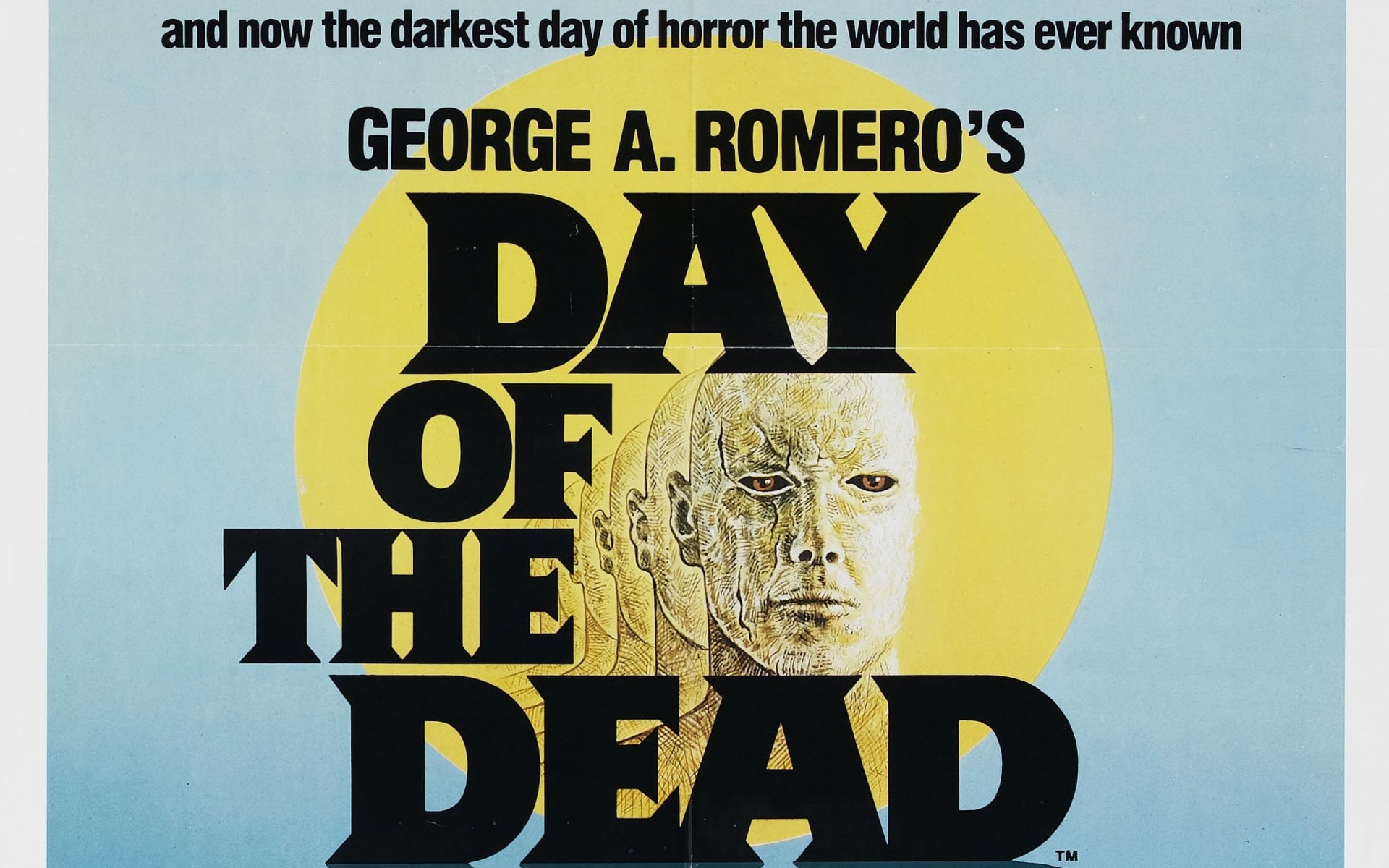

George A. Romero didn't want to make a compromise. He wanted to make a revolution. When people talk about the "holy trinity" of zombie cinema, they usually start with the stark monochrome terror of Night of the Living Dead or the mall-crawling consumerist satire of Dawn of the Dead. But the day of the dead movie 1985 is the one that actually hurts to watch. It’s loud. It’s claustrophobic. It’s incredibly mean-spirited in a way that feels uncomfortably honest about how humans behave when the lights go out for good.

