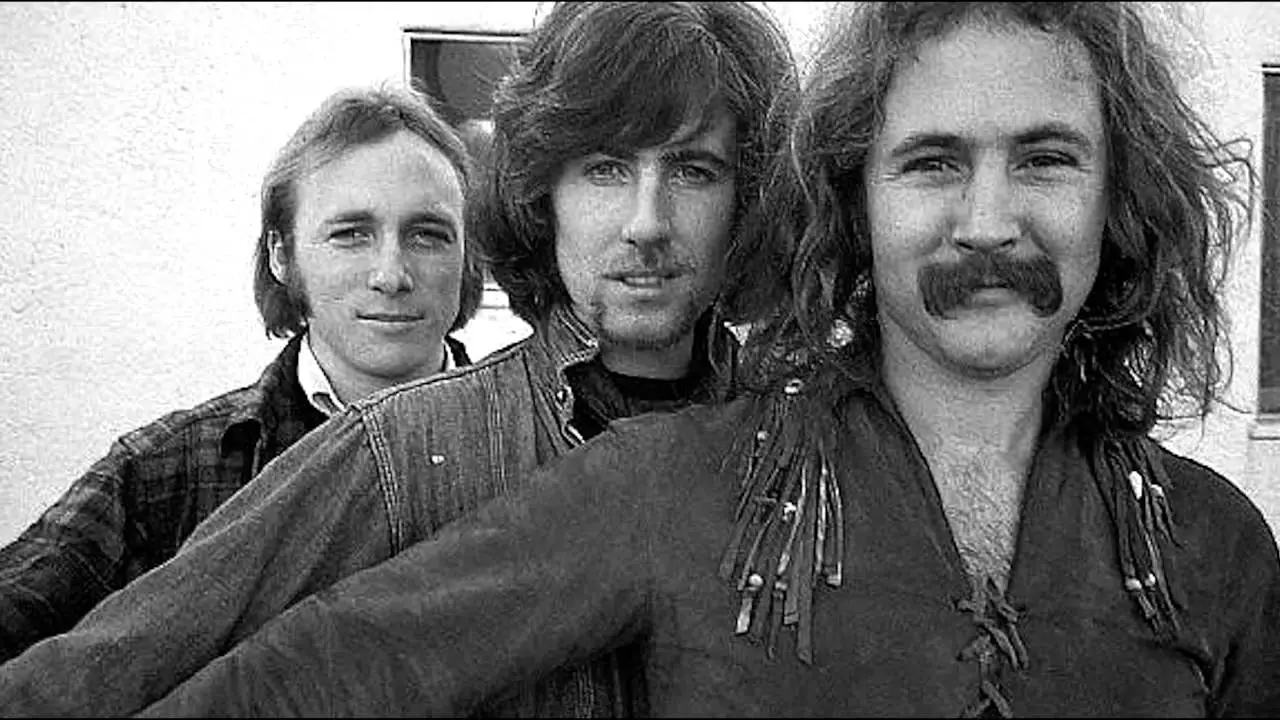

In 1968, three guys stood in a kitchen in Laurel Canyon and sang "You Don't Have to Cry." It took about thirty seconds. By the time the last note faded, the world of folk rock had shifted. David Crosby, Stephen Stills, and Graham Nash didn't just find a harmony; they found a sound that felt like it had existed forever, just waiting for them to uncover it.

Honestly, it’s easy to dismiss Crosby Stills and Nash songs as just "boomer nostalgia" or background music for a coffee shop. But if you actually listen—I mean, really listen—to the architecture of those tracks, you’ll find something much more jagged and strange. These weren't just pretty tunes. They were public breakup letters, political broadsides, and complex musical suites disguised as pop.

The Myth of the "Democratic" Band

One of the biggest misconceptions about their debut album is that it was a group effort in the traditional sense. It wasn't. While the three-part harmonies are the star of the show, Stephen Stills was basically a one-man army in the studio.

