Weather in the Northeast is a chaotic mess. Honestly, if you live between D.C. and Maine, you know the drill: one minute it’s sunny, and the next, a "bomb cyclone" is ripping your patio furniture into the neighbor's yard. It’s wild. But have you ever stopped to think about the literal billion-dollar infrastructure keeping you from getting caught in a flash flood or a surprise microburst? I’m talking about Doppler radar Northeast United States—a massive, invisible net of microwave pulses that is constantly scanning the sky to make sure we don’t die. It’s not just a colorful map on your phone. It’s a sophisticated, aging, and occasionally brilliant feat of engineering.

How the Magic Actually Happens (Basically)

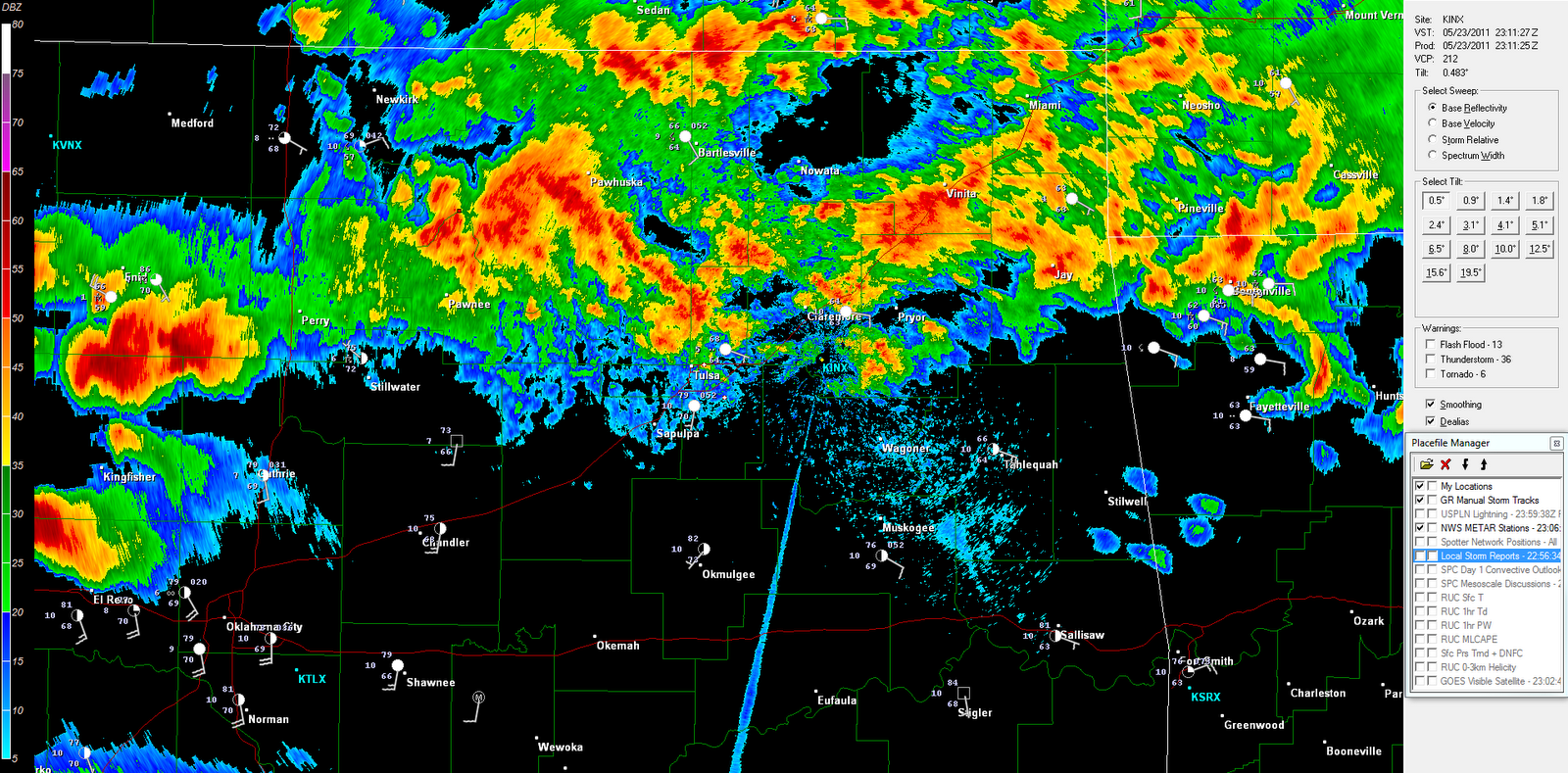

Most people think radar just "sees" rain. It’s way more intense than that. Doppler radar works by sending out a pulse and measuring how the frequency changes when it bounces off something moving. Think of a police siren. As it gets closer, the pitch goes up. As it moves away, it drops.

Meteorologists use this "Doppler shift" to see if raindrops or snowflakes are moving toward or away from the station. In the Northeast, where we get weird coastal storms and high-velocity wind events, this is the difference between a "cloudy day" and a "get in the basement now" alert.

The NEXRAD Backbone: Our Aging Guardians

The system we use is called NEXRAD (Next-Generation Radar). It’s a network of 160 high-resolution S-band Doppler radars. In our neck of the woods, these are the heavy hitters. You’ve got KOKX on Long Island, KBOX in Taunton (covering Boston), and KDIX in Mount Holly, New Jersey. These things are huge. We’re talking about massive white spheres—called radomes—that look like giant golf balls on stilts. Inside, a dish is spinning constantly, scanning the horizon at different angles.

