, a wet snowflake looks like a massive, solid bowling ball of water. This makes the radar return look much more intense than it actually is. You see deep reds and purples on the map, but on the ground, it’s just a moderate, slushy mix.

- Base Reflectivity: This shows the intensity of precipitation.

- Base Velocity: This is the "Doppler" part. It shows wind speed and direction. If you see bright green next to bright red, that’s rotation. That’s when you head to the basement.

- Correlation Coefficient: This is a newer tool. It tells the meteorologist if the "stuff" in the air is the same shape. If it’s all the same, it’s rain or snow. If the shapes are all different, the radar has picked up debris—meaning a tornado has likely touched down.

The Future of Rochester’s Eye in the Sky

There has been talk for years about adding more "gap filler" radars. These are smaller, low-power units that could fill in the data holes left by the curvature of the earth. Until that happens, the best way to stay safe in Rochester is to look at a "mosaic" view. Don't just look at one station. Professional weather geeks in the area often toggle between Buffalo (KBUF), Binghamton (KBGM), and Montague (KTYX) to get a 3D mental image of what’s actually happening over the Genesee River.

Honestly, even with all the tech, the lake is always going to win. The "Rochester shadow" or the "lake-effect boom" are part of the local DNA. Technology like Dual-Polarization (Dual-Pol), which was added to the NEXRAD network about a decade ago, helps a lot. It sends out both horizontal and vertical pulses, allowing the system to figure out if it’s looking at a flat raindrop, a round hailstone, or a jagged snowflake. This has drastically improved the accuracy of rain-to-snow transitions, which is the hardest thing to predict in Western New York.

Actionable Steps for Local Weather Tracking

Stop relying on the generic weather app that came pre-installed on your phone. Those apps often use smoothed-out data models that aren't real-time Doppler.

- Use the NWS Enhanced Data Display: Go to the National Weather Service website for Buffalo. It gives you the raw, uncompressed radar feed without the "pretty" smoothing filters that can hide dangerous trends.

- Check the TDWR for ROC Airport: If it’s a high-impact wind event or a sudden summer storm, the airport radar (found on sites like RadarScope) provides much higher resolution for the immediate Rochester metro area.

- Monitor Surface Observations: Compare the radar to what the "METAR" stations are reporting at the airport. If the radar looks clear but the airport is reporting "SN" (snow), you know the radar is overshooting.

- Look for the "Hook": In the summer, if you see a hook-shaped appendage on the southwest side of a storm cell moving through towns like Chili or Henrietta, that’s a classic signature of a rotating thunderstorm.

Understanding the limitations of Doppler radar in Rochester makes you a more informed citizen. You stop blaming the "weatherman" for "getting it wrong" when you realize they are essentially trying to look at a 3D world through a 2D straw from 60 miles away. Next time a lake-effect band parks itself over Irondequoit, you’ll know exactly why the radar beam is struggling to catch the full picture.