The ground feels solid. You walk on it, build skyscrapers on it, and bury your secrets in it. But beneath that deceptive stillness, the entire planet is basically a giant, slow-motion lava lamp. The Earth's surface isn't a single shell; it's a cracked mosaic of massive slabs. We call them tectonic plates. They’re heavy. They’re stubborn. And yet, they’re constantly drifting, crashing, and grinding.

So, what causes crustal plates to move?

If you went to school in the 90s, you were probably told it was all about convection currents—giant loops of hot rock rising and falling like boiling soup. It’s a clean explanation. It’s easy to draw on a chalkboard. It’s also mostly incomplete. Geologists now know that while convection is the engine, it isn't necessarily the driver. The real story involves a violent tug-of-war between gravity, heat, and the sheer density of the ocean floor.

The Convection Engine: Why the Mantle Isn't Actually Liquid

To understand the movement, you have to ditch the idea that the mantle is a sloshing ocean of orange juice. It isn't. The mantle is solid rock. However, under the intense heat and pressure of the Earth’s interior, that rock behaves like "Rheid"—a solid that flows over incredibly long timescales. Think of it like Silly Putty. If you hit it with a hammer, it shatters. If you leave it on a table for a week, it puddles.

Heat from the core, much of it left over from the planet’s violent birth and the radioactive decay of elements like potassium-40 and uranium-238, warms the base of the mantle. This warm rock expands slightly. It becomes less dense. It rises. As it reaches the cooler upper layers near the crust, it spreads out, cools, and eventually sinks back down.

This creates a circular motion. For decades, the consensus was that the crust just "surfed" on top of these cycles. But here is the catch: the friction between the flowing mantle and the bottom of the plate isn't always strong enough to move a continent. Something else is pulling.

Slab Pull: The Heavy Lifter of Tectonics

Most geologists today, including researchers at institutions like the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, argue that Slab Pull is the dominant force. This is where things get interesting.

👉 See also: Ethics in the News: What Most People Get Wrong

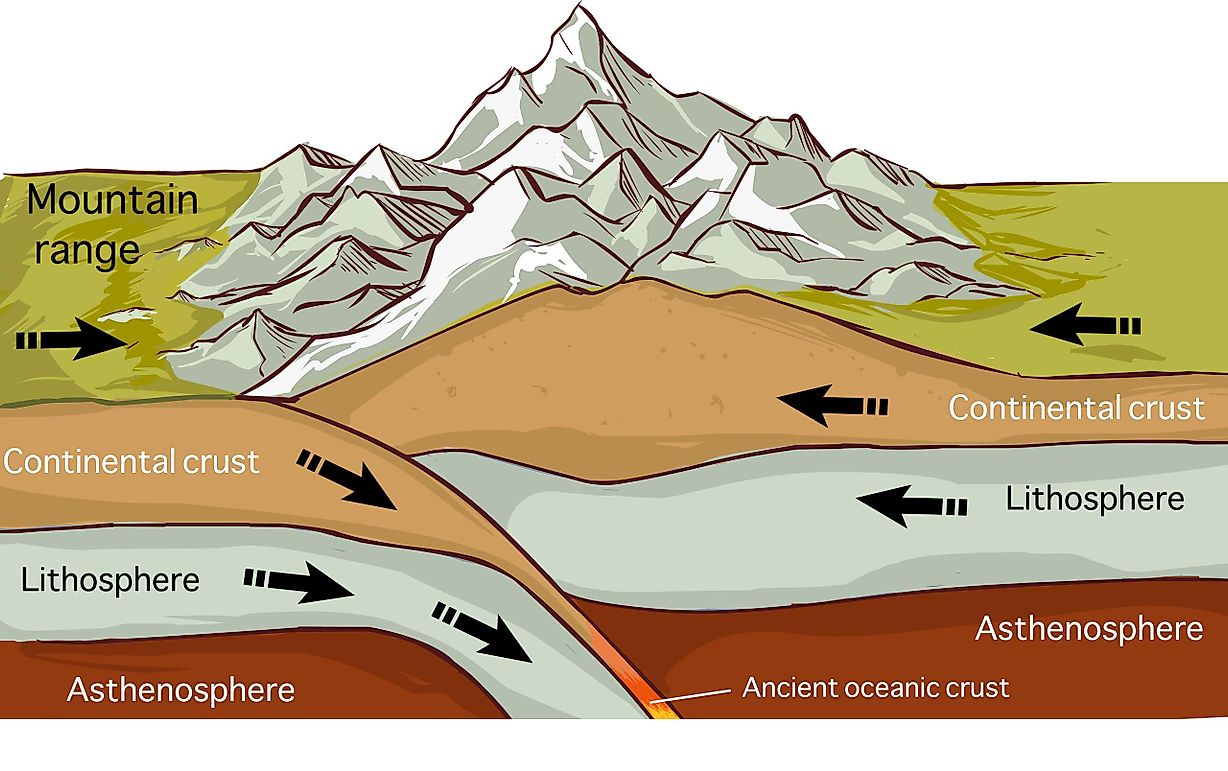

When oceanic crust moves away from a mid-ocean ridge, it cools down. As it cools, it gets thicker and much denser. Eventually, it becomes denser than the mantle beneath it. When that heavy edge of the plate starts to sink into the mantle at a subduction zone—like the one along the western coast of South America—it doesn't just fall. It pulls the rest of the plate behind it.