But here’s the thing: NEXRAD isn't new. The current WSR-88D models were mostly installed in the 1990s. Sure, they’ve had massive upgrades, like Dual-Polarization (Dual-Pol) technology. Dual-Pol was a game-changer because it allows the radar to send out both horizontal and vertical pulses. Why does that matter? Because it lets meteorologists tell the difference between a fat raindrop, a jagged hailstone, and a piece of debris from someone's roof. In 2026, we take this for granted, but twenty years ago, we were basically guessing.

The "Northeast Problem": Hills, Buildings, and the Curvature of the Earth

The Northeast is a nightmare for radar coverage. Why? Geography.

First, you have the Appalachian Mountains. Radar beams travel in a straight line, but the Earth curves. If you’re too far from a station, the beam might be 10,000 feet in the air by the time it reaches your town. It’s overshoot. You might have a massive snow squall happening at ground level, but the Doppler radar Northeast United States network is looking right over the top of it. This is why places like northwestern Pennsylvania or parts of the Adirondacks can sometimes feel like "radar holes."

Then there’s the "bright band" effect. This happens when snow starts melting as it falls. To the radar, a melting snowflake looks like a giant, super-reflective raindrop. The computer screams "EXTREME RAIN!" when, in reality, it’s just a slushy mess. Local NWS offices in New York and Philly have to manually adjust for this all the time. It’s a constant battle of man vs. machine.

✨ Don't miss: The Milwaukee M18 Miter Saw 12 Inch: What Most People Get Wrong About Cordless Power

The Evolution of the 2020s: Phased Array and Beyond

We’re currently in a weird transition period. The FAA and NOAA have been looking at Phased Array Radar (PAR). Unlike the spinning dishes of the WSR-88D, PAR uses a flat panel with thousands of tiny antennas. It doesn't need to spin. It can scan the entire sky in seconds rather than minutes.

In a fast-moving Northeast environment—where a thunderstorm can turn into a localized tornado in three minutes—waiting five minutes for a full NEXRAD scan is an eternity. We need data now. While full deployment is still a ways off, the research being done at places like the National Severe Storms Laboratory is trickling down to the software updates we see in our regional centers.

Why "Wind Farms" Are the Secret Enemy of Your Weather App

Here’s a weird detail most people miss: green energy is actually making radar harder. As we build more wind farms across the hills of New York and off the coast of Jersey, those spinning blades create "clutter." To a Doppler radar, a 300-foot spinning blade looks a lot like a rotating thunderstorm.

Meteorologists call this "wind farm interference." Engineers have to write complex algorithms to filter out the turbines so your weather app doesn't show a random "tornado" in the middle of a wind farm. It’s a fascinating conflict between our need for clean energy and our need for accurate storm tracking.

The Real Impact: The 2021 Ida Disaster

If you want to know why we invest so much in Doppler radar Northeast United States, look at what happened during the remnants of Hurricane Ida. The storm moved into the Northeast and dropped a "firehose" of rain. The radar at Mount Holly (KDIX) was the only thing providing real-time data on the Tornadic Debris Signatures (TDS).

A TDS is when the radar picks up non-meteorological objects—stuff like wood, insulation, and dirt—being lofted into the air. When a meteorologist sees a "debris ball" on the screen, they don't wait for a visual confirmation. They issue the warning immediately. That tech saved lives in Jersey and PA that night.

Practical Advice for Using Radar Data

Stop just looking at the "standard" map on your phone. Most of those apps use smoothed-out data that hides the raw details.

💡 You might also like: How to Download Videos From Facebook Messenger Without Losing Your Mind

- Get a Pro-Level App: Use something like RadarScope or GRLevel3. These apps give you access to the "Level II" data. You can see the actual velocity (wind speed) and the correlation coefficient (which helps identify debris).

- Understand Base vs. Composite: "Base Reflectivity" is just the lowest tilt of the radar. It shows what’s happening near the ground. "Composite Reflectivity" shows the strongest echoes at any height. If you want to know if it's raining on you, use Base.

- Check the Timestamp: This is huge. Sometimes your phone caches an old image. If the timestamp is more than 6-10 minutes old, you're looking at the past. In a fast-moving Northeast squall line, that's dangerous.

- Learn the "Hook": If you see a hook-shaped echo on the southwest side of a storm cell, that’s rotation. In the Northeast, these are often "rain-wrapped," meaning you can't see the tornado with your eyes. Trust the Doppler.

Looking Ahead

The future of weather tracking in the Northeast isn't just bigger radars; it's smaller ones. We are seeing a move toward "gap-filling" X-band radars. These are smaller, cheaper units that cover the blind spots under the main NEXRAD beams. Urban areas like New York City are starting to utilize these to manage flash flooding in subways and basements more effectively.

Technology won't stop the storms from coming. The Atlantic is getting warmer, and the atmospheric "rivers" hitting the Northeast are getting wider. But as long as we keep the Doppler network humming, we at least have a fighting chance to get out of the way.

To stay truly prepared, monitor the National Weather Service (NWS) regional offices directly. Offices like NWS New York (Upton), NWS Boston (Norton), and NWS Philadelphia (Mount Holly) provide technical discussions that go way deeper than a simple sun-and-cloud icon. Learning to read their radar-based "Area Forecast Discussions" is the single best way to stay ahead of the next big Northeast weather event.