It is a weirdly hot topic. You’ve probably seen the headlines or heard politicians arguing about it during election cycles, usually with a lot of heat and not much light. People get really fired up about the idea that anyone born on U.S. soil is automatically a citizen. But have you ever actually stopped to ask, why do we have birthright citizenship in the first place? It wasn't just some random accident or a "loophole" created by bored lawyers in the 1800s.

It was a fight. A massive, bloody, transformative fight.

If you want to understand the "why," you have to look at the mess that was the post-Civil War era. Before 1868, the rules were a total disaster. The Supreme Court had basically broken the country’s legal moral compass with the Dred Scott v. Sandford decision in 1857. In that ruling, Chief Justice Roger Taney—honestly, one of the most infamous figures in legal history—claimed that Black people, whether enslaved or free, could never be citizens. It was a gatekeeping move of the highest order. It meant that even if you were born here, worked here, and lived your whole life here, you were legally a "non-person" in the eyes of the federal government.

The 14th Amendment changed everything.

👉 See also: Finding Someone in the Al Cannon Detention Center: What You Actually Need to Know

The 14th Amendment is the Real Engine Room

When the Civil War ended, the North had a massive problem. Millions of formerly enslaved people were now free, but they were in a legal limbo. Southern states were already busy passing "Black Codes" to keep them in a state of semi-slavery. To fix this, Congress didn't just pass a law—they changed the Constitution.

The Citizenship Clause is the very first sentence of the 14th Amendment. It says: "All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside."

That’s it. That’s the whole ballgame.

It was designed to be an "objective" rule. The writers, like Senator Jacob Howard and Representative John Bingham, wanted to make sure that citizenship didn't depend on the whims of a local governor or a racist judge. They wanted a rule so simple that it couldn't be argued away. If you are born here, you are one of us. Period. They were basically trying to "future-proof" equality.

What Does "Subject to the Jurisdiction" Actually Mean?

This is where the Twitter arguments usually start. Some people argue that "subject to the jurisdiction" means you have to owe total political allegiance to the U.S., which would exclude the children of undocumented immigrants or tourists.

But history doesn't really back that up.

Back in 1866, when they were debating this, the only people they really intended to exclude were the children of foreign diplomats (who have sovereign immunity) and members of Native American tribes (who were then considered citizens of their own quasi-sovereign nations). Everyone else? They were under the "jurisdiction" of U.S. laws. If you can be arrested for breaking a speed limit or committing a crime while you're here, you're under the jurisdiction.

The Case That Settled the Debate (Mostly)

If the 14th Amendment was the foundation, United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1898) was the skyscraper built on top of it.

Wong Kim Ark was born in San Francisco to Chinese parents. His parents were merchants, legally living in the U.S., but they weren't citizens because at the time, federal law literally prohibited Chinese immigrants from naturalizing. After a trip to China, Wong Kim Ark tried to come back home to California, but the government blocked him. They said he wasn't a citizen because his parents weren't citizens.

The Supreme Court disagreed.

Justice Horace Gray wrote the majority opinion. He looked back at English Common Law—the "law of the soil" or jus soli. He argued that the U.S. had always followed this tradition. The Court ruled that because Wong Kim Ark was born on U.S. soil, he was a citizen from birth. It didn't matter what his parents' status was. This case is the reason why birthright citizenship is so rock-solid today. It turned a constitutional sentence into a functional reality for millions of immigrant families.

Why This Matters for the Economy and Society

Honestly, birthright citizenship is a huge reason why the U.S. doesn't have the same kind of permanent "underclass" issues that some European countries struggle with.

In some countries, you can have families living there for three generations—speaking the language, paying taxes, never having visited their "ancestral" home—and they are still considered "foreigners" or "residents" without the right to vote. That creates a lot of social friction. It makes people feel like they don't have a stake in the society they live in.

- Integration: Birthright citizenship acts as a giant integration machine. It tells the children of immigrants, "You belong here."

- Labor Markets: It ensures that the next generation of workers is fully legal, mobile, and able to contribute to the economy without being stuck in the "shadow economy."

- Administrative Simplicity: Can you imagine the paperwork if we didn't have this? We’d need a massive federal bureaucracy just to track the lineage of every single baby born in every hospital to prove their "eligibility."

