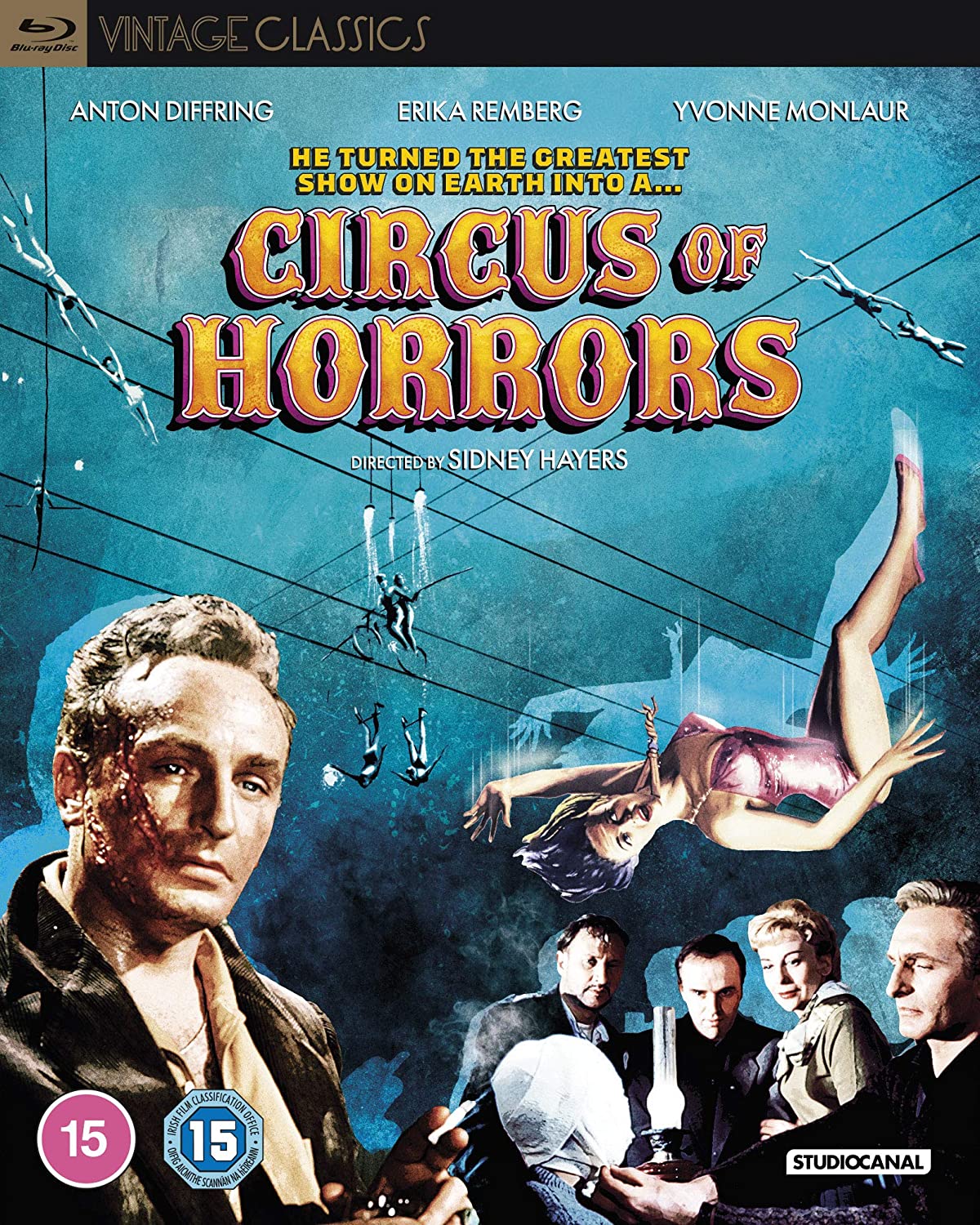

You’ve probably seen the poster. A woman screaming, garish colors, and the promise of "The Temple of Female Beauty" turned into a slaughterhouse. It looks like typical 1960s drive-in fodder, doesn't it? But Circus of Horrors 1960 is actually a much stranger, meaner beast than the marketing suggested. It’s part of what critics eventually dubbed the "Sadian Trilogy," a trio of films—including Peeping Tom and Horrors of the Black Museum—that pushed British censorship to its absolute breaking point.

Honestly, it’s a miracle it got made. In an era where Hammer Film Productions was busy reviving Dracula and Frankenstein with a certain gothic elegance, Circus of Horrors went the opposite way. It was lurid. It was sweaty. It felt dangerously contemporary.

The Plot That Most People Get Wrong

People often remember this as a generic slasher. It isn’t. The story follows Dr. Rossiter, played with a chilling, arrogant intensity by Anton Diffring. Rossiter is a brilliant plastic surgeon, but there’s a catch: he’s a fugitive. After a botched operation leaves a socialite's face looking like a road map, he flees to France. He changes his name to Dr. Schüler and acquires a run-down circus.

