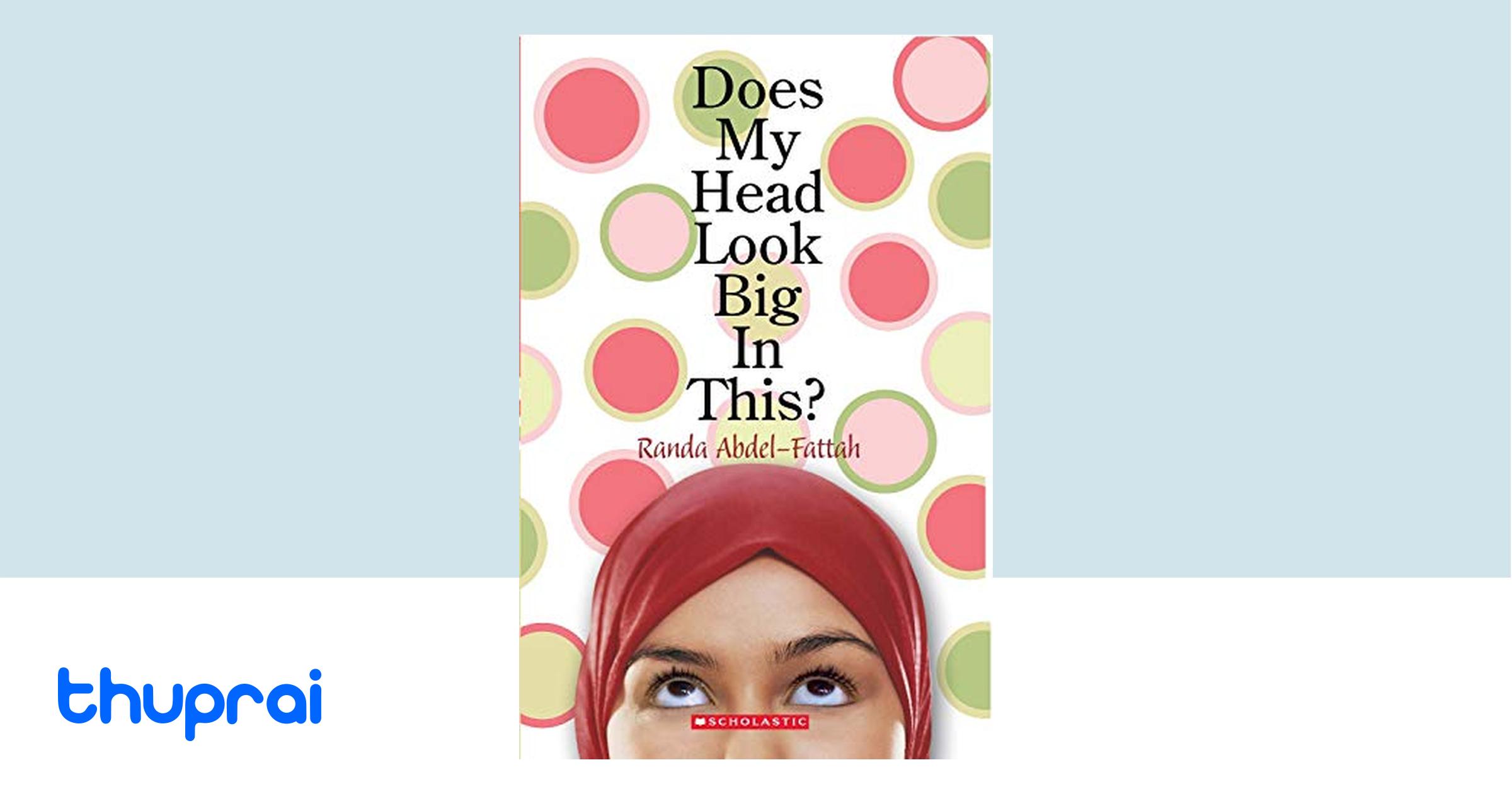

It was 2005. Before TikTok trends and Instagram filters dictated how we saw ourselves, a 16-year-old girl named Amal Abdel-Hakim walked into our lives. She was sharp, funny, and navigating the absolute minefield of an Australian suburban high school while wearing a hijab. Randa Abdel-Fattah’s debut novel, Does My Head Look Big in This?, didn't just land on the shelves; it cracked something open in the YA world that hadn't been seen before. It was loud. It was unapologetic. Honestly, it was the first time a lot of readers—both Muslim and not—saw the "headscarf" as something other than a political statement or a symbol of oppression. It was just a part of Amal’s outfit.

But here's the thing.

The book is almost two decades old now, yet it still feels weirdly relevant. You’d think by 2026 we’d have moved past some of these conversations, but the "full-timer" struggle Amal faces—the decision to wear the hijab permanently—is a journey that thousands of young women still navigate every single day. It’s a story about identity, sure, but it's mostly about the guts it takes to be yourself when everyone else is trying to categorize you.

The Reality of Being a Full-Timer

Amal isn't a saint. That’s probably the best part of the book. She’s obsessed with Sex and the City (which, yeah, dates the book a bit, but the vibe remains), she worries about her weight, and she has a massive crush on a guy named Adam who isn't Muslim. When she decides to wear the hijab full-time, she isn't doing it because her parents forced her. In fact, they’re actually a bit worried about the backlash she’ll face.

She does it because she wants to see if she can live up to her own values.

