You’ve seen them in your high school history books. Usually, it’s a giant bear wearing a ushanka or a tall, lanky guy in striped pants pointing a finger across a map of Europe. We call them Cold War political cartoons, but honestly, they were more like the original memes—only with much higher stakes. They weren't just "funny drawings." They were psychological warfare.

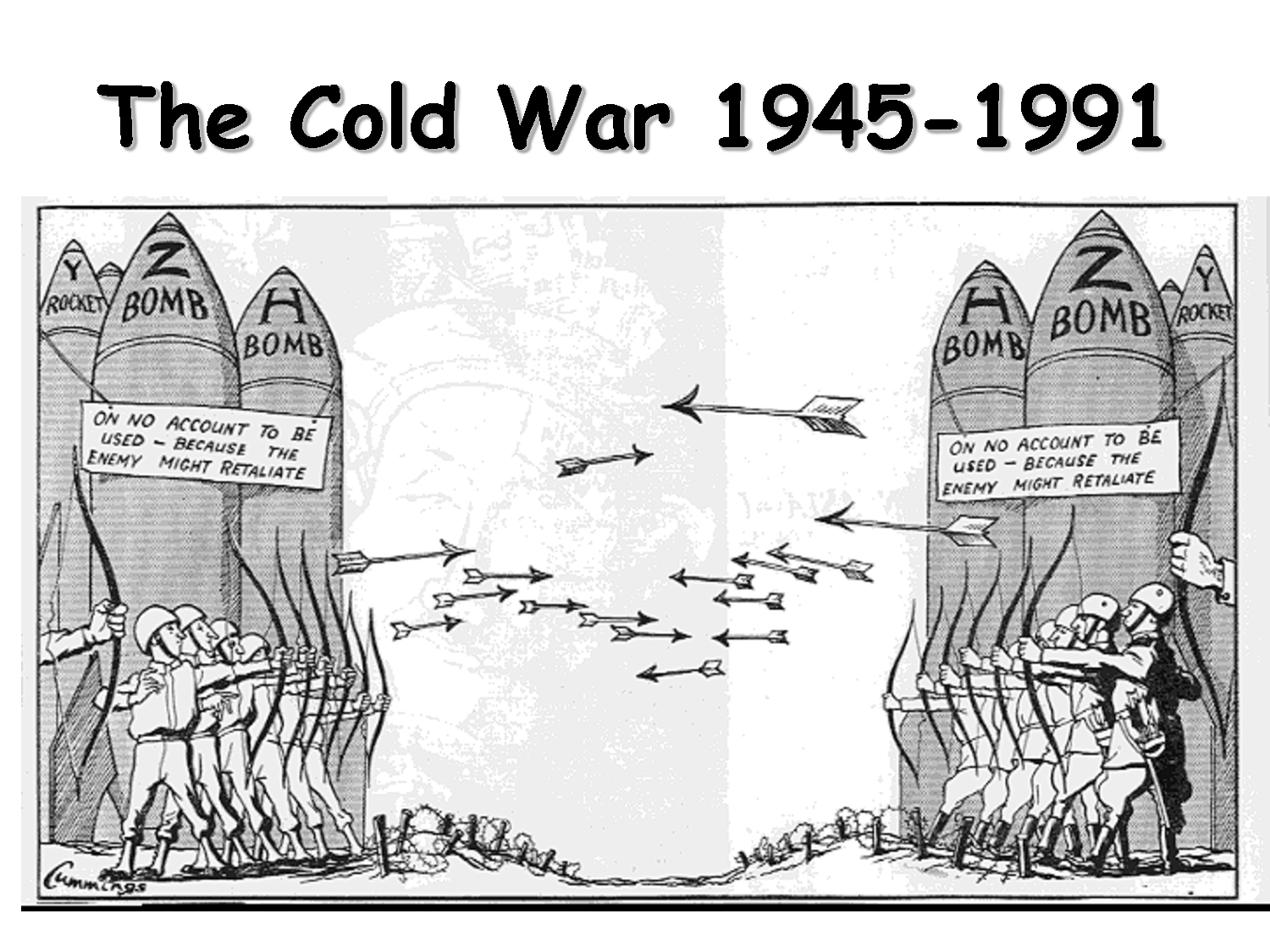

During the forty-plus years of the standoff between the United States and the Soviet Union, these sketches did the heavy lifting of explaining complex geopolitics to a terrified public. Think about it. How do you explain "Mutually Assured Destruction" to a suburban family in 1955? You don't give them a lecture on game theory. You draw two guys sitting on crates of TNT, holding matches. It’s simple. It’s visceral. And it worked.

The Men Behind the Ink

Herb Block, famously known as Herblock, basically defined the American perspective for decades at The Washington Post. He’s actually the guy who coined the term "McCarthyism." Can you imagine? One cartoonist created the word we still use to describe political witch hunts. He drew Joseph McCarthy as a literal mud-slinger, dragging the dignity of the Senate through the gutter. It was brutal.

On the other side of the pond, you had guys like Illingworth and David Low. Low was a genius at capturing the sheer exhaustion of post-war Britain. He didn't just draw politicians; he drew the weight of the world on their shoulders.

Then there’s the Soviet stuff. If you look at Krokodil, the USSR’s satirical magazine, the vibe changes completely. It wasn't about "free speech" or "speaking truth to power" in the way Westerners think. It was state-sponsored. It was propaganda disguised as humor. They drew Uncle Sam as a bloated capitalist with dollar signs for eyes, usually stepping on the necks of workers in the "Third World." It’s fascinating because, while the art was often incredible, the message was strictly controlled by the Central Committee. No one was drawing Khrushchev looking like a fool unless they wanted a one-way ticket to a labor camp.

