Honestly, it’s getting harder to find something actually worth watching. You scroll for forty-five minutes, past the neon-colored thumbnails and the "Trending Now" shows that everyone forgets by Tuesday, only to realize you’re just bored. That’s usually when people start drifting back toward classic movies and tv. There’s a reason for it. It isn’t just about nostalgia or your parents telling you that "they don’t make ‘em like they used to." They actually don't. The pacing was different, the stakes felt heavier, and actors had to do more than just stand in front of a green screen while a post-production team in Vancouver figured out the lighting.

Quality matters.

When we talk about the staying power of things like Casablanca or The Twilight Zone, we're talking about a level of craft that feels almost extinct in the era of "content" creation. Content is a commodity; art is a legacy. Most modern streaming shows are designed to be "bingeable," which is basically code for "addictive enough that you don't turn it off, but not meaningful enough that you have to stop and think." Classic movies and tv weren't built for the skip-intro button. They were built for the theater and the living room, places where you actually sat still.

The Myth of the "Slow" Classic

One of the biggest complaints you’ll hear from younger viewers is that old stuff is "too slow." It’s a common critique, but it’s mostly a misunderstanding of how tension works. Take a look at Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window. It’s basically one guy sitting in a chair looking out a window for two hours. On paper, that sounds like a snooze fest. In reality, it’s a masterclass in voyeurism and mounting dread. Hitchcock doesn't need a jump scare every eight minutes to keep you engaged because he understands the psychology of the audience.

Modern editing has ruined our attention spans. The average shot length in a contemporary action movie is about two to three seconds. In the Golden Age of Hollywood, directors like Orson Welles or John Ford would let a shot breathe for thirty seconds, a minute, or even longer. This wasn't because they were lazy. It was because they wanted you to look at the frame. They wanted you to see the dust in the air, the sweat on the actor’s brow, and the way the shadows fell across the room.

If you think The Godfather is slow, you’re missing the point of the dinner scenes. Those long pauses aren't empty space; they are filled with the weight of what isn't being said. That’s the nuance that gets lost when you’re editing for a TikTok-generation brain.

📖 Related: The A Wrinkle in Time Cast: Why This Massive Star Power Didn't Save the Movie

Why Black and White is a Superpower

There is this weird bias that black and white is "primitive." That’s wild. If anything, shooting in monochrome required a much higher level of technical skill. When you take away color, you lose the ability to use a bright red dress or a blue sky to guide the viewer’s eye. You have to rely entirely on contrast, texture, and composition.

Director of photography Gregg Toland, who worked on Citizen Kane, used "deep focus" to keep everything in the frame sharp, from the foreground to the background. This forced the audience to choose where to look. It made the world feel massive and oppressive. Film noir, like The Big Sleep or Double Indemnity, used harsh lighting to create "chiaroscuro" effects—basically using shadows as a character. You can’t get that same mood from a digital sensor that’s been color-graded to look like a lukewarm sunset.

The TV Revolution Didn't Start with HBO

We like to think that "Prestige TV" started with The Sopranos or The Wire. Those shows are incredible, don't get me wrong. But the DNA for complex, adult storytelling was already there in the 1950s and 60s. Shows like Playhouse 90 were essentially live theater broadcast into homes. You had writers like Rod Serling and Paddy Chayefsky tackling racism, corporate greed, and the existential dread of the Cold War.

The Twilight Zone is the gold standard here. Serling was frustrated by network censors who wouldn't let him write about controversial social issues in a realistic setting. His solution? Put the story on Mars. Or in a parallel dimension. By using sci-fi and fantasy as a "Trojan Horse," he was able to discuss the most pressing issues of the day without the sponsors freaking out. "The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street" is still the most accurate depiction of how quickly a neighborhood can turn on itself out of fear. It’s more relevant today than it was in 1960.

The Sitcom Trap

Then you have the sitcoms. People laugh at I Love Lucy because of the slapstick, but Lucille Ball was a technical genius. She basically invented the three-camera setup that is still used for live-audience shows today. Before her, you couldn't really do high-quality syndication because the film quality was garbage. She insisted on shooting on high-grade 35mm film, which is why Lucy still looks crisp on a 4K TV while shows from the 90s look like they were filmed through a sourdough starter.

