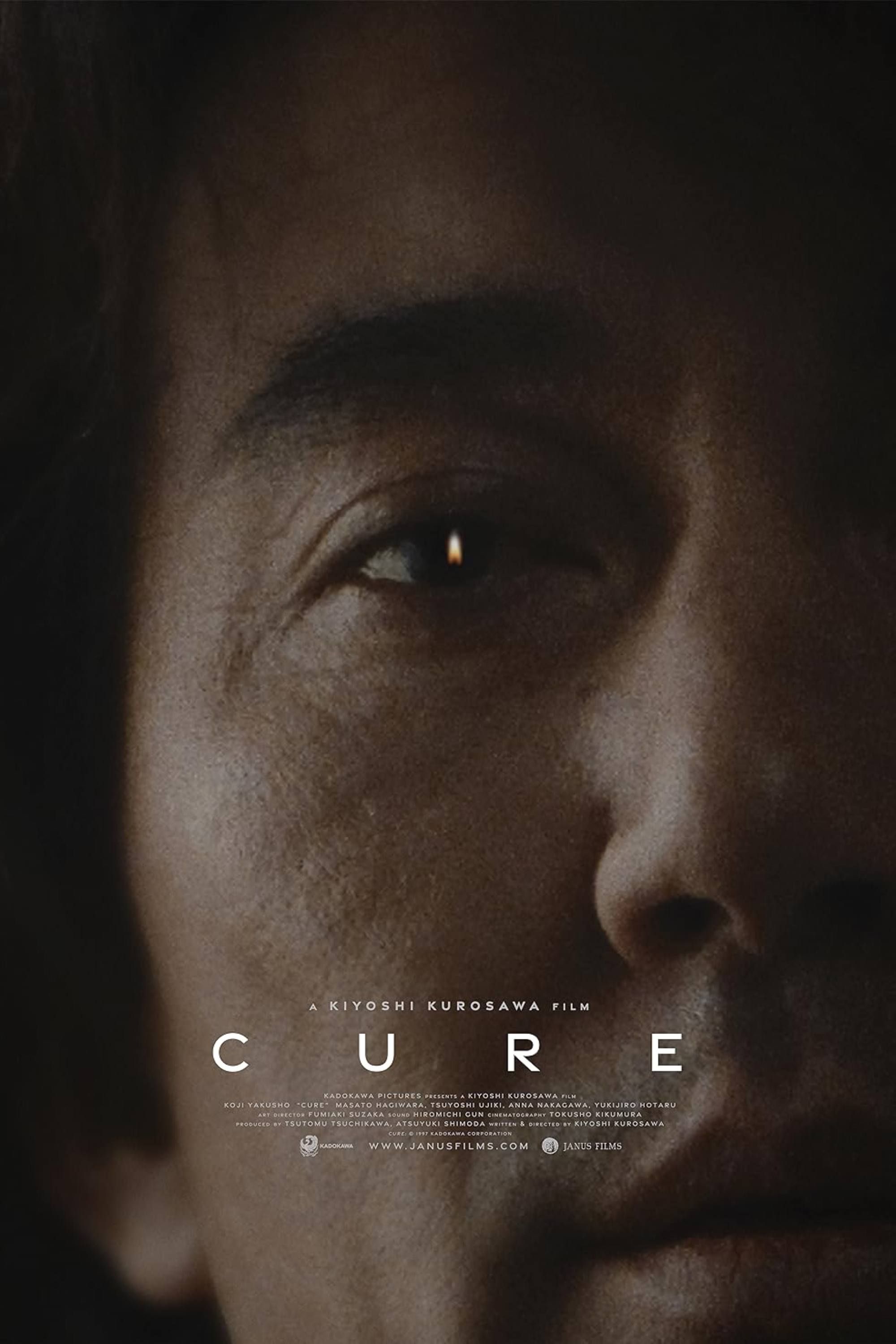

You’re sitting in a dark room. The silence isn't peaceful; it’s heavy. On the screen, a man stands in a drab apartment, his movements jerky and wrong. He asks a simple question: "Who are you?" It sounds innocent. It isn't. By the time the credits roll on Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Cure 1997 movie, you aren't just scared of the dark anymore. You’re scared of the person sitting next to you. You might even be scared of yourself.

Kiyoshi Kurosawa—no relation to Akira, though he’s just as much of a master—released this film right at the tail end of the 20th century. It arrived during a massive boom in Japanese horror. But while Ringu was busy making us afraid of VHS tapes and pale girls in wells, Cure 1997 was doing something much more surgical. It was dismantling the idea of the human soul. Honestly, it’s one of the few films that actually feels dangerous to watch.

What Actually Happens in Cure?

The plot seems like a standard police procedural at first. Detective Kenichi Takabe, played by the legendary Koji Yakusho, is investigating a string of gruesome murders. The MO is identical: a large "X" is carved into the victim's neck. Here is the catch—the killers are all different people. They are caught at the scene. They have no motive. They usually don't even remember doing it. They just... snapped.

Takabe is a man on the edge. His wife is struggling with severe mental illness, and his home life is a cycle of repetitive, empty tasks. Then he meets Mamiya. Mamiya is a former psychology student who appears to have total amnesia. He wanders the beach. He asks people for a light. And then he starts asking them questions.

