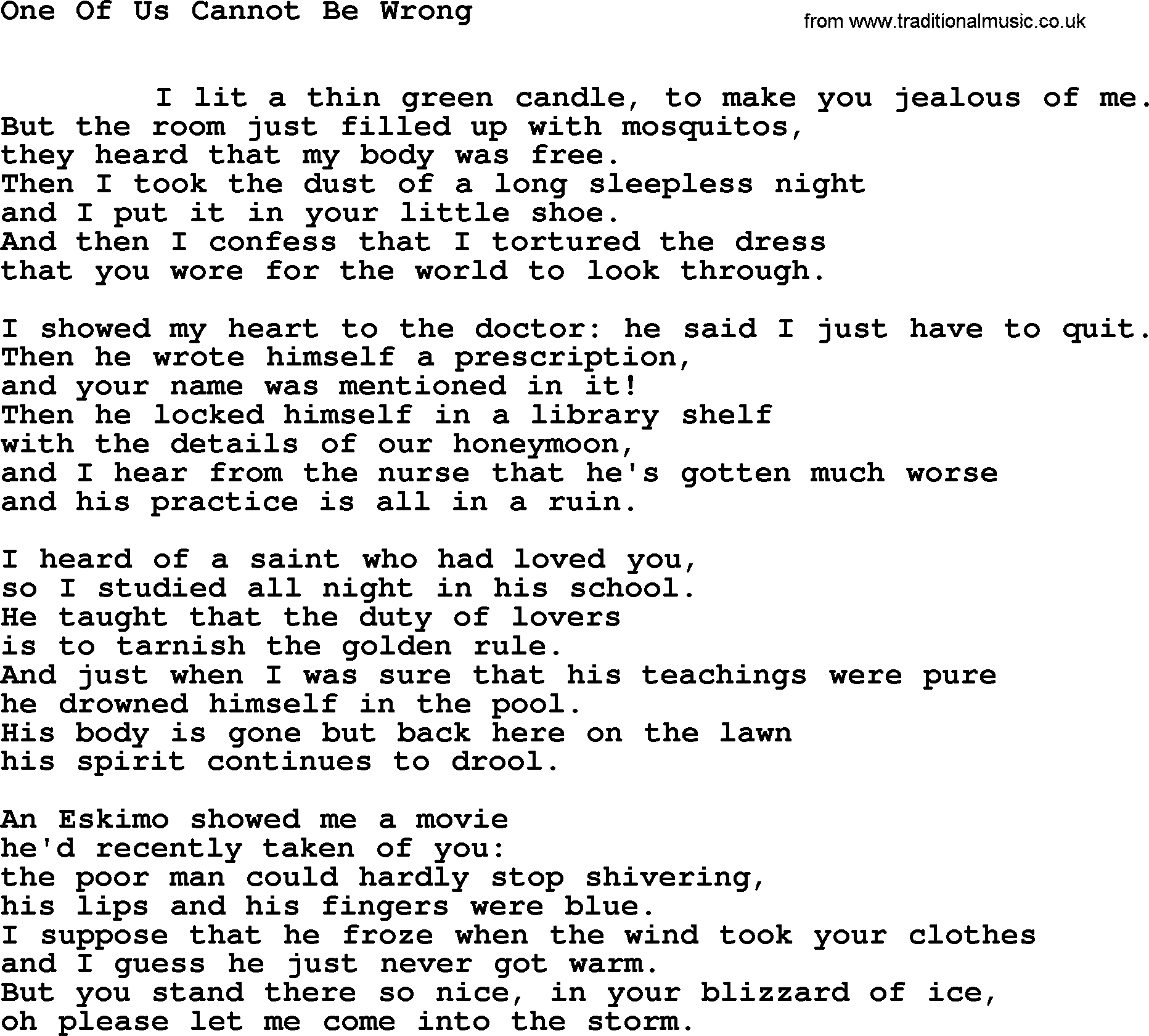

Leonard Cohen was a man who knew how to suffer with style. When you sit down and really chew on the Cohen lyrics One Of Us Cannot Be Wrong, you aren’t just listening to a folk song from 1967. You are basically eavesdropping on a nervous breakdown set to a waltz. It is messy. It is loud. It is honestly one of the most desperate things ever recorded on vinyl.

The song closes out his debut album, Songs of Leonard Cohen. Most people remember that record for "Suzanne" or "Hey, That’s No Way to Say Goodbye." Those are the pretty ones. "One Of Us Cannot Be Wrong" is the one that screams at you from the corner of a dark room. It starts with a dusty, acoustic modesty and ends with Cohen literally howling like a wounded animal. It’s a trip.

The Brutal Story Behind the Song

We have to talk about the context because Leonard didn’t just pull these images out of thin air. He was a poet first, a novelist second, and a singer third—maybe even fourth depending on who you ask about his vocal range. This track was born out of a period of intense, almost pathological jealousy. Cohen was living on the Greek island of Hydra, a place that sounds idyllic but was actually a pressure cooker for expatriate drama.

He was obsessed with a woman who had moved on. That's the core of it.

The song is structured as a series of vignettes about people who tried to "solve" the problem of love or desire and failed miserably. You’ve got the man writing on the paper, the guy with the green syringe, and the Eskimo. Each one is a surrogate for Cohen’s own frustration. He’s looking at these other "losers" in the game of love and saying, "Look, if they are crazy, and I'm doing the same thing, then one of us has to be right." But the irony is thick. He knows they are all doomed.

Dissecting the Imagery

Let’s look at that first verse. He talks about a man who writes "your name" on the "ice and snow." It’s such a futile image. Writing on ice? It’s going to melt. It’s temporary. Then the guy goes to the "center of the dark" and waits for his "breath to go." This isn't a metaphor for a bad breakup. This is a metaphor for total ego death.

