Most people remember the 90s for the console wars. You had the Super Nintendo and the Sega Genesis duking it out with 16-bit graphics that, at the time, felt like peak technology. But tucked away in the pockets of millions of kids was the original Game Boy—a monochrome, four-shade-of-pea-soup handheld that technically shouldn't have been able to handle what Rare was cooking up. When the donkey kong land games first hit the scene, they weren't just simple ports. They were an audacious, slightly buggy, and visually mind-blowing attempt to cram the "impossible" SGI pre-rendered graphics of the SNES into a device powered by four AA batteries.

It worked. Mostly.

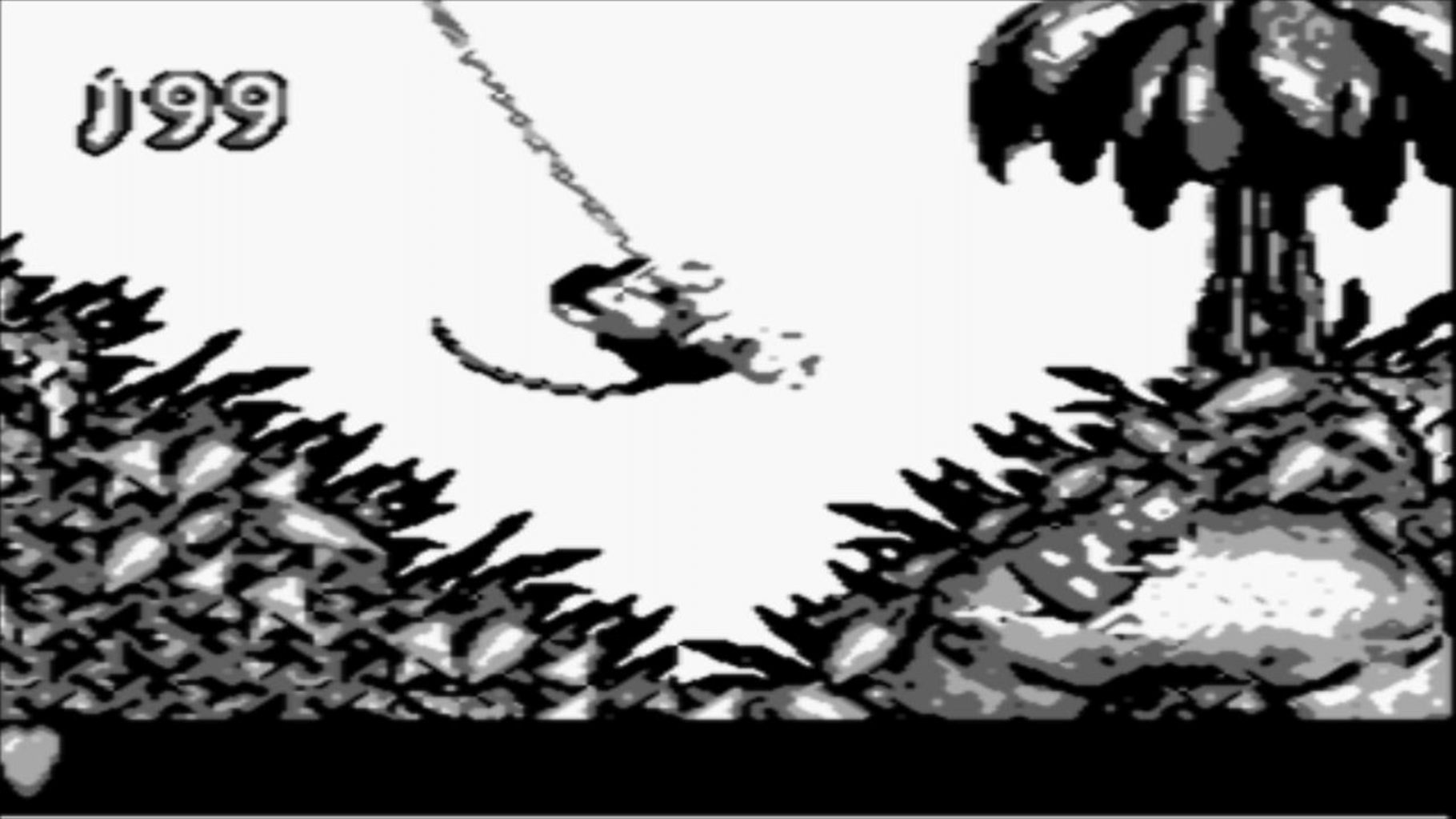

Honestly, playing these games today is a trip. If you go back and fire up the first Donkey Kong Land (1995), your eyes have to adjust. It’s dense. Rare decided to use the same high-fidelity 3D modeling techniques they used for Donkey Kong Country, but translating those complex textures to a 160x144 resolution screen without a backlight was a bold choice. It created this weird, gritty aesthetic that separates these titles from anything else on the system. They feel heavier than Super Mario Land. They feel darker.

The Cranky Kong Bet: Why These Games Exist

The lore behind the first game is actually meta-commentary on the industry itself. Cranky Kong, ever the bitter veteran, makes a bet with Donkey and Diddy. He claims the only reason their 16-bit adventure was a success was because of the "fancy graphics" and sound of the SNES. He bets them they couldn't cut it on an 8-bit handheld.

This isn't just a manual backstory; it’s a direct challenge to the player.

Because of this "bet," the developers didn't just port the levels from the home console. They built entirely new stages. In the first Donkey Kong Land, you aren't just retreading the jungle. You’re navigating "Big Ape City," a concrete jungle that felt like a precursor to the urban levels in Donkey Kong 64 or even Super Mario Odyssey. It’s a distinct vibe. The music, composed by David Wise and Graeme Norgate, is some of the most complex audio ever squeezed out of the Game Boy’s sound chip. It’s got that signature "wet" and atmospheric jungle sound, even through those tinny speakers.