✨ Don't miss: Why Pics of Short Haircuts Often Fail You at the Salon

Abdel-Fattah captures that specific brand of teenage anxiety so perfectly. It’s that "everyone is looking at me" feeling, but dialed up to eleven because you’ve added a visible religious marker to your uniform. The book dismantles the "oppressed Muslim woman" trope by showing that the struggle isn't the scarf itself. The struggle is the people looking at the scarf. It’s the snide comments from classmates like Tia Tamos, the "random" security checks, and the patronizing "oh, you’re so brave" comments from people who don't actually get it.

Why Representation Actually Matters (Not Just as a Buzzword)

We talk about representation a lot lately. It’s become a bit of a corporate checkbox. But back when Does My Head Look Big in This? was released, finding a Muslim protagonist who was funny, flawed, and obsessed with pop culture was like finding water in a desert.

The book tackled the "clash of civilizations" narrative by basically laughing at it. Amal is Australian. She loves meat pies. She speaks with a thick Aussie accent. She also happens to pray five times a day. By grounding the story in the mundane—school lunches, shopping trips, and family dinners—Abdel-Fattah humanized a demographic that, at the time, was being demonized in the post-9/11 media cycle.

The Adam Factor

Let’s talk about Adam. Every YA novel needs a love interest, but Adam serves a specific purpose here. He’s the "forbidden fruit," but not in a cheesy way. Their chemistry is real. It’s awkward. It’s painful. Amal’s crush on him forces her to confront the boundaries of her faith versus her feelings. It asks a question that many religious teens face: How do you maintain your identity while still wanting to fit in with the "normal" world?

The resolution isn't a fairy tale. It’s messy. It’s human.

The Cultural Impact and the "Aussie-Muslim" Voice

Randa Abdel-Fattah, who is now an academic and a prominent advocate for Palestinian rights, didn't just write a book; she launched a sub-genre of Australian literature. Before this, the Australian literary canon was... well, it was very white. Very "outback." Very "bush poetry."

Does My Head Look Big in This? brought the suburbs into the light. It showed the complex tapestry of Melbourne and Sydney life—the Greek neighbors, the Lebanese bakeries, the tension between the "old country" and the new home.

What People Often Get Wrong

There's a common misconception that this book is only for Muslim girls. That’s a mistake. If you strip away the religious context, it’s a story about a kid trying to be different in a world that demands conformity. It’s for anyone who has ever worn something weird to school, had a "weird" lunch, or felt like their family was just a bit too loud.

It’s also surprisingly educational without being a textbook. You learn about wudu, the importance of Ramadan, and the nuances of hijab vs. niqab, but it’s all woven into the plot. You're learning because you're worried about whether Amal is going to get through her history presentation, not because the author is lecturing you.

Facing the Backlash

It wasn't all praise. The book has been challenged in schools. It’s been caught in the crosshairs of "culture wars." Critics have sometimes accused it of being too "pro-Islam" or, conversely, not "conservative enough."

👉 See also: Tory Burch Black Belt: Why It's Still the Best Investment You’ll Make for Your Closet

But that’s exactly why it works.

If a book makes everyone a little bit uncomfortable, it’s usually because it’s hitting on a truth that people aren't ready to talk about. Abdel-Fattah doesn't shy away from the Islamophobia that ramped up in Australia during the mid-2000s. She portrays the "Cronulla Riots" era tension with a sharpness that still stings.

How to Approach the Book Today

If you’re picking this up for the first time in 2026, or maybe re-reading it for a nostalgia hit, here is how to get the most out of it:

- Look past the tech: Ignore the lack of iPhones. Focus on the internal monologue. The "am I enough?" question hasn't changed, even if the apps have.

- Notice the side characters: Mrs. Vaselli, the elderly Greek neighbor, has one of the best character arcs in the book. Her relationship with Amal is a masterclass in how shared trauma and shared humanity can bridge huge cultural gaps.

- Acknowledge the humor: This is a funny book. Amal’s internal voice is snarky and self-deprecating. If you aren't laughing at her descriptions of her extended family, you're missing the point.

- Think about the "Second Generation" experience: The tension between Amal and her parents is different than the tension between her parents and their parents. It’s a specific look at the children of immigrants trying to build a third identity that belongs to neither world completely.

Moving Forward with Amal’s Guts

The legacy of Does My Head Look Big in This? isn't just a spot on a high school curriculum. It’s the fact that it gave permission to a generation of writers to tell their stories without explaining themselves to a "mainstream" audience first.

If you’re struggling with your own identity—whether it involves a hijab, a career change, or just standing up for a belief that isn't popular—take a page out of Amal’s book. Put the "scarf" on. Face the music. You’ll realize pretty quickly that the people who mind don't matter, and the people who matter don't mind.

To truly understand the weight of this story, look into the actual history of the Cronulla Riots in Australia to see the environment in which this book was written. Read Abdel-Fattah’s later work, like The Lines We Cross, to see how her political and social commentary has evolved. Most importantly, stop worrying about whether your "head looks big" in whatever you’re choosing to carry. Just wear it.

Actionable Next Steps

- Read the 10th Anniversary Edition: It includes a fantastic introduction that contextualizes the book’s impact on the global literary scene.

- Compare and Contrast: Read it alongside The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas or I Am Malala. Seeing how different cultures handle the "burden of representation" provides a much deeper understanding of modern YA.

- Support Diverse Books: Check out the "We Need Diverse Books" organization to find more titles that break the mold of traditional storytelling.

- Journal Your "Full-Timer" Moment: Write about a time you chose to do something that made you stand out, even though it was terrifying. Reflect on whether the fear came from the action itself or the projected reactions of others.