✨ Don't miss: Why the Black Female Talk Show Still Rules Daytime TV

Then we get the famous "green syringe" line. This has sparked decades of debate among fans. Is it about heroin? Is it about a literal doctor? Honestly, knowing Cohen’s history with depression and the pharmaceutical "solutions" of the 60s, it’s likely a bit of both. He mentions a doctor who "showed me a way to get high." But the kicker is that the doctor ends up "drifting" himself. Even the healers are broken. That is the ultimate Cohen move: showing that the people we look to for guidance are just as lost in the woods as we are.

Why the Vocals Change Everything

You can't just read the Cohen lyrics One Of Us Cannot Be Wrong and get the full picture. You have to hear the descent.

The song starts in a very controlled, almost monotone baritone. It’s the voice of a man who thinks he has a handle on his grief. But as the verses progress, the tempo doesn't really change, yet the intensity boils over. By the time he gets to the part about the Eskimo—who showed him a "movie" that proved he was "wrong"—the song dissolves.

The ending is a cacophony. Cohen starts whistling. Then he starts screaming. It’s a high-pitched, jagged sound that stands in total contrast to the "Golden Voice" he became famous for in the 80s and 90s. It’s ugly. It’s supposed to be. It represents the moment where language fails. When the lyrics aren't enough to express the pain of being replaced, you just have to make noise.

The Mystery of the Eskimo

What is up with the Eskimo? Seriously.

"I heard of a saint who had loved you / So I studied all night in his school / He taught that the duty of lovers / Is to tarnish the golden rule."

That stanza is a masterclass in subverting expectations. We usually think of saints as people who elevate love. Cohen’s saint teaches that lovers must break the rules. They must be selfish. They must be cruel. Then he shifts to the Eskimo who is "too light for the 20th century." This is likely a reference to a more "primitive" or "pure" state of being that can't survive in the modern, cynical world Cohen inhabited in Montreal or New York.

When the Eskimo sleeps with his "wife" (or the subject's wife), it’s presented as a moment of clarity. The narrator realizes his own jealousy is a cage. He’s "wrong" because he’s trying to possess something that can't be owned.

Cultural Impact and Covers

A lot of people actually came to this song through covers before they ever heard Leonard's version. Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds did a version that is predictably dark. Harvey Milk did a sludge-metal version that leans into the screaming. But there’s something about the original's fragility that stays with you.

When Beck covered it for the "Record Club" series, he kept that lo-fi, crumbling aesthetic. It works because the song is inherently unstable. It’s a document of a man falling apart in real-time.

🔗 Read more: Katy Perry Last Friday Night: Why We Are Still Obsessing Over This Song 15 Years Later

The Technical Brilliance of the Lyrics

If we look at the meter, Cohen is using a standard folk-waltz $3/4$ time signature. It’s a "lullaby" structure. Using a lullaby to describe a suicidal level of devotion is a brilliant bit of cognitive dissonance. It makes the listener feel safe right before the rug is pulled out.

The rhyme scheme is also deceptively simple.

- You

- School

- Lovers

- Rule

It’s the kind of writing a teenager might do, but because it’s Cohen, it’s infused with this heavy, liturgical weight. He’s using the language of the Bible and the language of the gutter at the exact same time.

What Most People Get Wrong

People often think this is a song about "winning" an argument. They see the title "One Of Us Cannot Be Wrong" and think it’s a flex. It’s the opposite. It’s a confession of total defeat.

The narrator is saying, "Either you are a monster for leaving me, or I am a lunatic for caring this much. Since you seem fine, I must be the one who is wrong." It’s self-immolation. It’s not a victory lap. It’s a man standing in the ruins of a relationship, trying to find a logical explanation for why his heart feels like it’s been put through a woodchipper.

👉 See also: Why Grinch Songs From Movie Versions Still Get Stuck In Your Head Every December

Final Insights on the Cohen Legacy

Leonard Cohen didn't write songs for the radio. He wrote them because he had to get the "demons" out of his head and onto the page. This track is the blueprint for the "sad boy" trope in indie music, but it has a depth that most modern imitators lack. It’s not just "I’m sad"; it’s "I have explored every philosophical and chemical avenue to stop being sad, and I have found that pain is the only truth left."

If you are looking to understand the Cohen lyrics One Of Us Cannot Be Wrong on a deeper level, you have to stop looking for a happy ending. There isn't one. There’s just the whistling at the end of the track, fading into the hiss of the tape.

Actionable Steps for the Deep Diver

To truly appreciate the nuances of this track, try these specific listening and reading exercises:

- Listen to the Mono Mix: If you can find the original mono pressings of Songs of Leonard Cohen, the vocals on "One Of Us Cannot Be Wrong" are much more "in your face." The separation in the stereo mix can sometimes dilute the raw power of the final scream.

- Compare with "Dress Rehearsal Rag": This is another Cohen track from the same era that deals with similar themes of suicide and despair. Comparing the two shows how he used different characters to express the same internal struggle.

- Read "Beautiful Losers": This was the novel Cohen wrote just before recording this album. It’s dense, erotic, and borderline unreadable at times, but it contains the same fever-dream energy found in the song's lyrics.

- Trace the Biblical References: Look up the "Golden Rule" and the concept of "Saints" in the context of the 1960s counter-culture. Cohen was blending his Jewish heritage with a burgeoning interest in Zen Buddhism and Catholic hagiography, and it’s all buried in these verses.

There is no "correct" way to interpret the song, but there is a "correct" way to feel it. You have to let it be uncomfortable. You have to let the screaming happen. Only then do you really get what Leonard was trying to tell us.