You’re sitting there, coffee getting cold, staring at a grid that seems specifically designed to make you feel like you forgot how to speak English. It’s a Tuesday. Or maybe a "Grey’s Anatomy" themed Thursday. Either way, you’re locked in. That’s the magic of the crossword puzzles New York Times editors have been curating since the 1940s. It isn’t just a game. It’s a ritual. Honestly, it’s a weirdly personal relationship between you and a person you’ve never met—the constructor—who is currently laughing at you from behind a clever pun.

Most people think crosswords are for "smart people." That's a total lie. Crosswords are for people who are good at learning how one specific guy, Will Shortz (and now Joel Fagliano), thinks about the world. It’s about pattern recognition, not just vocabulary. If you know that a three-letter word for "Japanese sash" is always OBI, you aren't necessarily a genius; you've just played the game enough to know the tropes.

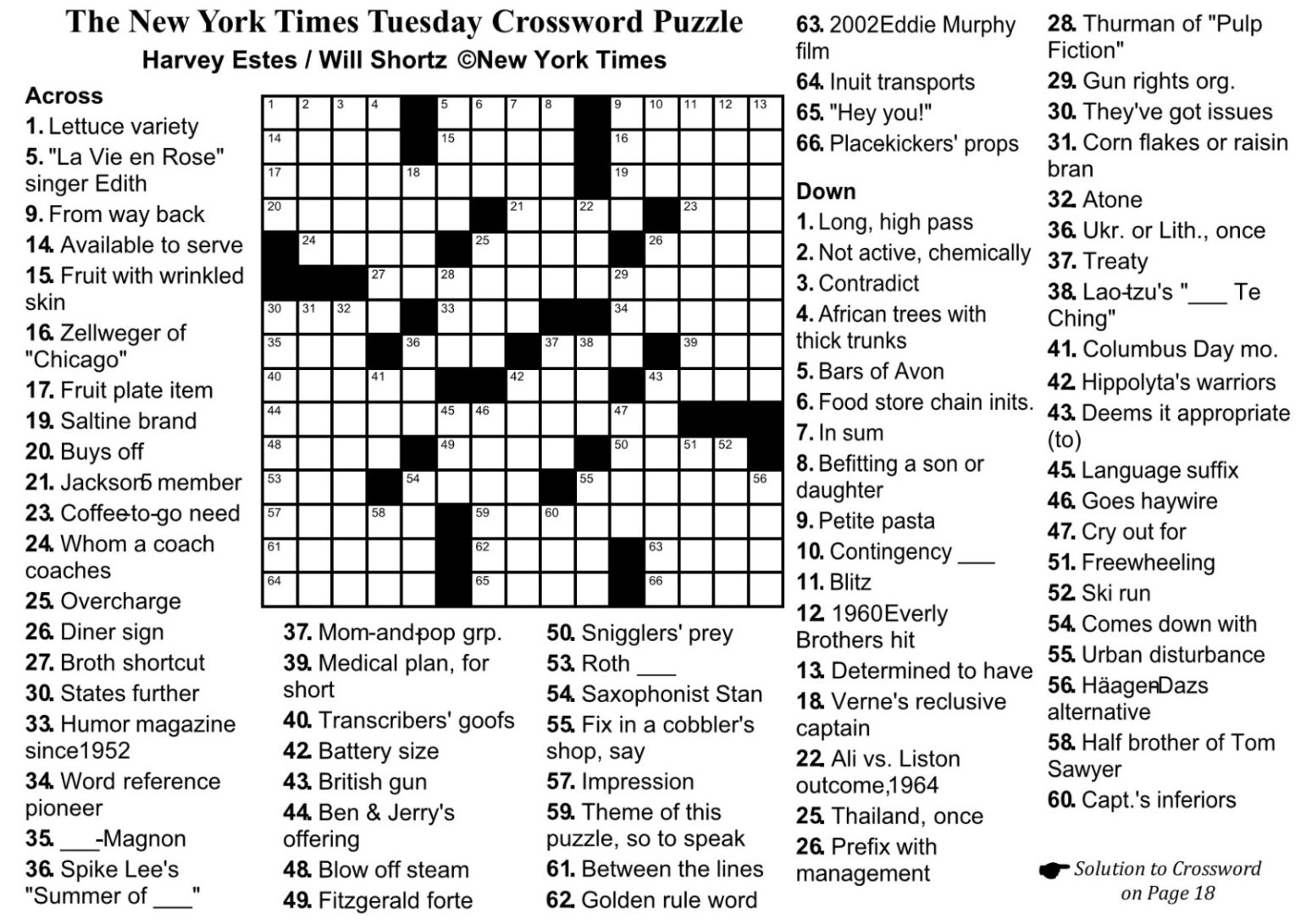

The Architecture of the New York Times Grid

The NYT crossword isn't a monolith. It evolves. If you jump into a Saturday puzzle without knowing the "rules of the week," you’re going to have a bad time.

Monday is the "confidence builder." It's straightforward. The clues are literal. If the clue says "Feline," the answer is CAT. By Wednesday, things get weird. The puns start creeping in. You might see a question mark at the end of a clue—that’s the international symbol for "I am lying to you." A clue like "Finish a flight?" for a Thursday puzzle isn't about airplanes. It’s about LANDING on a staircase.

Thursday is the day the NYT gets experimental. This is where you find the "rebuses." A rebus is a fancy way of saying "I’m going to shove an entire word or symbol into a single square." It breaks the rules of the grid. Some people hate it. Others live for the "Aha!" moment when they realize the word HEART has to be drawn as a little symbol to make the crossing words work.

Friday and Saturday are the "themeless" monsters. No gimmicks here. Just long, sprawling words and obscure trivia that requires you to know both 17th-century opera and 21st-century TikTok trends. Sunday is the big one. It isn't actually the hardest—that honor goes to Saturday—but it’s the largest. It’s a marathon of endurance.

