Davey Johnson didn't care if you liked him. Honestly, he probably preferred it if you didn't, as long as you were winning.

He was a math major who somehow found himself leading the rowdiest, most cocaine-fueled, and most talented team in the history of New York City. We are talking about the 1986 Mets. But to label him just as the guy who happened to be steering the ship when Mookie Wilson’s grounder rolled through Bill Buckner’s legs is a massive mistake.

Davey Johnson was the first true "quant" in a dugout. Long before Billy Beane and Moneyball became household names, Davey was lugging around a clunky computer and telling Hall of Fame managers their lineups were garbage. He was a disruptor. He was arrogant. And he was almost always right.

The Computer in the Clubhouse

In 1984, when Johnson took over a Mets team that had won a measly 68 games the year before, he brought a secret weapon. It wasn't a new hitting coach or a revolutionary training program. It was a computer running dBase II.

The old-school baseball world hated it. They thought it was soft.

Johnson used the data to track every single matchup. He saw that on-base percentage (OBP) was more valuable than batting average. He saw that Wally Backman, despite not being the "star" Mookie Wilson was, was the superior leadoff hitter because he walked. He forced the Mets to play the odds. The result? They won 90 games his first year. Then 98. Then 108.

He didn't just manage the nine guys on the field. He managed the entire roster. He was a master of the platoon, frequently pulling stars if the numbers said a bench player had a better chance against a specific lefty.

💡 You might also like: Last place fantasy football: Why the loser's bracket is actually the heart of the league

"They don't hire you just to manage the nine guys on the field," Johnson once said. "They hire you to manage them all. And if you don't know how to do that, you've got no chance."

The 1986 Mets: A Dynasty of One

There is a specific kind of tragedy in Davey Johnson’s career. The 1986 Mets should have been a dynasty. With Dwight Gooden, Darryl Strawberry, and Keith Hernandez, they had the talent to win four titles in a row.

They only won one.

The wheels started to come off because Johnson’s "loose rein" style had a dark side. He treated his players like men, which in the 80s meant he didn't care what they did after the game. If you showed up and produced, he didn't give a damn if you stayed out until 4:00 AM.

✨ Don't miss: Kansas City Chiefs Sunday: Why the Mahomes Magic Always Feels Different in the Fourth Quarter

But as the 1988 NLCS loss to the Dodgers proved, you can’t always out-math a lack of discipline. The Mets dominated the Dodgers in the regular season, winning 10 of 11 games. Then, Mike Scioscia hit a soul-crushing home run off Doc Gooden in Game 4, and the momentum shifted forever. Johnson’s critics, including Mets GM Frank Cashen, started to whisper that he had lost control of the clubhouse.

By 1990, he was fired. The winningest manager in Mets history was out of a job because he was too stubborn to change his ways.

The Perpetual Winner and the Owners Who Hated Him

If you look at his career as a whole, a weird pattern emerges. Everywhere Davey Johnson went, the team immediately got better. And almost everywhere he went, he got into a fight with the owner and ended up leaving.

- Cincinnati Reds: He took over in 1993 and had them in first place by 1994 when the strike hit. In 1995, they won the division. But owner Marge Schott hated him so much she announced mid-season that he wouldn't be back, regardless of whether he won the World Series.

- Baltimore Orioles: He led them to the best record in the American League in 1997. He won the Manager of the Year award. He resigned the same day he won the award because of a dispute with owner Peter Angelos over a $10,500 fine involving Roberto Alomar.