👉 See also: Cuba Gooding Jr OJ: Why the Performance Everyone Hated Was Actually Genius

Actors Who Actually Had "The Look"

There’s a specific kind of magnetism that’s missing from a lot of today’s stars. Part of it was the studio system, which was admittedly predatory and weird, but it also knew how to manufacture icons. When Humphrey Bogart walked onto a screen, he didn't just play a character; he brought a whole atmosphere with him. It was a mix of world-weariness and hidden integrity.

Think about Bette Davis or Joan Crawford. They weren't just "actresses." They were forces of nature. They had faces that could tell a whole story without a single line of dialogue. Today, we have "relatable" actors. Back then, they were gods and goddesses. They were larger than life. Is that better? Maybe not for their mental health, but for the screen, it was electric.

There’s also the matter of the "Transatlantic Accent." That weird, mid-Atlantic way of speaking that sounded like a mix of London and New York. Nobody actually spoke like that in real life, but it gave classic movies and tv a sense of timelessness. It elevated the dialogue. It made every conversation feel like a duel.

The Practical Effects Peak

We are currently living in a CGI wasteland. Everything is a gray blob of pixels. In the 70s and 80s, if you wanted a giant shark or a terrifying alien, you had to build the damn thing.

- Jaws: The shark (Bruce) famously didn't work. Spielberg had to hide it for most of the movie, which ended up making it scarier.

- The Thing: Rob Bottin’s practical effects are still more disgusting and visceral than anything a computer can churn out.

- Star Wars: Those models and matte paintings have a tactile reality that the prequels and sequels often struggle to replicate.

When an actor is looking at a real, physical object, their performance changes. Their pupils dilate. Their sweat is real. You can feel the physics of the world. In Mad Max: Fury Road (which is a modern classic, let’s be real), the stunts feel dangerous because they were actually happening. Classic cinema was built on that danger.

✨ Don't miss: Greatest Rock and Roll Singers of All Time: Why the Legends Still Own the Mic

