King Hu changed everything in 1966. Before Come Drink with Me, the wuxia genre was basically just a collection of stagey, clunky operas caught on film. People weren't really moving; they were posing. Then came Cheng Pei-pei. She stepped into the role of Golden Swallow, and suddenly, the "knight-errant" wasn't just some guy in a robe—it was a woman who could dismantle a room full of thugs without breaking a sweat. It’s hard to overstate how much this movie influenced every single martial arts film you’ve ever loved, from Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon to John Wick.

Honestly, it's the rhythm. King Hu wasn't just a director; he was a choreographer of space. He understood that a fight scene shouldn't just be about who hits whom. It’s about the tension before the first punch. It’s about the silence.

The Story Behind the Come Drink with Me Movie

The plot is deceptively simple. A group of bandits kidnaps a governor’s son. They want to trade him for their incarcerated leader. The government sends in their best agent, Golden Swallow. The twist? Golden Swallow is the kidnapped man's sister. She’s lethal, precise, and disguised as a man—at least initially. She ends up at a rural inn, which serves as the stage for one of the most iconic standoffs in cinema history.

This isn't your typical 1960s action flick. Hu brings a scholarly, almost Zen-like approach to the violence. You’ve got the Drunken Cat, a beggar who is secretly a kung fu master, acting as a sort of guardian angel for Golden Swallow. Their dynamic isn't built on romance. It's built on respect and the passing of martial knowledge.

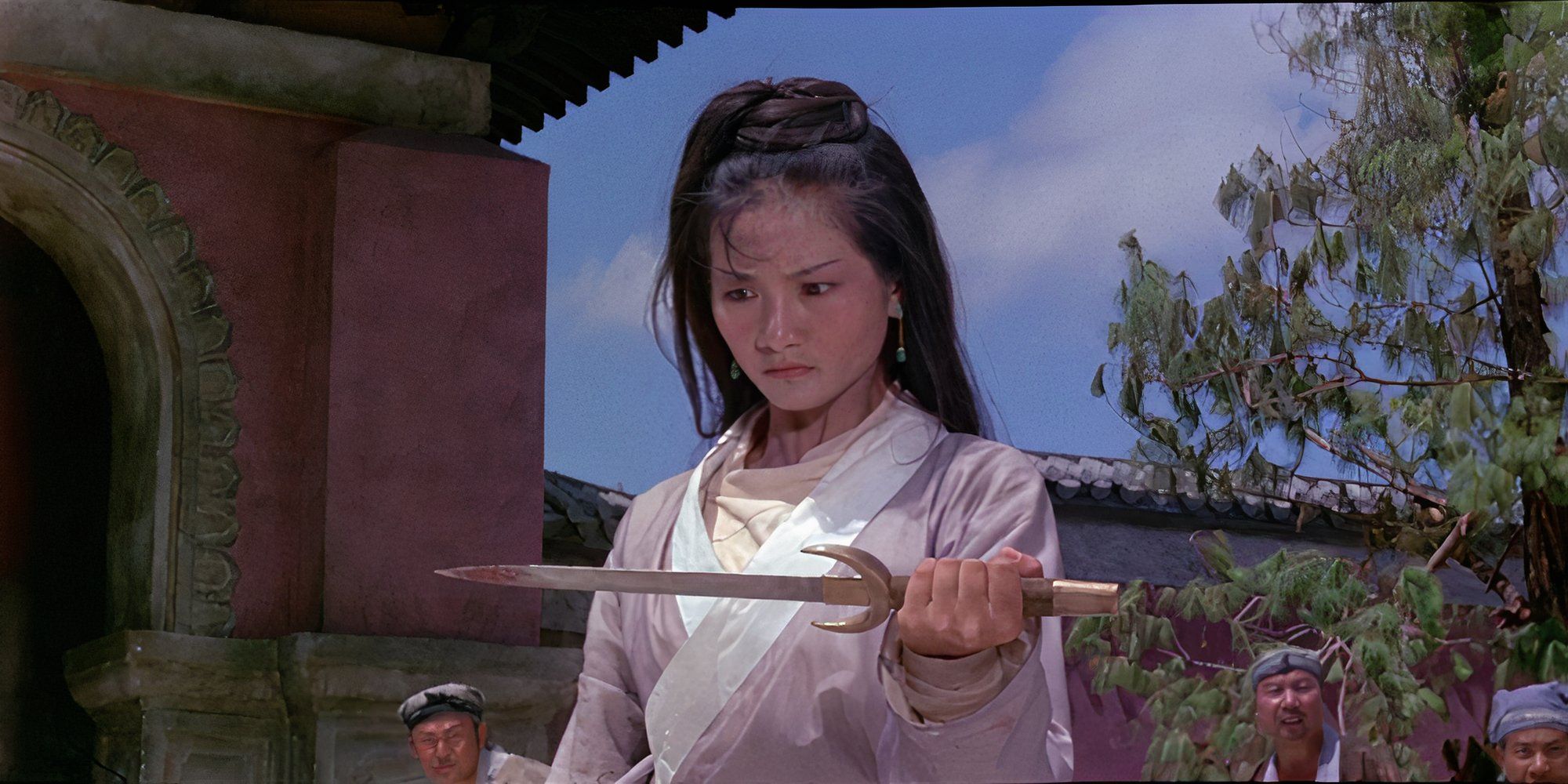

Why Cheng Pei-pei is the Queen

Cheng Pei-pei was only 19 when she filmed this. She wasn't even a trained martial artist; she was a dancer. You can see it in her movements. She doesn't lumber. She glides. When she’s at the inn, fending off coins and bowls thrown at her by the bandits, it’s a ballet. King Hu famously used his background in Peking Opera to style the movements, focusing on grace rather than brute force.