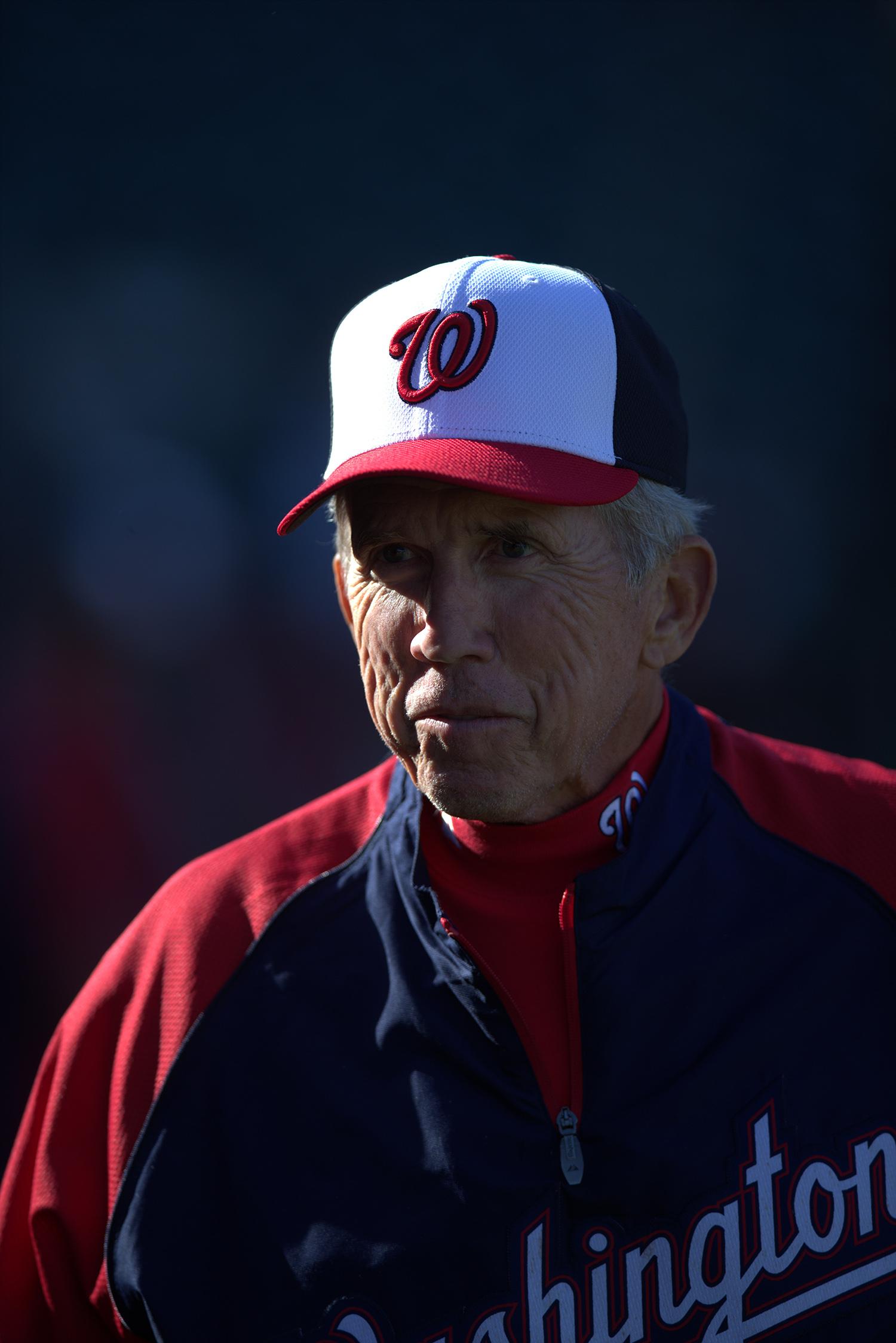

- Washington Nationals: In 2012, at nearly 70 years old, he led the Nats to 98 wins and their first-ever postseason berth.

He finished his career with a .562 winning percentage. That’s 10th all-time for managers with 1,000 wins. Most of the guys ahead of him are in the Hall of Fame.

Why He’s Not in Cooperstown (Yet)

Davey Johnson passed away in September 2025 at the age of 82. His death reignited the debate about his legacy. Why isn't he in the Hall of Fame?

The argument against him is usually about longevity. He only managed 17 seasons. He moved around a lot. He didn't have the "lifetime achievement" vibe of a Connie Mack or a Bobby Cox.

But if the Hall of Fame is about impact and efficiency, he belongs. He was the bridge between the old-school "gut feeling" era and the modern "spreadsheet" era. He was the guy who got hit with a single off Sandy Koufax in Koufax's final game, and then decades later, he was the guy calling the shots for Bryce Harper.

He was a link between generations.

What You Can Learn from Davey's Career

If you're looking for actionable insights from the life of a baseball genius, here’s the reality of the Davey Johnson approach:

- Numbers aren't the enemy, but they aren't the answer either. Johnson loved his computer, but he always said you had to allow for "gut feeling." Use data to inform your decisions, not to make them for you.

- Conflict is often the price of competence. If you are a disruptor, you are going to piss people off. Johnson’s career proves that you can be the best in the world at what you do and still get fired if you can't manage up.

- Optimize your "lineup" daily. Whether it’s your business team or your personal schedule, small adjustments in order and placement lead to massive gains over time. Johnson found 50 extra runs just by moving himself up in the batting order. Where are your 50 runs hiding?

Davey Johnson lived a life of baseball. He hit 43 home runs as a second baseman in 1973—a record that stood for nearly 50 years. He won World Series as a player and a manager. But mostly, he was a guy who refused to be a "statistic in somebody else's computer." He wanted to be the one writing the program.

To truly understand the modern game, you have to look back at the guy who was doing it in 1984 with a floppy disk and a chip on his shoulder. Study the 1986 Mets season to see how he balanced ego and analytics. Review his 1997 season in Baltimore to understand why standing on principle—even over a relatively small fine—is what defined his character.

His story isn't just about baseball; it's about the relentless pursuit of an edge.