Common Misconceptions People Still Have

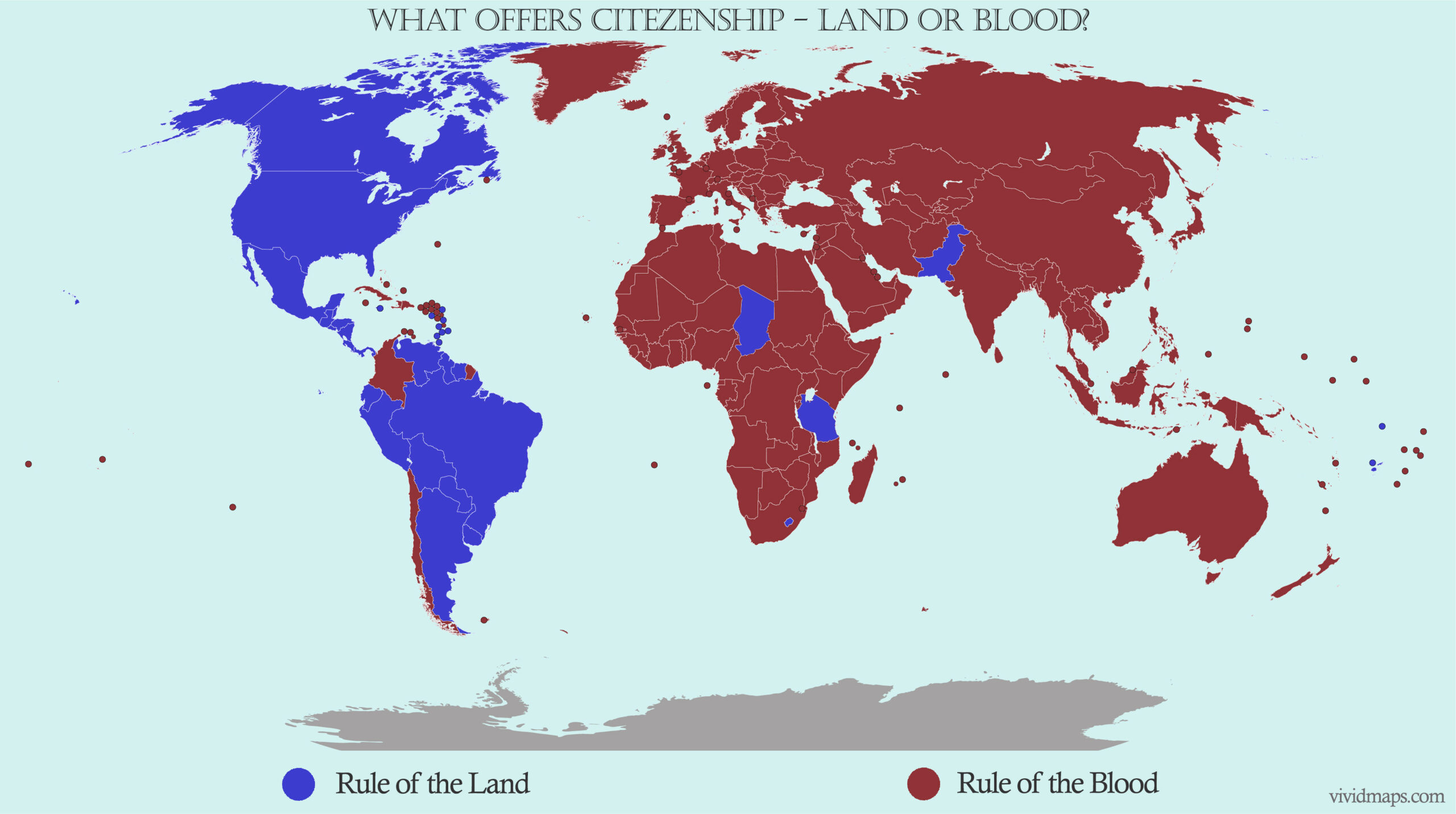

A lot of folks think the U.S. is the only country that does this. That’s not true. About 30 countries have some form of jus soli. Most of them are in the Western Hemisphere—Canada, Mexico, Brazil, Argentina. It’s a "New World" thing. Old World countries (Europe and Asia) tend to follow jus sanguinis, or "law of the blood," where your citizenship depends on your parents.

There's also the "anchor baby" myth. People talk about it like it's a magic ticket for parents to stay in the country. It’s not. A child citizen cannot sponsor their parents for a green card until they are 21 years old. That’s a 21-year wait. It’s hardly a "get out of jail free" card for immigration status.

Can a President End It With an Executive Order?

You’ll hear this every few years. A politician will claim they can just sign a paper and end birthright citizenship.

Legally speaking? Probably not.

Because birthright citizenship is baked into the 14th Amendment of the Constitution, changing it usually requires a Constitutional Amendment. That means two-thirds of both the House and Senate, plus three-quarters of the states. That is an incredibly high bar. Some conservative scholars, like John Eastman, have argued that the Supreme Court could "re-interpret" the 14th Amendment to exclude certain groups, but that would require the Court to basically overturn over 125 years of legal precedent since the Wong Kim Ark case.

The Nuance We Often Miss

We shouldn't pretend it's a perfect system without critics. There are valid debates about whether it encourages "birth tourism," where wealthy people from other countries fly here just to give birth so their kid has a U.S. passport. This definitely happens. But the question is: is that small group of people a big enough "problem" to justify tearing up a constitutional principle that provides stability for everyone else?

Most legal experts say no.

The stability of knowing exactly who is and isn't a citizen is worth the occasional edge case. It prevents "statelessness"—a horrific legal limbo where a person has no country to call home and no government to protect their rights.

What You Should Do Next

If you’re trying to wrap your head around how this affects the current legal landscape, don’t just take a politician’s word for it. The history is the key.

- Read the 14th Amendment yourself. It’s short. The first section is where the magic happens.

- Look up the history of the Civil Rights Act of 1866. It was the precursor to the 14th Amendment and gives a lot of context on what the "Founding Fathers" of that era were actually thinking.

- Check out the American Immigration Council's fact sheets. They do a great job of breaking down the actual statistics of how citizenship impacts the economy, which is often very different from the rhetoric you hear on the news.

- Follow the current court dockets. While the 14th Amendment is settled law for now, there are always lower court cases involving the "jurisdiction" clause that could eventually bubble up to the Supreme Court.

Understanding why we have birthright citizenship isn't just a history lesson; it's about understanding the core of American identity. It’s the idea that your "American-ness" isn't about who your parents were or where they came from. It's about where you stand. If you’re born on this soil, you’re part of the story. That is a powerful, radical idea that has kept the country’s legal gears turning for over 150 years.