Imagine a heavy rug sliding off a table. Once enough of the rug hangs over the edge, the weight of the dangling part pulls the rest of the rug down with it. That’s slab pull. It is a relentless, gravity-driven process that accounts for the vast majority of plate speed. Plates attached to large subducting slabs, like the Pacific Plate, move significantly faster than plates that don't have them, like the African Plate. Gravity is doing the heavy lifting.

Ridge Push: Pushing from the Middle

While the "front" of the plate is being pulled into the depths, the "back" of the plate is getting a nudge. This is Ridge Push.

At mid-ocean ridges, like the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, new magma rises to the surface, creating fresh crust. This area is hot and elevated, forming a long underwater mountain range. Because this ridge is higher than the surrounding ocean floor, the newer, warmer rock sits at a higher gravitational potential.

Gravity again. The weight of the elevated ridge pushes the rest of the plate away from the center. It’s not as powerful as slab pull, but it contributes to the momentum. Basically, the plate is being pushed off a hill at one end and dragged into a hole at the other.

The Role of Water (The Secret Lubricant)

You wouldn't think water matters ten miles underground, but it's the "grease" that makes the whole system work. When an oceanic plate subducts, it carries minerals that have water trapped in their crystal structures.

✨ Don't miss: When is the Next Hurricane Coming 2024: What Most People Get Wrong

As the slab sinks and heats up, it "sweats." This water lowers the melting point of the surrounding mantle and softens the rocks. Without this hydration, the plates might be too stiff to move effectively. Earth is the only planet we know of with active plate tectonics, and many scientists believe our liquid oceans are the reason why. Venus is a similar size and has plenty of heat, but it’s bone-dry and its crust appears stuck in a single, stagnant lid. No water, no slide.

Why Some Plates Are Just Faster

Not all plates are created equal. The North American Plate is a bit of a slow poke, moving at about 2.3 centimeters per year—roughly the speed your fingernails grow. Meanwhile, the Nazca Plate and the Pacific Plate are racing at over 10 centimeters per year.

Why the discrepancy?

It comes down to the "drag" of continents. Continental crust is thick, buoyant, and has deep "roots" that extend into the mantle. These roots create basal drag. A plate carrying a massive continent like Eurasia has to fight a lot more friction than a thin oceanic plate. It’s like trying to pull a boat through water versus dragging a plow through mud. The oceanic plates are the sprinters; the continents are the anchors.

What Most People Get Wrong About "The Big One"

We often talk about plate movement in the context of disasters. We think of the San Andreas Fault or the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake in Japan. We tend to think of these movements as sudden.

The reality? The movement is constant and smooth deep down. The "earthquake" part only happens at the very surface where the rocks are cold and brittle. In the top 10–15 miles of the crust, the plates get stuck. They lock together. The forces we’ve talked about—slab pull and ridge push—keep acting on them, building up immense elastic energy.

🔗 Read more: What Really Happened With Trump Revoking Mayorkas Secret Service Protection

When the rock finally snaps, it’s not that the plate "started" moving. It’s that the surface finally caught up to what the rest of the plate has been doing for decades.

How We Actually Know This is Happening

We aren't just guessing. Before the 1960s, the idea of "Continental Drift" was mocked. Alfred Wegener, the guy who proposed it, was largely ignored because he couldn't explain how the continents moved. He thought they plowed through the ocean floor like icebreakers. He was wrong about the mechanism, but right about the movement.

Today, we use Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI) and Global Positioning System (GPS) stations bolted into solid bedrock. We can literally watch the Atlantic Ocean get wider by a few inches every time we check the data. We also use seismic tomography—basically a CAT scan for the Earth. By measuring how earthquake waves speed up or slow down, we can "see" the cold, dead slabs of old tectonic plates sinking thousands of miles toward the core.

The Big Picture: Why It Matters

Understanding what causes crustal plates to move isn't just an academic exercise. It’s the reason we have an atmosphere. Plate tectonics acts as a global thermostat. It recycles carbon. When subduction carries carbon-rich sediments into the mantle, volcanoes eventually spit that $CO_2$ back out. This cycle prevents the Earth from freezing over or turning into a runaway greenhouse like Venus.

It also creates our resources. Most of the world's copper, gold, and silver deposits are found near old or active plate boundaries, where the intense heat and chemical-rich fluids of subduction concentrated these metals into veins we can mine.

Practical Insights and Next Steps

If you're interested in the ground beneath you, there are ways to track this in real-time. The Earth isn't finished changing.

- Monitor Real-Time Movement: Visit the USGS Earthquake Map to see where the stress of plate movement is currently being released. Look for the "ring of fire"—it's where the most aggressive slab pull is happening.

- Explore Local Geology: Check if you live near a "passive margin" (like the U.S. East Coast) or an "active margin" (like the West Coast). This determines your risk for everything from tsunamis to long-term sea-level change.

- Visualize the Future: Use interactive tools like Ancient Earth by Ian Webster to see where your current city was 200 million years ago and where it's projected to be in the next 50 million. Hint: California is heading toward Alaska.

The movement of the Earth's crust is a brutal, elegant system driven by the simple reality that hot things rise, cold things sink, and gravity never takes a day off. It is the pulse of a living planet.