✨ Don't miss: S.T.A.L.K.E.R. 2 Unhealthy Competition: Why the Zone's Biggest Threat Isn't a Mutant

The Will Shortz Era and the Shift to Modernity

Will Shortz took over as editor in 1993. Before him, the puzzles were a bit... dusty. They relied heavily on "crosswordese"—those words like ESNE (a slave) or ETUI (a needle case) that nobody has used since the 1800s but fit perfectly into tight grids. Shortz changed the vibe. He wanted cultural relevance. Suddenly, you had clues about THE SIMPSONS or NWA.

He famously said that a good puzzle should be "solvable by a person who is reasonably well-educated and keeps up with the world." That’s the secret sauce. The crossword puzzles New York Times publishes today feel alive. They reference memes, current politicians, and slang like YEET or SUS. It keeps the game from becoming a museum piece.

Of course, the transition hasn't been without drama. The "Old Guard" sometimes complains that the puzzles are getting "too woke" or "too young." Meanwhile, younger solvers get frustrated when they have to know the name of a character from a 1950s radio play. It’s a constant tug-of-war.

How to Actually Get Better at Solving

If you’re struggling, stop trying to be a hero. Start with Mondays. Seriously. Solve every Monday for a month. Then move to Tuesdays. You have to build the "crossword muscle."

- Trust the fill. If you have S_A_K, it’s probably SHARK or SNACK. Don’t overthink it.

- Look for the plurals. If a clue is plural, the answer almost always ends in S. Fill that S in immediately. It gives you a starting point for the crossing word.

- Abbreviations are telegraphed. If the clue uses an abbreviation (like "Govt. agency"), the answer will be an abbreviation (like FBI or IRS).

- Check the "fill-in-the-blanks." These are usually the easiest "gimmes" in the grid. "___ and cheese" is almost certainly MAC.

There’s also the digital aspect. The NYT Games app has changed everything. You get a little "happy music" chime when you finish a puzzle correctly. It’s addictive. The app also tracks your "streak"—the number of consecutive days you’ve finished the puzzle without using the "Check" or "Reveal" functions. People take their streaks very seriously. Losing a 400-day streak is a genuine tragedy in some households.