The Nuclear Anxiety in Pen and Ink

The 1950s was a weird time. People were building fallout shelters in their backyards. Naturally, Cold War political cartoons reflected this collective panic.

🔗 Read more: St. Joseph MO Weather Forecast: What Most People Get Wrong About Northwest Missouri Winters

One of the most famous images from this era is the "The Brink" by Herblock. It shows John Foster Dulles (Eisenhower's Secretary of State) leading the American people to the very edge of a crumbling cliff. It captured the "brinkmanship" policy perfectly. No long-winded essays needed. Just a man looking into an abyss.

Sometimes the cartoons were darker. There's a famous one showing the world as a giant bomb, with two world leaders fighting over who gets to hold the fuse. It highlights a nuance that gets lost in history books today: many people didn't just fear the "other side." They feared their own leaders' incompetence.

Why We Still Care About These Drawings

Why bother looking at these old sketches now? Because we’re seeing the same tropes come back. Today’s digital illustrators and meme-makers are using the same visual shorthand that was perfected between 1947 and 1991. The "Russian Bear" hasn't gone anywhere. The personification of national interests as singular, often stubborn characters is a tool that never gets old.

The Cuban Missile Crisis: A Masterclass in Visual Tension

In October 1962, the world almost ended. For thirteen days, everyone held their breath. The cartoons from that specific month are some of the most intense ever created.

There's a specific cartoon by British artist Leslie Illingworth called "The Finger on the Button." It shows Kennedy and Khrushchev arm-wrestling. They’re both sweating. They’re sitting on desks that are actually nuclear missiles. It’s the ultimate representation of the Cold War. It shows that neither side really wanted to push the button, but neither could afford to look weak. It captures the stalemate better than any 500-page biography of JFK ever could.

💡 You might also like: Snow This Weekend Boston: Why the Forecast Is Making Meteorologists Nervous

It’s worth noting that these cartoons didn't just reflect public opinion; they shaped it. By making the "enemy" look ridiculous or monstrous, they helped justify massive military spending. When you see the Soviet Union depicted as a literal octopus wrapping its tentacles around the globe, it’s a lot easier to agree with a massive defense budget.

The Evolution of the Style

Early Cold War art was very "grand." It felt like epic poetry. Lots of classical metaphors. You'd see Liberty or Justice looking distraught in a toga.

But as the 60s and 70s rolled around, things got grittier. The Vietnam War changed everything. Cartoonists started turning their pens on their own government with a ferocity we hadn't seen before. The "enemy" wasn't just a guy in Moscow anymore; sometimes the enemy was the policy coming out of the Oval Office.

- 1940s/50s: High contrast, clear "Good vs. Evil" narratives, focus on Europe.

- 1960s: More cynical, focus on the "space race" and nuclear buildup.

- 1970s/80s: Focus on Détente (the easing of tensions), then a sharp return to "Evil Empire" rhetoric under Reagan.

Misconceptions About Satire

A lot of people think these cartoons were always popular. Not true. Cartoonists were regularly threatened. Herblock was hated by many in the Nixon administration. Satire is a dangerous game when the world is on a hair-trigger.

Also, we tend to think of these as "American" or "Russian," but the cartoons coming out of "Non-Aligned" countries like India or Yugoslavia are wild. They viewed both superpowers as two bullies fighting in a China shop. Those perspectives are often ignored in Western textbooks, but they offer a much more objective look at how the Cold War felt to the rest of the planet.

📖 Related: Removing the Department of Education: What Really Happened with the Plan to Shutter the Agency

How to Analyze a Political Cartoon Yourself

If you’re looking at Cold War political cartoons for a project or just because you’re a history nerd, don't just look at the faces. Look at the symbols.

- Check the labels. Cartoonists in the mid-century loved labeling everything. "Public Opinion," "The Iron Curtain," "Atomic Secrets."

- Look for the scale. Is one character much larger than the rest? That’s not an accident. It represents power or bullying.

- Identify the irony. Usually, the caption says one thing, but the drawing shows the opposite.

Honestly, the best way to learn is to just go to the Library of Congress digital archives. They have thousands of Herblock's original sketches. You can see his pencil marks. You can see where he erased things. It makes the history feel... real. Not like something that happened in a vacuum, but something that was being commented on in real-time by a guy with a deadline and a bottle of ink.

What You Should Do Next

History isn't just about dates and treaties. It’s about how people felt, and nothing captures feeling better than a biting piece of satire.

If you want to get serious about this, start by looking up the "Herblock's History" exhibit online. It’s a great jumping-off point. After that, find a cartoon from the 1980s—maybe something about the "Star Wars" (Strategic Defense Initiative) program—and compare it to a modern meme about current global tensions. You'll be shocked at how little the "visual language" of power has changed.

The next step? Pick a major event—like the fall of the Berlin Wall—and find three different cartoons about it: one from the US, one from the UK, and one from a Soviet-aligned country. Seeing those three perspectives side-by-side will give you a better education on the end of the 20th century than any documentary could.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs:

- Visit the Library of Congress: Search their digital collections for "Herbert Block" to see high-resolution scans of original Cold War drafts.

- Check out 'Krokodil' archives: Look for English translations of Soviet-era satire to understand the "other side's" propaganda machine.

- Analyze the 'Visual Metaphors': Create a list of recurring symbols (the bear, the eagle, the bomb, the wall) to see how they evolved from 1945 to 1991.

- Compare and Contrast: Find a cartoon from the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis and compare it to a modern editorial cartoon about nuclear proliferation today.

History is still being drawn every day. Understanding the pens of the past helps you read the headlines of the present.