Who are you? Tell me about yourself.

✨ Don't miss: Why October London Make Me Wanna Is the Soul Revival We Actually Needed

It’s not long before you realize Mamiya isn't the one who is lost. He’s the one who found something. He uses a form of mesmerism—basically a hardcore, weaponized version of hypnosis—to strip away a person's social facade. He finds the resentment buried deep in the "normal" people he meets and brings it to the surface. He doesn't tell them to kill. He just removes the part of their brain that says "don't."

The Visual Language of Dread

Kurosawa doesn't use jump scares. Not one. Instead, he uses long, wide shots where the camera stays still for an uncomfortably long time. You see a character in the background of a shot, and they just stay there. Watching.

The sound design is arguably the most important part of the Cure 1997 movie. It’s full of industrial hums, the sound of dripping water, and the crackle of fire. It creates a sensory environment that feels like a fever dream. When Mamiya flickers a lighter or pours water onto a table, the sound is magnified. It’s hypnotic for the audience, too. You start to feel the same trance-like state that the victims feel. It’s effective because it’s subtle.

Most horror movies try to make you scream. Cure tries to make you stop breathing.

🔗 Read more: How to Watch The Wolf and the Lion Without Getting Lost in the Wild

Why Mamiya is the Ultimate Villain

Mamiya isn't a slasher. He isn't a ghost. He’s barely even a person. Masato Hagiwara plays him with this terrifying, limp-noodle energy. He’s vacant. He repeats questions because he doesn't care about the answers; he only cares about the vibration of the words.

Think about how we live today. We spend so much energy pretending to be okay. We follow rules. We go to jobs we hate. We smile at neighbors we don't like. Mamiya looks at that and sees a cage. He thinks he’s "curing" people by letting their true, violent impulses out. It’s a dark take on therapy. Instead of healing the mind to fit into society, he breaks the mind so society no longer matters.

The Philosophical Core: Mesmerism and the "X"

The movie dives deep into the history of Franz Mesmer and the origins of animal magnetism. It suggests that there is a literal frequency or "fluid" that can be manipulated to control others. This isn't just movie magic; it’s based on the real-world anxieties of the late 90s. In 1995, Japan dealt with the Tokyo subway sarin attack by the Aum Shinrikyo cult. People were terrified of the idea of "mind control" and how easily a charismatic leader could turn normal citizens into killers.

Cure captured that national trauma perfectly. The "X" isn't just a mark; it’s a cancellation. It represents the crossing out of the ego. When Takabe finally confronts Mamiya, it’s not a battle of strength. It’s a battle of wills. Can a man who is defined by his duty and his love for his wife survive a man who has no identity at all?

💡 You might also like: Is Lincoln Lawyer Coming Back? Mickey Haller's Next Move Explained

Why the Ending Still Sparks Debates

The final scene of the Cure 1997 movie is one of the most chilling "quiet" endings in cinema history. There are no explosions. No final girl screaming. Just a simple lunch in a restaurant.

If you watch the background of the final shot, you’ll see something happen that suggests the "infection" hasn't stopped. It has evolved. Kurosawa suggests that once you’ve seen the truth—once you’ve looked into the void that Mamiya represents—you can’t just go back to being a normal detective. The darkness is contagious.

How to Experience Cure Today

If you're going to watch this, do it right.

- Turn off the lights. This isn't a "second screen" movie. If you’re checking your phone, you’ll miss the subtle shifts in the background that build the tension.

- Pay attention to the laundry. It sounds weird, but the recurring image of a washing machine or clothes spinning is a major motif for the cyclical nature of the characters' lives.

- Watch for the water. Fire and water are Mamiya’s tools. Every time you see a glass of water or a puddle, something is about to shift.

Where to Find It

The film is currently part of the Criterion Collection, which means the restoration is gorgeous. You can usually find it streaming on the Criterion Channel or HBO Max (depending on your region). If you’re a physical media nerd, the 4K restoration is the way to go because the shadows in this movie are incredibly deep and lose detail on low-bitrate streams.

Final Actionable Steps for Film Fans

If you’ve already seen Cure 1997 and want to dive deeper into this specific brand of "J-Horror" that focuses on urban alienation rather than ghosts, here is what you should do next:

- Watch "Pulse" (Kairo) by the same director. It’s the spiritual successor to Cure and deals with the internet being haunted. It’s arguably even more depressing.

- Read up on the Aum Shinrikyo cult. Understanding the atmosphere of Japan in the mid-90s adds a massive layer of political context to Mamiya’s character.

- Analyze the "long take." Pick one scene in Cure—like the one in the doctor's office—and watch it without looking at the subtitles. Just watch how the camera moves (or doesn't move). It’s a masterclass in blocking.

- Look into the works of Shin'ya Tsukamoto. If you liked the grimy, industrial feel of Cure, Tetsuo: The Iron Man is the logical, albeit much more chaotic, next step.

The Cure 1997 movie isn't just a horror film; it's a psychological mirror. It asks you what you’re hiding behind your "normal" face. And honestly? You might not like the answer.