🔗 Read more: Sly Cooper: Thieves in Time is Still the Series' Most Controversial Gamble

The Controversy of "Crosswordese" and Inclusivity

In recent years, the crossword world has faced a reckoning. For a long time, the puzzles were constructed mostly by white men. This led to a very specific "point of view" in the clues. If you didn't know much about classical music or golf, you were at a disadvantage.

Groups like the Crossword Puzzle Collaboration Directory have stepped in to mentor underrepresented constructors. We’re seeing more clues about hip-hop, African American history, and queer culture. This isn't just about being "PC"—it makes the game more interesting. It broadens the vocabulary. A puzzle that includes LIZZO alongside LISZT is just a better, more accurate reflection of the world we live in.

It's also worth noting that the NYT isn't the only game in town anymore. The New Yorker has a fantastic, albeit difficult, crossword. The Atlantic has a "mini" that is lightning-fast. But the NYT remains the "Paper of Record." Getting a puzzle published in the Times is still the ultimate goal for any aspiring constructor. It pays the best, and it has the most eyes on it.

Behind the Scenes: The Life of a Constructor

Constructing a puzzle is a brutal, often thankless job. You start with a "seed" idea—usually a theme. Maybe it’s words that start with "Blue" or phrases that hide a secret message. You build the grid around that.

Modern constructors use software like Crossfire or KotWords to help manage the letter combinations, but the "soul" of the puzzle is still human. You have to write the clues. A good clue is a work of art. It needs to be tricky but fair.

💡 You might also like: Nancy Drew Games for Mac: Why Everyone Thinks They're Broken (and How to Fix It)

The pay for a 15x15 daily puzzle is currently $500. For a Sunday, it’s $1,500. That might sound like a lot, but when you consider the dozens of hours spent refining the grid and the fact that the rejection rate is incredibly high, it’s a labor of love. Most constructors have day jobs. They are teachers, programmers, and librarians who just happen to be obsessed with the letter Q.

Why We Keep Coming Back

Why do we do this to ourselves? Why spend twenty minutes of a perfectly good morning feeling stupid?

Because of the "click."

That moment when the nonsense letters in your brain suddenly align into a coherent word. It’s a shot of dopamine. In a world that feels chaotic and unfixable, the crossword is a problem that actually has a solution. There is a right answer. There is an end. You can fill every box, close the app, and feel like you’ve conquered something.

The crossword puzzles New York Times produces are a bridge between generations. You can talk to your grandfather about the Saturday puzzle, even if you solved it on your phone and he solved it with a pen on newsprint. The language might change, the references might shift, but the logic remains the same.

It’s a game of empathy. You are trying to get inside the head of the editor. You’re asking, "What did Joel mean by this?" It’s one of the few places left in our culture where we still value the nuance of a single word.

Actionable Steps for New Solvers

- Download the NYT Games App. Yes, it costs money (eventually), but the archive access is worth it. You can go back and solve Mondays from 1996 to build your confidence.

- Learn the "Shortz-isms." Words like AREA, ERIE, ALEE, and ORATE appear constantly because they are vowel-heavy. Memorize them.

- Don't be afraid to Google. Purists will scream, but if you’re stuck on a trivia fact (like a 1920s actor), just look it up. It’s better to finish the puzzle and learn something than to stare at a blank square for three hours and give up.

- Watch "Wordplay." It’s a 2006 documentary about the American Crossword Puzzle Tournament. It’ll make you fall in love with the community.

- Follow the "Wordplay" Column. The NYT publishes a daily blog that explains the theme and the tricky clues for that day's puzzle. It’s like a post-game analysis.

The crossword isn't a test of intelligence. It’s a test of persistence. The more you show up, the more the grid opens up to you. Start small. Mondays only. Before you know it, you'll be complaining about the rebus on a Thursday just like the rest of us.