It is a question that usually comes up in a hushed tone or a frantic Google search after seeing a news headline. Why do they do female circumcision? Most people in the West find the concept entirely alien, if not horrifying. But for over 200 million women and girls alive today, it isn't a headline. It’s a memory. Or a looming expectation.

Honestly, the term "circumcision" is a bit of a misnomer here. In medical and human rights circles, it’s almost exclusively called Female Genital Mutilation or Cutting (FGM/C). Unlike male circumcision, which is generally a simpler procedure, FGM involves the partial or total removal of external female genitalia for non-medical reasons. It’s complicated. It’s deeply rooted in history. And it’s definitely not just about "one thing."

To understand why this happens, you have to look past the surface-level shock. It isn't usually done out of malice by "villains." It’s done by mothers, grandmothers, and aunts who genuinely believe they are doing what is best for the girl's future. That’s the hardest part to wrap your head around.

The cultural engine: Why do they do female circumcision in the first place?

Social pressure is a hell of a drug. In many communities across parts of Africa, the Middle East, and Asia, FGM is a prerequisite for marriage. If a girl isn't "cut," she might be considered "unclean" or "promiscuous." This makes her unmarriageable. In a society where a woman’s economic survival depends entirely on her husband and his family, failing to perform the procedure is seen as a death sentence for her social and financial future.

It’s about belonging.

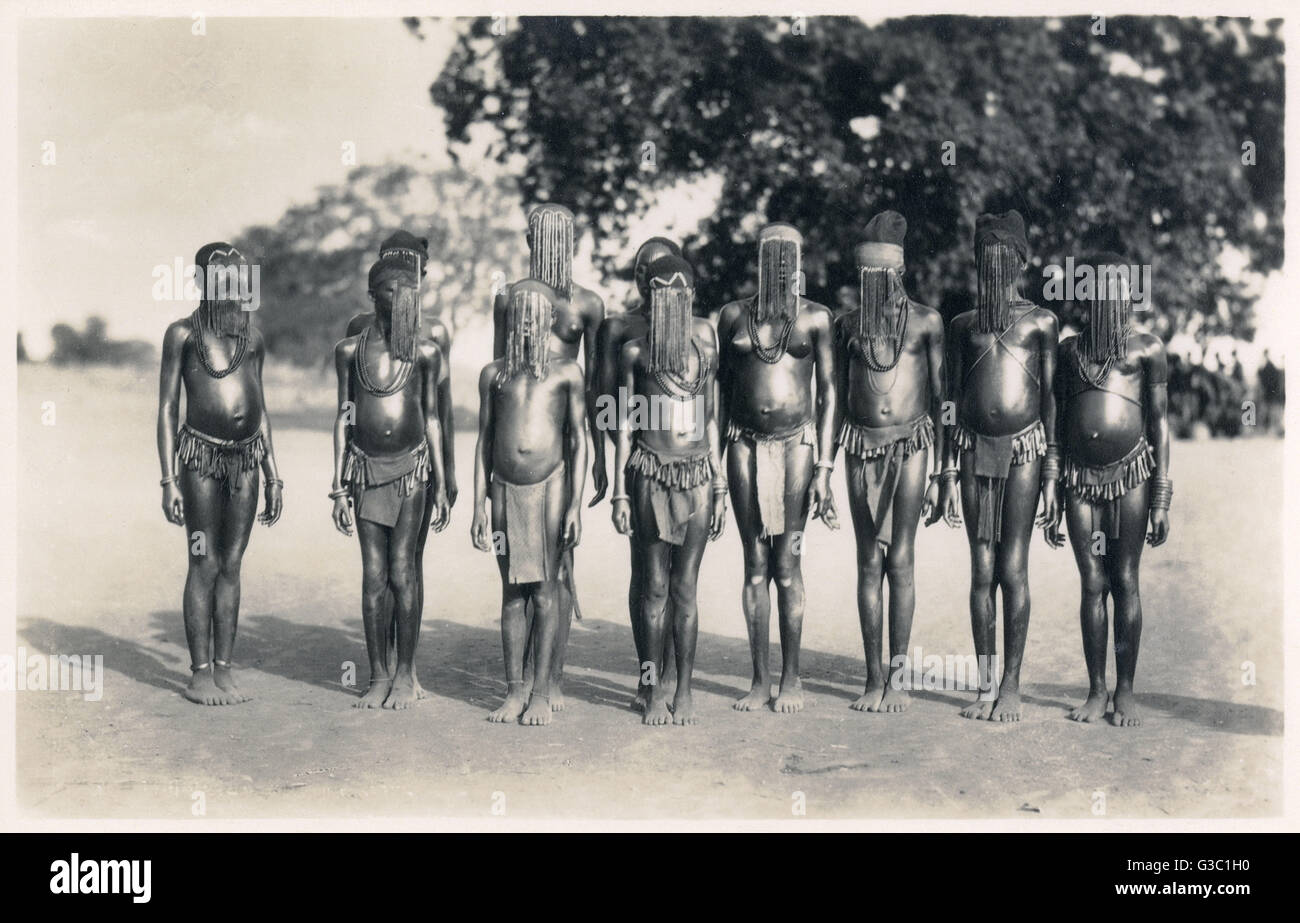

In some ethnic groups in Kenya or Sierra Leone, the procedure is part of a "rite of passage." It marks the transition from childhood to womanhood. There are often celebrations, gifts, and a newfound status within the tribe. If you opt out, you’re an outcast. You’re a child forever in the eyes of your elders.