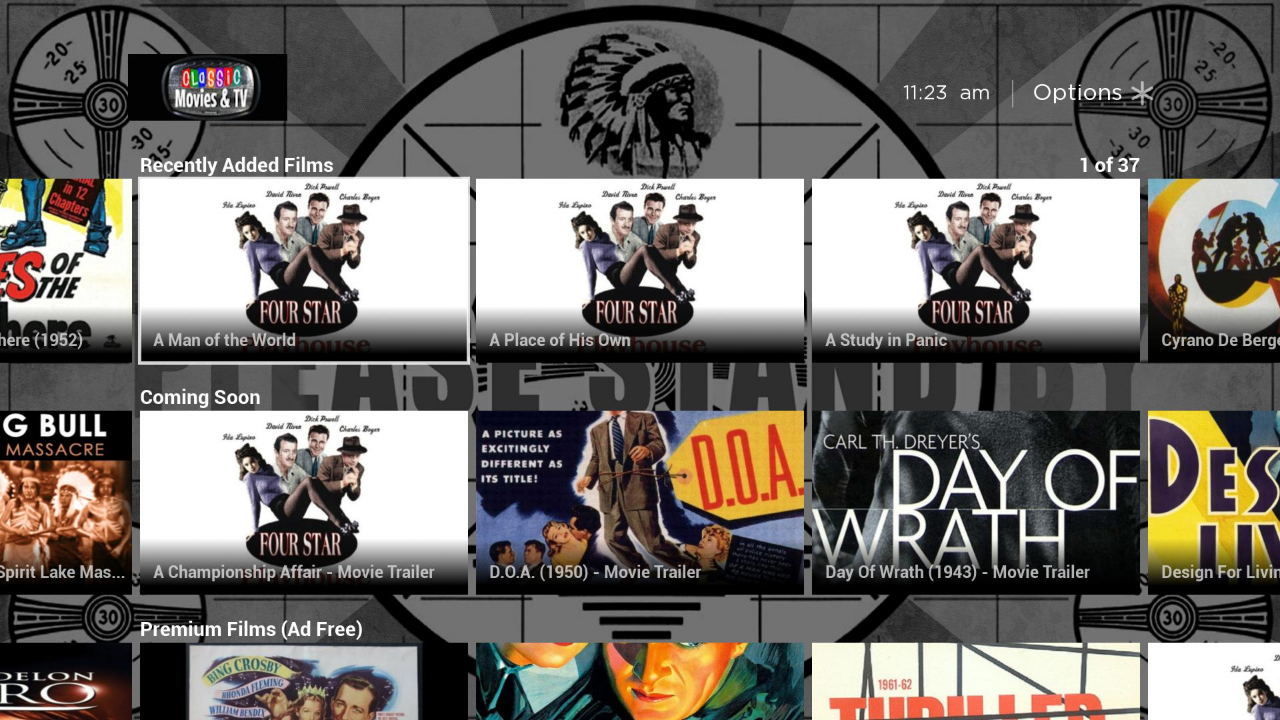

How to Actually Get Into the Old Stuff

If you want to dive into classic movies and tv, don't just start with the "Top 10" lists on IMDb. Those can be a bit dry. You have to find your gateway drug.

If you like psychological thrillers, skip the modern stuff and watch Gaslight (1944) or Night of the Hunter. If you want a comedy that actually makes you laugh out loud, watch Some Like It Hot. The ending is arguably the best punchline in cinematic history. For TV, don’t start with Leave it to Beaver unless you want a toothache from the sweetness. Go for The Dick Van Dyke Show. The chemistry between Van Dyke and Mary Tyler Moore is more modern and sharper than most 2000s sitcoms.

The Essential Watchlist (The "Non-Boring" Edition)

- Seven Samurai (1954): It’s long, but it’s basically every action movie ever made. If you’ve seen The Magnificent Seven or A Bug’s Life, you’ve already seen this story. Watch the original. The battle in the rain is legendary.

- Sunset Boulevard (1950): A dark, cynical look at Hollywood that feels incredibly bitter even by today’s standards. The opening shot is a dead guy talking to you from a swimming pool.

- The Prisoner (1967): If you like Black Mirror or Lost, this is the grandfather of the "weird island mystery" genre. It’s surreal, paranoid, and totally bizarre.

- Columbo: Peter Falk’s performance is a masterclass. Unlike modern procedurals where it’s a "whodunnit," Columbo is a "howcatchem." You see the murder happen in the first ten minutes. The joy is watching the smartest guy in the room pretend to be the dumbest guy in the room.

The Preservation Crisis

We are losing our history. A staggering percentage of silent films are gone forever—lost to nitrate fires or simply tossed in the trash because studios didn't think they had value. Even with classic movies and tv from the 50s and 60s, we are at the mercy of streaming services that "rotate" titles.

Physical media is the only way to ensure these things stick around. If you love a movie, buy the Blu-ray. The Criterion Collection and companies like Kino Lorber do incredible work restoring these films so they look better than they did when they premiered. Supporting these labels is the only way to keep the history of the medium alive.

The Action Plan for New Viewers

Stop treating classic cinema like homework. It’s not a chore; it’s a goldmine. If you’re tired of the "Marvel formula" or the "Netflix look," go back to the source.

- Pick a Director: Find someone whose style you like. If you like suspense, go Hitchcock. If you like fast-talking comedy, go Billy Wilder. If you like visual grandeur, go David Lean.

- Ignore the Year: Stop looking at the release date. A good story is a good story, whether it was filmed in 1939 or 2024.

- Check the Supplements: If you buy a physical copy, watch the "making of" features. Learning about the technical hurdles they had to overcome makes the final product even more impressive.

- Turn Off the Lights: These movies were designed for a dark room. Give them your full attention. No phone. No second screen.

The reality is that classic movies and tv offer a sense of intentionality that is rare in the modern world. Every frame was a choice. Every line of dialogue had to count. Once you start seeing the strings, you can’t go back to the "content" treadmill. You’ll find yourself looking for that old-school magic every time you pick up the remote.