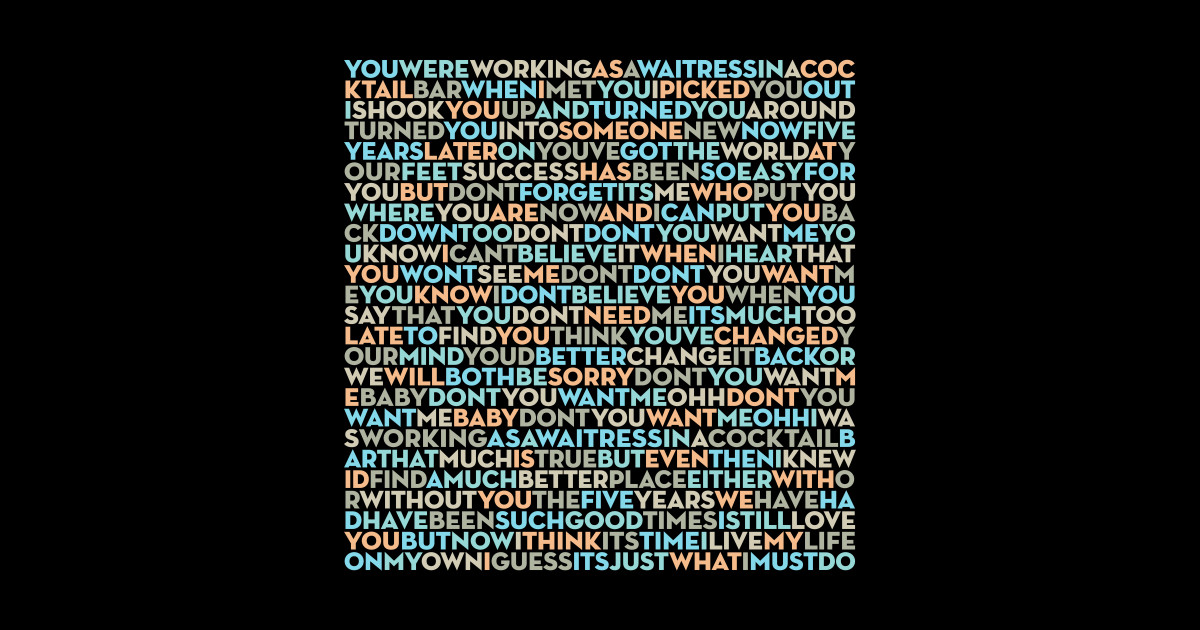

You know the synth line. That jagged, icy hook that feels like 1981 distilled into a single sequence of notes. It's the ultimate karaoke song, the one where the guys wait for the first verse and the girls take the second. But if you actually sit down and read don't you want me the human league lyrics, the vibe shifts from catchy synth-pop to something way more uncomfortable. It’s not really a love song. It’s a power struggle.

Philip Oakey, the frontman with the legendary asymmetrical haircut, didn’t even want this track on the album Dare. He thought it was too poppy, too lightweight compared to the band’s darker, more experimental roots. He famously fought to keep it from being the fourth single. He lost that fight, and the song became a global monster. But the lyrics he wrote—and the way Susan Ann Sulley responds in the second verse—tell a story of obsession, gaslighting, and the toxic reality of "making" someone famous.

The Narrative Trap in Don’t You Want Me the Human League Lyrics

The song starts with a classic Pygmalion setup. Oakey’s character is the svengali, the man with the plan. He meets a girl working in a cocktail bar. He "picks her up," shakes her out, and turns her into something new. There’s a massive sense of ownership in the opening lines. When he sings about how she was working as a waitress when he met her, he isn't reminiscing; he’s asserting a debt.

It’s about status. He’s reminding her that she was "nothing" before him. This is where the don't you want me the human league lyrics get gritty. He’s not saying "I love you." He’s saying "I made you, and you owe me your life." The repetition of "Don't, don't you want me?" isn't a plea for affection. It’s a demand for recognition. He’s losing his grip on his creation, and he’s terrified.

Then the perspective flips. This was the genius move.

Susan Ann Sulley enters. She’s not the passive project Oakey describes. She acknowledges the past—yeah, she was a waitress, big deal—but she’s moved on. She’s found her own feet. When she sings "I'll find a much better life, with or without you," she’s shattering the illusion of his control. It’s one of the first times in 80s pop where the "subject" of a song gets to talk back and dismantle the narrator's ego in real-time.

That Cocktail Bar and the Reality of 1981 Sheffield

The cocktail bar isn't just a random setting. In the early 80s, the "cocktail bar" was a symbol of aspirational glamour in a Britain that was otherwise struggling through industrial decline. For a girl in Sheffield to be "plucked" from that environment and turned into a star was a very real Cinderella narrative that the media loved.

👉 See also: The Real Story Behind I Can Do Bad All by Myself: From Stage to Screen

But Oakey was inspired by something much more mundane: a photo story in a teen girl's magazine. He saw a series of panels about a relationship breaking down and swiped the basic plot. It’s funny how such a massive cultural touchstone started from a cheap magazine layout. It gives the song that "everyman" feel despite the high-concept electronic production.

Interestingly, the vocal delivery is intentionally flat. Oakey and Sulley aren't belting these lines out like soul singers. They’re conversational. Almost bored. Or maybe just exhausted by each other. That coldness is what makes the don't you want me the human league lyrics stick. They feel like a real argument overheard through a thin apartment wall.

