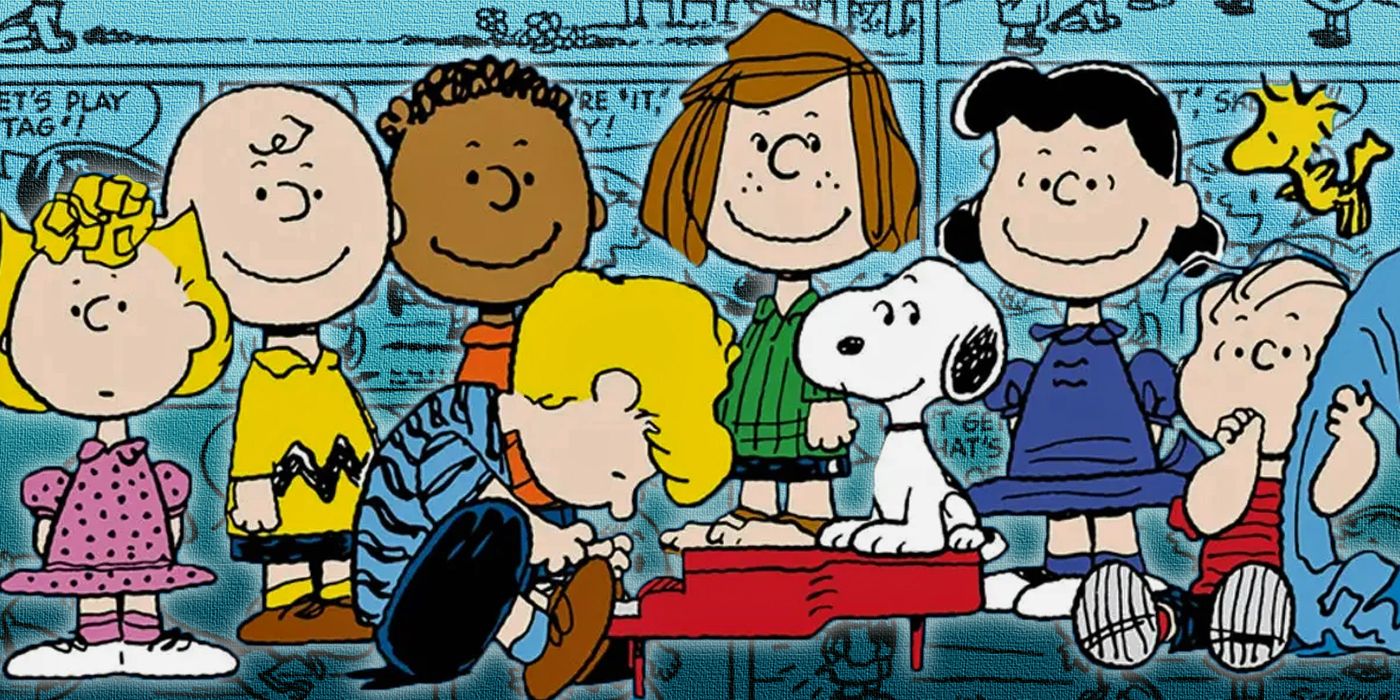

Charles Schulz didn’t just draw circles with ears. He built a psychological map. Honestly, if you look at the comic strip Peanuts characters, you aren't seeing kids; you're seeing a raw, unfiltered look at the human condition that somehow managed to survive fifty years of daily deadlines and a million lunchbox licenses.

It's wild.

💡 You might also like: What Does Dr Doom Look Like: The Truth Under the Mask

Most people think of Snoopy dancing on a doghouse or Charlie Brown missing a kick, but the strip was actually pretty dark. Schulz once said that "happiness is a warm puppy," but he also spent decades exploring unrequited love, clinical depression, and the sheer existential dread of being alive. It’s why we’re still talking about them in 2026. They feel real.

The Charlie Brown Effect: Why We Love a Loser

Charlie Brown is the anchor. He’s the "lovable loser," sure, but that’s a superficial take. He’s actually a study in resilience. No matter how many times Lucy pulls that football away—a gag that appeared for the first time in 1952, though it was actually Violet who pulled it first—he comes back.

He’s the personification of the "Good Grief" catchphrase.

Have you ever noticed how rarely he actually wins? Schulz was adamant about this. He felt that there was nothing funny about a winner. In his view, most of us feel like losers most of the time, even when we aren't. Charlie Brown isn't just a character; he's the manifestation of our own insecurities. He worries about the "Tree-Eating Kite." He worries about his "wishy-washy" nature. He’s the patron saint of anyone who’s ever felt like they didn't belong at the party.

Lucy Van Pelt and the Art of the Fussbudget

Then there’s Lucy. Every group of friends has a Lucy. She’s loud, she’s crabby, and she’s the neighborhood's most unlicensed psychiatrist. That five-cent psychiatric booth is iconic, but the advice she gives is usually terrible. "Snap out of it!" is her default.