The film didn't have it easy. Romero originally envisioned an epic—a "Gone with the Wind" of zombie movies. He wanted an underground fortress, an army of trained ghouls, and a massive scale that would have redefined the 80s horror landscape. Then the money men stepped in. They offered a choice: make a PG-13 movie with a bigger budget, or keep the gore and take a massive pay cut. Romero, being the stubborn genius he was, chose the gore. He chose the art.

The Underground Pressure Cooker

The setting is a literal hole in the ground. An old limestone mine in Pennsylvania serves as the backdrop for the final stand of humanity, or at least a very small, very angry cross-section of it. You have the scientists, led by Sarah (Lori Cardille), desperately trying to find a cure or a reason to keep going. Then you have the military, led by Captain Rhodes (Joseph Pilato), who is essentially a walking heart attack of toxic masculinity and unhinged rage.

It's a powder keg.

The day of the dead movie 1985 thrives on this friction. While Dawn was about the excitement of having everything for free, Day is about the realization that everything is gone. There is no hope. The zombies outnumber the living 400,000 to one. Think about that ratio for a second. It's not a war; it's a funeral that hasn't finished yet.

Rhodes is perhaps the most effective human villain in horror history because he’s so believable. He isn't a cartoon. He’s a man who has lost his chain of command and is desperately trying to scream his way back into a position of power. His "Choke on 'em!" line wasn't just a script requirement; it was a defiant middle finger to the inevitability of death.

Why Bub Changed Everything

Then there’s Bub. If you haven't seen the film, Bub is the zombie played by Howard Sherman who starts to... remember. He listens to music. He "shaves." He recognizes the authority of Dr. Logan, whom the soldiers affectionately call "Frankenstein."

🔗 Read more: All I Watch for Christmas: What You’re Missing About the TBS Holiday Tradition

Bub is the emotional core of the day of the dead movie 1985. By giving a zombie a personality, Romero did something incredibly dangerous for a horror director: he made us pity the monster. Logan’s theory was that the zombies are us, just simplified. They have memories. They have instincts. If you treat them with a shred of humanity, they might just mirror it back.

It's a radical idea. It moves the zombie from a mindless obstacle to a tragic figure. When Bub salutes or tries to read a book, it’s not funny. It’s heartbreaking. It suggests that the tragedy isn't just that we're dying, but that something of our souls lingers in the rot.

Tom Savini’s Magnum Opus

We have to talk about the blood. Honestly, the practical effects in this movie are bordering on the miraculous. Tom Savini, the "Sultan of Splat," reached his zenith here. Because Romero opted to go unrated, Savini was allowed to push the boundaries of what was physically possible with latex, pig intestines, and red syrup.

The "gut-munching" scenes in the day of the dead movie 1985 look better than most CGI-heavy blockbusters made forty years later. Why? Because there's a weight to it. When a body is torn apart in this film, it looks messy and difficult. It doesn't look like pixels; it looks like biology failing.

- The shovel decapitation? Iconic.

- The elevator floor stomach-rip? Genuinely nauseating even today.

- The practical textures of the zombies themselves—gray, leathery, and peeling.

Savini and his team, which included a young Greg Nicotero (who would later lead the charge on The Walking Dead), created a visual language of decay that hasn't been topped. They used real animal innards from a local butcher shop, which reportedly made the set smell so bad that some actors actually threw up during takes. That's commitment to the craft.