✨ Don't miss: Scrat the Ice Age Squirrel: Why a Sabertooth Nut Obsession Changed Animation Forever

His bandmates even nicknamed him "Captain Many Hands." Why? Because Stills played nearly every instrument on that first record. The bass, the organ, the lead guitar—that’s all him. Crosby and Nash mostly just showed up with their acoustic guitars and those otherworldly voices. This dynamic created a weird tension that defined their best work. You had Stills’ rigid, perfectionist musicianship clashing with Crosby’s jazz-influenced, "let it fly" attitude.

"Suite: Judy Blue Eyes" is a Seven-Minute Breakup

Take a look at "Suite: Judy Blue Eyes." Most people know the "de-de-de-de-de" part at the end. It's catchy. But the song is actually a four-part classical suite written by Stills for Judy Collins as their relationship was falling apart.

It’s incredibly raw. He’s basically begging her not to leave while simultaneously acknowledging that they’re doomed. Most bands in 1969 were releasing three-minute radio edits. CSN put out a seven-and-a-half-minute epic that changed its tempo and tuning three times. That kind of risk-taking is why Crosby Stills and Nash songs stuck. They didn't care about the "rules" of the Top 40.

The Hollies' Loss was CSN’s Gain

Graham Nash brought a very different energy. He was coming off a massive run with The Hollies in the UK, but he was bored. He wanted to write "Marrakesh Express," a song about a train ride through Morocco.

The Hollies thought it was trash. They literally rejected it for not being commercial enough. Imagine being the guy who turned down a song that would go on to define a generation. Nash quit the band, moved to LA, and brought those pop sensibilities to Crosby and Stills. He provided the "glue." Without Nash’s knack for a hook, the band might have disappeared into Crosby’s weird tunings and Stills’ ego.

🔗 Read more: The Terrifying Transformation: What Nicolas Cage Actually Did for Longlegs

More Than Just Peace and Love

By the time they added Neil Young and recorded Déjà Vu, the "rosy" feeling of the first album was gone. It was 1970. Things were getting dark.

- David Crosby was grieving the death of his girlfriend, Christine Hinton, who died in a car crash just as sessions began. You can hear it in "Almost Cut My Hair." That's not just a song about long hair; it’s a song about paranoia and grief.

- Graham Nash was living in a domestic bubble with Joni Mitchell, which gave us "Our House," but even that had a shelf life.

- Stephen Stills was still mourning Judy Collins.

The result? An album that felt like a beautiful glass vase that had been cracked and glued back together.

Why the Harmony Worked (The Technical Side)

There's a reason nobody else could quite replicate their sound. It wasn't just that they were good singers. It was the stack.

Usually, in a three-part harmony, you have a clear melody, a high part, and a low part. CSN did something different. Their voices were so close in range and so familiar with one another that they could swap parts mid-phrase. Bill Halverson, their long-time engineer, once noted that they would often record all three voices around a single microphone. They would physically move closer or further from the mic to mix themselves in real-time.

🔗 Read more: Actors from St. Louis MO: Why the Gateway City is Such a Weirdly Huge Pipeline for Hollywood

They weren't just singing notes; they were vibrating at the same frequency.

What You Should Do Next

If you really want to appreciate Crosby Stills and Nash songs, don't just listen to the Greatest Hits.

- Listen to "Wooden Ships" on a good pair of headphones. Focus on the interplay between the lyrics—which are about a nuclear apocalypse—and the breezy, sailing-ship melody. It’s a bizarre contrast that works perfectly.

- Check out the live version of "Helplessly Hoping" from Woodstock. It was only their second gig ever. You can hear the nerves, but when the harmony hits, it’s like a physical force.

- Explore the "Crosby-Nash" duo albums from the mid-70s. Tracks like "Immigration Man" show a different, more experimental side of the group that often gets overshadowed by the big CSNY hits.

The legacy of these songs isn't just about the 60s. It's about how three completely different, often conflicting personalities could occasionally stop fighting long enough to create something that sounded like a single, perfect human voice. That's a miracle in any decade.

Next Steps for Deep Listening:

Start by listening to the 1969 self-titled "Couch Album" from beginning to end. Pay attention to "Guinnevere"—Crosby’s masterpiece in a strange tuning—and see if you can track the three different vocal lines. Then, compare the studio precision of Déjà Vu to the raw, messy energy of their 4 Way Street live album to see which version of the band resonates with you more.