This decision was revolutionary. By casting a dancer, Hu proved that cinematic martial arts are about the image of power, not just the application of it. Cheng’s piercing gaze became the blueprint for the female wuxia hero. Without Golden Swallow, there is no Jen Yu or Yu Shu Lien in Ang Lee's masterpieces.

📖 Related: Big Brother 27 Morgan: What Really Happened Behind the Scenes

The Inn as a Battlefield

Most of the first half of the Come Drink with Me movie takes place inside a single tavern. This is a classic trope now, but Hu perfected it here. The geography of the room matters. You know exactly where every bandit is sitting. You feel the walls closing in as the tension ramps up.

Hu used the camera to create a sense of frantic energy. He used "shaky cam" and quick cuts long before they became the annoying staples of modern blockbusters. But here, they serve a purpose. They mimic the disorientation of a real brawl.

The sound design is also strangely ahead of its time. The clinking of wine cups, the thud of a staff on wood, the sudden whistle of a flying dagger—it’s all hyper-real. It makes the world feel lived-in. This wasn't a shiny, plastic set; it felt like a dusty, dangerous corner of the Ming Dynasty.

The Drunken Master Archetype

We have to talk about Fan Mei-sheng and the Drunken Cat. While Jackie Chan would later turn "Drunken Fist" into a global comedy brand, Come Drink with Me treated the trope with a bit more mysticism. The "beggar master" is a staple of Chinese folklore, representing the idea that true power is often hidden behind a humble or even ridiculous exterior.

In this film, the Drunken Cat provides the moral compass. He’s the one who navigates the complex politics between the bandits and the monks. Yeah, there are evil monks. It adds a layer of religious and social critique that most action movies of the era completely ignored.

👉 See also: The Lil Wayne Tracklist for Tha Carter 3: What Most People Get Wrong

Breaking the Shaw Brothers Mold

At the time, the Shaw Brothers Studio was an assembly line. They cranked out movies like cars. Most directors just followed the template. King Hu hated the template. He obsessed over historical accuracy—or at least a very specific, stylized version of it. He spent ages on costumes and lighting.

- Lighting: He used natural light whenever possible, creating deep shadows that felt noir-ish.

- Editing: He pioneered a "glance" editing style where the action is dictated by where the characters are looking.

- Pacing: He wasn't afraid to let a scene breathe for five minutes before a ten-second burst of violence.

This perfectionism eventually led to a falling out with the studio. Hu moved to Taiwan to make Dragon Inn, but Come Drink with Me remains his most accessible work. It’s the bridge between the old world of filmed theater and the new world of kinetic action.

Influence on Modern Cinema

If you watch Kill Bill, you’re watching a love letter to this movie. Quentin Tarantino has been vocal about his obsession with the Shaw Brothers era, and the DNA of Golden Swallow is all over the character of The Bride. The idea of the "one versus many" in a confined space is a direct descendant of the inn sequence.

But it’s not just the West. Hong Kong cinema spent the next thirty years trying to replicate the "King Hu look." The 1990s wuxia revival, led by Tsui Hark, owes everything to this 1966 classic. Even the "wire-fu" that became famous in The Matrix has its roots in the stylized leaps and bounds Hu choreographed here, even if he used more primitive methods like trampolines and clever camera angles.

Is it still "watchable" today?

Totally. Some 60s movies feel like homework. This doesn't. The colors are vibrant (especially if you find the 88 Films or Celestial Pictures restorations). The stakes feel real because the characters aren't invincible. Golden Swallow actually gets hurt. She makes mistakes. She needs help. That vulnerability makes her eventual victory feel earned rather than inevitable.

✨ Don't miss: Songs by Tyler Childers: What Most People Get Wrong

One thing that might surprise modern viewers is the lack of "powers." There are no CGI fireballs. It’s all physics, even if it’s a slightly exaggerated version of physics. When someone jumps onto a roof, they look like they’re actually putting effort into it.

How to Experience the Legacy of Come Drink with Me

If you're looking to dive into this era of cinema, don't just stop at the credits. Understanding the context makes the film even better.

Track down the restoration.

Don't watch a grainy bootleg on YouTube. The cinematography by Tadashi Nishimoto is gorgeous and deserves a high-definition screen. The way he uses the widescreen framing is a masterclass in composition.

Watch the "sequel" (sort of).

Cheng Pei-pei returned as Golden Swallow in a film actually titled Golden Swallow (1968), directed by Chang Cheh. It’s a very different vibe—much bloodier and more "masculine"—but it shows how the character evolved into a legend.

Look for the visual echoes.

Next time you watch a movie where a lone warrior enters a bar/tavern/saloon, pay attention to how the director introduces the threats. You'll start seeing King Hu's fingerprints everywhere. From the way the hat shadows the eyes to the slow sip of tea before the swords are drawn, it’s all there.

Explore King Hu’s later work.

If this movie clicks for you, A Touch of Zen is the next logical step. It’s longer, more philosophical, and features some of the most beautiful forest combat ever filmed.

The Come Drink with Me movie isn't just a piece of history; it’s a living textbook on how to tell a story through movement. It's about the dignity of the warrior and the artistry of the fight. It reminds us that before there were superheroes, there were knights-errant, and sometimes, the deadliest knight in the room was the one holding the bamboo flute.