A Script That Screams

Romero’s dialogue in this film is unlike anything else in the series. It’s Shakespearean in its melodrama. Every character is at a breaking point. John and Bill, the helicopter pilots who just want to live in a trailer on a beach, provide the only breath of fresh air. John’s monologue about the "great record book" is the philosophical heart of the film. He argues that maybe we shouldn't be trying to fix things. Maybe we should just let the world go back to the earth.

💡 You might also like: Al Pacino Angels in America: Why His Roy Cohn Still Terrifies Us

He’s the voice of the audience. He sees the scientists and soldiers bickering and realizes they’re just rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.

The Legacy of a Box Office "Failure"

When it came out in July 1985, the movie didn't set the world on fire. It was too dark. It was too talky. Compared to the neon-soaked, synth-pop horror of the mid-80s, the day of the dead movie 1985 felt like a grim relic. People wanted Return of the Living Dead—they wanted "Send more paramedics" and punk rock. They didn't want a meditation on the failure of human communication set in a damp cave.

But time has been kind.

Actually, time has been more than kind. It has been a vindication. Modern critics often rank Day as the most intellectual of the bunch. It’s a movie about the Reagan era, about the Cold War, and about the fear that our institutions—the military, the scientific community—won't save us when the "big one" hits.

The film's influence is everywhere. You can see Bub's DNA in every "sympathetic" zombie story from Shaun of the Dead to Warm Bodies. You can see the claustrophobic military tension in every post-apocalyptic show on HBO.

What Most People Get Wrong

A common misconception is that the film is "anti-science" or "anti-military." It's actually pro-humanity, but deeply pessimistic about human ego. The scientists aren't the heroes just because they have lab coats. Logan is clearly insane. Sarah is the only one with her head on straight, and she spends the entire movie being ignored or threatened by men who think they know better.

📖 Related: Adam Scott in Step Brothers: Why Derek is Still the Funniest Part of the Movie

It’s a feminist text without shouting about it. Sarah is the survivor not because she’s the strongest, but because she’s the most adaptable. She is the only one willing to look at the reality of the situation without trying to bend it to her will.

Actionable Insights for Horror Fans

If you're revisiting the day of the dead movie 1985 or seeing it for the first time, there are a few things you should do to truly appreciate what Romero accomplished.

First, seek out the Blu-ray or 4K restorations. The film was shot in a real mine, and the lighting is intentionally oppressive. Older VHS or DVD transfers lose the incredible detail in the shadows and the nuances of the prosthetic makeup. You want to see the sweat on Rhodes' face.

Second, listen to the score by John Harrison. It’s a bizarre mix of Caribbean-influenced synth and mournful melodies. It shouldn't work. A zombie movie set in a dark pit shouldn't have steel drums. But it does, and it creates a "tropical vacation in hell" vibe that is entirely unique to this entry.

Third, watch it as a double feature with Dawn of the Dead. The transition from the colorful, consumerist excess of the mall to the gray, lifeless void of the mine is one of the most effective tonal shifts in cinema history. It tells the story of the end of the world better than any narration ever could.

The day of the dead movie 1985 remains a masterclass in tension and practical effects. It’s a reminder that horror works best when it has something to say about the people running away from the monsters, not just the monsters themselves. Romero knew that the zombies weren't the end of the world. We were.

Next Steps for the Ultimate Experience:

- Watch the "The Many Days of Day of the Dead" documentary. It covers the original "unfilmed" script which featured an army of zombies being trained to use weapons—a concept Romero eventually revisited in Land of the Dead.

- Compare the 1985 original to the 2008 and 2018 remakes. You will quickly see why the original's reliance on practical effects and character-driven tension makes the CGI-heavy remakes feel hollow and forgettable.

- Analyze the character of Private Salazar. Often overlooked, his descent into madness is a haunting portrayal of how the "average joe" breaks under the pressure of an unending nightmare.