Why the Song Nearly Never Happened

The Human League was in a weird spot. The original lineup had split, with Martyn Ware and Ian Craig Marsh leaving to form Heaven 17. Oakey was left with the name and a mountain of debt. He famously recruited Susan Ann Sulley and Joanne Catherall from a dance floor at the Crazy Daisy Nightclub in Sheffield. They weren't professional singers. They were teenagers who looked cool.

That lack of "professional" polish is exactly why the song works. When Sulley sings her rebuttal, she sounds like a real person, not a session musician. She sounds like someone who actually lived through the five years of growth she’s claiming. If she had been a powerhouse vocalist, the vulnerability and the defiance would have felt performative. Instead, it feels honest.

Producer Martin Rushent was the one who saw the potential that Oakey missed. Rushent spent ages tweaking the Linn LM-1 drum machine and the Roland Jupiter-4 synths to get that specific, punchy sound. He knew that the contrast between the upbeat, danceable music and the bitter, resentful lyrics would be gold. He was right. It stayed at number one in the UK for five weeks and topped the Billboard Hot 100 in the US.

Decoding the Power Dynamics

Let's look at the bridge. "It's much too late to find, you think you've changed your mind."

✨ Don't miss: Love Island UK Who Is Still Together: The Reality of Romance After the Villa

He’s gaslighting her. He’s telling her that her feelings aren't real, that she’s just confused. This is the dark heart of the track. Most people dance to it without realizing they’re participating in a scene of emotional manipulation. The guy is spiraling. He sees her success as a direct result of his "investment," and he can't handle the fact that she’s an independent entity now.

- The Claim: I found you in a bar, I changed your life.

- The Threat: You'll be back in that bar if you leave me.

- The Reality: She’s doing fine and doesn't need him.

It’s a classic breakup dynamic played out on a grand, electronic stage. People often compare it to Gotye’s "Somebody That I Used to Know," and the comparison holds up. Both songs use a "he said/she said" structure to show how two people can experience the exact same relationship in completely different ways. In his version, he’s a savior. In her version, he was a stepping stone she’s grateful to have left behind.

The Cultural Legacy of the Lyrics

Even decades later, these lyrics resonate because the "Svengali" trope hasn't gone away. We see it in the music industry constantly—older producers "discovering" young female talent and then feeling entitled to their personal lives. The Human League managed to critique this dynamic while being right in the middle of it.

The music video helped cement this. Directed by Steve Barron, it’s a "film within a film." It shows the band on a movie set, further blurring the lines between reality and performance. It emphasizes the idea that the "waitress" was just a role she was playing for him, and now she’s ready to play a different character.

Honestly, the song wouldn't have worked if it was just Oakey singing. It needed the female voice to provide the reality check. Without Sulley, it’s just a song about a bitter guy. With her, it’s a cinematic drama.

What You Can Learn From the Song Today

If you’re a songwriter or just someone who loves pop culture, there’s a massive lesson in how don't you want me the human league lyrics are constructed.

🔗 Read more: Gwendoline Butler Dead in a Row: Why This 1957 Mystery Still Packs a Punch

- Conflict is everything. Don't just write about being in love. Write about two people who disagree about whether they were ever in love at all.

- Specific details matter. The mention of the cocktail bar makes the world of the song feel lived-in. It gives the listener a visual to latched onto.

- Subvert the melody. If you have a bright, poppy melody, try putting dark, cynical lyrics over it. The friction creates something memorable.

The Technical Side of the Sound

While the lyrics do the heavy lifting emotionally, we can't ignore how the sound influenced the perception of the words. The use of the Korg 770 and the Micro-Composer gave the track a rigid, almost robotic feel. This mirrors the "stiff" emotional state of the male narrator. He’s trying to be clinical and controlling, but the cracks are showing.

By the time the final chorus hits, the "Don't you want me?" becomes a desperate loop. It’s no longer a question; it’s a malfunction. He’s stuck in his own head, unable to process that the "waitress" has left the building.

Moving Forward With This Classic

Next time you hear this at a wedding or a 80s night, pay attention to that second verse. Listen to the way Sulley’s voice cuts through Oakey’s bravado. It’s a masterclass in songwriting that refuses to give the listener a happy ending.

To really appreciate the depth here, you should:

- Listen to the "Extended Dance Mix" to hear how the instrumental builds the tension before the lyrics even start.

- Compare it to "Mirror Man," another Human League track that deals with narcissism and image.

- Read Philip Oakey’s later interviews where he admits he was wrong about the song’s potential.

The track remains a staple not just because it's catchy, but because it captures a very human, very ugly truth about how we try to own the people we claim to love. It’s a four-minute lesson in boundaries, or the lack thereof.

If you're looking to dive deeper into 80s synth-pop narratives, check out the lyrics to Soft Cell’s "Say Hello, Wave Goodbye" or Eurythmics’ "Love Is a Stranger." They inhabit that same neighborhood of polished surfaces and messy interiors.

To get the most out of your 80s playlist, try listening to the album Dare in its entirety. It’s a perfect snapshot of a moment when technology and raw human emotion collided in a way that changed pop music forever. You'll see that "Don't You Want Me" isn't an outlier—it's the peak of a very specific, very cynical kind of genius.