But here’s the thing about the comic strip Peanuts characters: they have layers. Lucy isn't just a bully. She’s also someone who suffers from her own version of unrequited love. She spends half her life leaning against Schroeder’s piano, practically begging for a glance, while he just keeps playing Beethoven. She’s powerful and fragile all at once. It’s a messy, human contradiction.

Snoopy: The Dog Who Refused to Be a Dog

If Charlie Brown is the ID, Snoopy is the Ego. He’s the breakout star for a reason.

Originally, back in 1950, Snoopy was just a regular dog who walked on four legs. He didn't talk—well, he never "talked," he thought in thought bubbles. But as the years went on, he became bipedal and started inhabiting these elaborate fantasy worlds. He’s a World War I Flying Ace. He’s Joe Cool. He’s a world-famous novelist writing the same first line over and over: "It was a dark and stormy night."

Snoopy is the ultimate escapist.

He lives in a world of his own making because the real world—where he's just a dog who has to wait for a "round-headed kid" to bring him dinner—is too boring. He’s the antithesis of Charlie Brown’s grounded, heavy reality. Snoopy is pure, unadulterated imagination. He's also kind of a jerk sometimes, which makes him way more interesting than your average cartoon pet.

Linus and the Security Blanket

Linus Van Pelt is probably the most intellectual kid in the history of media. He quotes the Bible, discusses philosophy, and yet... he can't let go of that blue blanket. Schulz actually popularized the term "security blanket." Before Linus, that wasn't really a common phrase in the American lexicon.

It’s a brilliant juxtaposition.

You have this kid who can explain the meaning of Christmas or dissect a complex theological point, but he’s terrified of his own shadow without a piece of flannel. It shows that intelligence doesn't protect you from anxiety. We all have blankets. For some of us, it’s a phone. For others, it’s a specific routine. Linus just carries his out in the open.

💡 You might also like: Alice Brock and Alice's Restaurant: What Really Happened at the Church

The Supporting Cast: More Than Just Background

The "Peanuts" universe is surprisingly deep once you get past the "Big Four."

- Sally Brown: She represents the frustration of bureaucracy. She hates school with a passion that borders on the religious. Her "philosophy" is usually just an excuse to avoid work.

- Peppermint Patty: A tomboy who lives in a different neighborhood, she’s the one who constantly calls Charlie Brown "Chuck." She’s also a bit of a tragic figure, struggling in school (D-minus is her specialty) and living in a single-parent household, which was a big deal for a comic strip in the 60s.

- Marcie: The "Sir" calling, highly intelligent sidekick. She’s the only one who really sees Patty for who she is, even if Patty is too oblivious to realize Marcie is the brains of the operation.

- Franklin: Introduced in 1968 after the death of Martin Luther King Jr., Franklin was a quiet but massive statement. Schulz fought his syndicate to keep Franklin in the strip, insisting that he belonged there as an equal to the other kids.

Why the Strip Stopped (But Didn't Really)

Charles Schulz drew every single frame of Peanuts himself for nearly 50 years. No ghosts. No assistants. He had a hand tremor toward the end, which you can actually see in the lines of the later strips—they’re a bit shakier, a bit more fragile.

He died in 2000, the night before the final Sunday strip was published.

It was an ending so poetic you couldn't write it in a movie. But the comic strip Peanuts characters didn't die with him. They’re stuck in a perpetual childhood, forever leaning against that brick wall, forever failing to fly that kite. We keep returning to them because their problems are our problems. Adult life is just a series of "Good Grief" moments, and we’re all just looking for our own version of a warm puppy or a Beethoven sonata to get us through the day.

If you want to really understand the impact of these characters, stop looking at the merchandise. Forget the MetLife commercials or the Hallmark cards. Go back and read the strips from the 1960s. Look at the way Schulz used white space. Look at the expressions. You’ll realize it isn't a kid’s strip. It’s a manual for how to survive being human.

How to Engage with Peanuts Today:

- Read the Fantagraphics Collections: They’ve published the "Complete Peanuts," and seeing the evolution of the art style from the 50s to the 90s is a masterclass in character design.

- Watch the Specials (Beyond Christmas): "A Charlie Brown Christmas" is the GOAT, but "It's the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown" captures the essence of Linus's faith better than almost anything else.

- Study the Minimalism: If you’re a creator, look at how much emotion Schulz conveys with just two dots for eyes and a curved line for a mouth. It’s a lesson in "less is more."

The brilliance of Peanuts is that it never gave us a happy ending. Charlie Brown never kicks the ball. And honestly? We wouldn't want him to. Because if he kicks it, the story is over. The struggle is the point. That’s the real secret of the comic strip Peanuts characters—they teach us that it’s okay to fail, as long as you show up again tomorrow.