💡 You might also like: Why the Clair Obscur: Expedition 33 Boss Fights Feel So Different

Squished Kongs and Motion Blur

Let’s talk about the technical elephant in the room. Or the gorilla.

The donkey kong land games pushed the Game Boy so hard that they sometimes broke it. On an original DMG-01 (the grey brick), the ghosting was real. Move too fast, and Donkey Kong became a blurry smudge against a background that was already trying to do too much. Rare used a technique called "interlacing" to simulate more shades of grey, but it meant that if you weren't playing under a direct halogen lamp, you were basically guessing where the pits were.

Donkey Kong Land 2 (1996) changed the approach. It was much closer to a direct translation of Diddy’s Kong Quest. You lost the unique city environments, but you gained better readability. The sprites were tweaked. The backgrounds were slightly less cluttered. It’s objectively a "better" game, but it lacks some of the experimental weirdness that made the first one so memorable.

Then came Donkey Kong Land III in 1997. By this point, the Game Boy was aging, and the Game Boy Color was on the horizon. In Japan, this game actually got a full GBC release (Donkey Kong GB: Dinky Kong & Dixie Kong), but in the West, we got the monochromatic version. It’s arguably the most polished of the trio. It features the "Lost World" and a time-attack mode that gave it way more replay value than your average handheld platformer.

The Weirdness of the Yellow Cartridge

If you grew up in this era, you remember the cartridges. While most Game Boy games were grey (or black for "dual-mode" games), the first Donkey Kong Land came in a bright, banana-yellow shell. It was a marketing masterstroke. It stood out in your carrying case like a beacon of 16-bit rebellion.

📖 Related: Hollywood Casino Bangor: Why This Maine Gaming Hub is Changing

But there's a specific nuance to the physics in these games that most modern retrospectives miss. The jump arc is different from the SNES versions. It's floatier. Because the screen real estate is so small, the developers had to adjust how high and far the Kongs could move. If they’d kept the SNES physics, you would have been jumping into "blind" hazards constantly. Even with these adjustments, the DKL trilogy is notoriously difficult. The hitboxes are... let's call them "ambitious."

Why They Haven't Been Forgotten

You might think these games are obsolete because of the Game Boy Advance ports or the Virtual Console. But there is a specific charm to the 8-bit limitations. It’s the same reason people still listen to lo-fi music. There is a "crunch" to the sound and a "fuzz" to the visuals that creates a unique atmosphere.

Take the boss fights. Fighting Very Gnawty in the first Land game feels claustrophobic in a way the SNES version never did. The screen feels like it’s closing in on you. It turns a standard platformer into a weirdly tense survival experience.

A Quick Breakdown of the Trilogy’s Identity:

- Donkey Kong Land (1995): Entirely new levels, Big Ape City, experimental graphics, peak 90s attitude.

- Donkey Kong Land 2 (1996): Better performance, mirrors the SNES sequel closely, introduces Dixie Kong to the handheld world.

- Donkey Kong Land III (1997): Massive world map, refined gameplay, technically the most stable, features Kiddy Kong (for better or worse).

Is it perfect? No. The lack of a save battery in some early versions (relying on passwords) was a nightmare. The "save" system in DKL1 required you to collect K-O-N-G tokens, which meant you couldn't just stop whenever you wanted. It was brutal.

The Modern Way to Experience the Series

If you’re looking to dive back into the donkey kong land games today, don’t just grab an original Game Boy and a flashlight. It’s a recipe for a headache.

👉 See also: Why the GTA Vice City Hotel Room Still Feels Like Home Twenty Years Later

The best way to play them is on a Super Game Boy or through the Nintendo Switch Online service. When played on a Super Game Boy (the SNES peripheral), the first DKL actually has a custom border and a limited color palette that makes the sprites pop. It’s how the game was meant to be seen. You can actually distinguish the bananas from the background.

There's also a massive ROM hacking community that has "colorized" these games. They’ve taken the original 8-bit code and applied full Game Boy Color palettes to them, making them look like lost GBC masterpieces. It’s a testament to the quality of the underlying game that people are still spent hundreds of hours "fixing" games that are three decades old.

Final Verdict: Are They Actually Good?

People often ask if these are "good" games or just "good for the Game Boy."

It’s a bit of both. If you go in expecting the buttery smooth 60fps movement of a modern indie platformer, you’re going to be frustrated. These games are slow. They are methodical. You have to learn the rhythm of the screen scrolling.

But as a feat of engineering? They are incredible. Rare pushed the Z80 processor to its absolute limit. They proved that "pre-rendered 3D" wasn't just a gimmick for powerful consoles, but a stylistic choice that could define an entire era of handheld gaming. The donkey kong land games represent a time when developers weren't afraid to make something look a little "ugly" if it meant being groundbreaking.

Your Next Steps for DK Discovery

If you’re ready to revisit the banana-yellow cartridge era, here is exactly how to do it without the 1995 frustrations:

- Check Nintendo Switch Online: All three games are currently available in the Game Boy library for "Expansion Pack" subscribers. It includes "suspend points," which fixes the brutal password/save system issues.

- Look for the Colorized Hacks: If you enjoy emulation, search for the "Donkey Kong Land Color" patches by fan developers like Marc Max. It transforms the experience into something that looks native to the Game Boy Color.

- Compare the Soundtracks: Pull up the DKL1 soundtrack on YouTube and listen to "skyline shimmy." It’s a masterclass in 8-bit composition that stands up against the SNES originals.

- Start with DKL2: If you find the first game too visually cluttered, start with the second. It’s the most accessible entry point for a modern player.