There's also this persistent myth about aesthetics and hygiene. You’ll hear practitioners argue that female genitalia are "bulky" or "ugly" and that removing parts of them makes a woman "clean." It’s a classic example of cultural body dysmorphia enforced on a massive scale. Dr. Nafissatou Diop, a long-time expert with the UNFPA, has often pointed out that these beliefs are so deeply internalized that women themselves become the primary gatekeepers of the practice.

📖 Related: Grab bars for elderly: Why your bathroom is probably less safe than you think

Does religion play a role?

This is a sticky point. Many people assume it’s a religious requirement, particularly in Islam. But here’s the thing: it’s not in the Quran. While some local religious leaders might advocate for it or claim it’s "sunnah" (recommended), many of the highest Islamic authorities have issued fatwas against it.

You find FGM among Christians, Muslims, and even some Jewish communities (like the Beta Israel in Ethiopia, though the practice has largely stopped since their migration to Israel). It’s a pre-Islamic practice that hitched a ride on various religions as they spread. Basically, it’s more about where you live than what you believe.

The different "types" and what they actually involve

Not all procedures are the same. The World Health Organization (WHO) breaks it down into four categories, and they range from "minor" (though nothing about this is minor) to extreme.

- Type 1 (Clitoridectomy): Partial or total removal of the clitoral glans.

- Type 2 (Excision): Removal of the clitoral glans and the labia minora.

- Type 3 (Infibulation): This is the most severe. The vaginal opening is narrowed by creating a covering seal. This is done by cutting and repositioning the labia. A small hole is left for urine and menstrual blood.

- Type 4: This is a catch-all for everything else—pricking, piercing, incising, or scraping the genital area.

Think about that for a second. Type 3 requires the woman to be "de-infibulated" (cut open) just to have intercourse or give birth, and then often "re-infibulated" afterward. The sheer physical toll is staggering.

The medical reality: What happens after the "why"

The reasons behind why do they do female circumcision often crumble when faced with the medical consequences. There are zero health benefits. None.

In the short term, the risks are immediate: severe pain, shock, hemorrhage, and infections like tetanus or sepsis. Because these procedures are often done with unsterile tools—think razor blades, glass, or even sharpened stones—the risk of HIV transmission is a real concern.

Long-term? It’s a lifetime of complications. Chronic pain. Recurrent urinary tract infections. Keloid scarring that makes movement painful. Then there’s the obstetric side. Women who have undergone FGM are significantly more likely to experience prolonged labor, tears, and postpartum hemorrhage. Their babies are at higher risk of neonatal death.

Then there’s the psychological weight. PTSD, anxiety, and depression are incredibly common. It’s a fundamental betrayal of trust, usually occurring at an age where the girl can’t fully comprehend why her caretakers are causing her such intense pain.

The "Medicalization" Trap

Lately, there’s been a weird and worrying trend. More people are having the procedure done by doctors or nurses in clinics rather than traditional practitioners in a village. This is called "medicalization."

The logic seems sound on the surface: "If it’s going to happen anyway, let’s do it in a sterile environment with anesthesia."

But this is a trap. It gives the practice a veneer of legitimacy. It suggests there’s a "safe" way to perform a human rights violation. Organizations like UNICEF are fighting hard against this because it makes the practice harder to eradicate. When a doctor does it, the parents feel justified. They think they’re being modern and "safe." But you’re still removing healthy tissue and causing lifelong trauma.

Is it actually going away?

Yes. But slowly.

The data shows a decline in most countries where FGM is prevalent. In Egypt, for instance, the numbers among younger girls are dropping compared to their mothers’ generation. In 2008, the UN passed a resolution to end FGM, and many countries have since criminalized it.

👉 See also: Why Twin Valley Behavioral Healthcare Hospital Photos Don't Tell the Whole Story

But laws don't always change hearts.

In some places, the practice has just gone underground. Families cross borders to countries with more lenient laws—a phenomenon known as "vacation cutting." Real change happens when the whole community agrees to stop at once. If only one family stops, their daughter is still "unmarriageable." If the whole village decides to end it, the social pressure evaporates.

Programs like Tostan in Senegal have seen massive success with this "community-led" approach. They don't just lecture people on health; they facilitate long-term discussions about human rights and democracy. When the community chooses to abandon the practice together, it actually sticks.

Taking action and understanding the shift

Understanding why do they do female circumcision is the first step toward supporting the people working to end it. It’s not about judging a culture from a distance; it’s about supporting the women within those cultures who are already leading the charge for change.

If you want to contribute to the end of this practice or learn more, here are the most effective ways to engage:

Support local grassroots organizations

Don’t just give to massive, faceless NGOs. Look for groups like Safe Hands for Girls (founded by survivor Jaha Dukureh) or The Orchid Project. These organizations work directly with survivors and community leaders who understand the nuances of their own culture.

Education over condemnation

If you are talking to someone from a practicing community, realize that "it’s barbaric" is a conversation-ender. Instead, focus on the health outcomes and the fact that many religious scholars have debunked the necessity of the practice. Change comes through dialogue, not shaming.

🔗 Read more: Garden of Life Women's Once Daily Probiotic: What the Label Doesn't Tell You

Advocate for legislative protection

In many Western countries, "vacation cutting" is still a loophole. Support legislation that makes it a crime to take a child abroad for the purpose of FGM. Ensure that healthcare providers in all countries are trained to recognize the signs of FGM and provide culturally sensitive care to survivors.

Focus on the youth

The biggest shift is happening in schools. When girls are educated about their bodies and their rights, they become the generation that says "no" for their own daughters. Supporting girls' education in high-prevalence areas is arguably the most effective long-term strategy to end FGM/C forever.

The practice exists because of a deeply flawed belief that a woman's value is tied to her physical "purity" and her obedience to tradition. As that definition of value changes, the practice dies. It’s a slow process, but for the millions of girls at risk, it’s a race against time.