Why a circus? Because it’s the perfect cover for his "Temple of Beauty."

He finds women who have been scarred or disfigured by life—criminals, outcasts, prostitutes—and rebuilds their faces with his experimental surgery. He turns them into the stars of his show. But here is where the "horrors" part of Circus of Horrors 1960 kicks in. If any of these women try to leave his "ownership" or threaten to expose his past, they meet with a fatal "accident" during their performance.

One falls from a trapeze. Another is mauled by a lion. One is impaled by a knife-thrower.

The film isn't just about gore; it’s about a man’s pathological need to control female beauty through the scalpel. It’s surgical horror before that was even a recognized subgenre.

Why the "Sadian Trilogy" Label Actually Matters

The term wasn't coined by the filmmakers. It was the legendary critic David Pirie who grouped Circus of Horrors with Peeping Tom and Horrors of the Black Museum. Why? Because all three films share a specific, uncomfortable obsession with voyeurism and the infliction of pain.

🔗 Read more: Anjelica Huston in The Addams Family: What You Didn't Know About Morticia

In Circus of Horrors, the audience is forced into a double role. We are watching a movie, but we are also watching the circus audience within the movie. We are effectively paying to watch these women be "displayed" and then "destroyed." It’s incredibly cynical. If you compare it to Peeping Tom (released the same year), you see the same DNA. While Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom was reviled and effectively ended his career, Circus of Horrors was a massive box office hit.

Why did it succeed where Powell’s masterpiece failed?

Mostly because it hid its darkness behind the colorful, kitschy trappings of the Big Top. It felt like a "B-movie," so the critics didn't take it as a personal insult to British morality—at first. But look closer. The film uses Eastmancolor to make the blood look like bright red paint, creating a visual style that would later influence Italian giallo directors like Mario Bava and Dario Argento.

The Real Stars: Diffring and the "Circus of Beauties"

Anton Diffring was a German actor who spent most of his career being typecast as the "cold Nazi officer." In Circus of Horrors, he takes that icy, Teutonic precision and applies it to a mad scientist. He doesn't play Schüler as a cackling villain. He plays him as a man who genuinely believes he is a god.

Then you have the women. Erika Remberg, Yvonne Monlaur, and Vanda Hudson.

They weren't just scream queens. Their characters were often more sympathetic than the "heroes." You feel the tragedy of their situation. They are trapped in a cycle of gratitude and terror. They owe their beauty to a monster. When Hudson’s character, Magda, meets her end during the knife-throwing act, it’s genuinely harrowing because the film takes the time to show her desperation.

The movie also features a surprisingly catchy pop song, "Look for a Star," sung by Garry Mills. It reached the Top 10 in both the UK and the US. It’s this weird, sugary ballad that plays over scenes of impending doom. It’s jarring. It’s unsettling. It’s exactly what makes this film stand out sixty years later.

💡 You might also like: Isaiah Washington Movies and Shows: Why the Star Still Matters

Behind the Scenes: The Anglo-Amalgamated Factor

Anglo-Amalgamated was the studio behind this, and they were the kings of low-budget, high-impact cinema. They knew exactly what the public wanted: sex and violence, thinly veiled by a plot about "medical ethics."

Producer Julian Wintle and director Sidney Hayers didn't set out to make art. They set out to make money. But because they were working within the constraints of the 1960 British Board of Film Censors (BBFC), they had to be clever. They used shadows, quick cuts, and the implication of surgery.

The BBFC was notoriously strict. They hated "gratuitous" shots of blood. Yet, Circus of Horrors managed to slip through some of the most gruesome sequences of its time. The scene where Rossiter performs surgery in a barn, lit by lanterns, is pure atmosphere. It’s gritty. It feels illegal.

Technical Details for the Film Nerds

If you’re watching this today, you’ve got to appreciate the cinematography by Douglas Slocombe. Yes, that Douglas Slocombe—the man who went on to shoot Raiders of the Lost Ark.

His work here is phenomenal. He uses deep blacks and saturated primaries to give the circus a dreamlike, yet claustrophobic feel. Even when the camera is in the middle of a wide-open circus ring, you feel trapped.

Release Context:

- Release Date: May 1960 (UK)

- Director: Sidney Hayers

- Writer: George Baxt

- Runtime: 92 minutes

- Budget: Estimated at around £100,000 (very low, even for the time)

The film was shot largely at Billy Smart’s Circus, which added a level of authenticity. The performers you see in the background aren't extras; they are real circus folk. That’s why the atmosphere feels so thick. You can almost smell the sawdust and the animal musk.

📖 Related: Temuera Morrison as Boba Fett: Why Fans Are Still Divided Over the Daimyo of Tatooine

Common Misconceptions About the Film

One big myth is that it’s a Hammer film. It’s not. While it shares the "Technicolor Gothic" look, its soul is much more modern. Hammer was safe; Circus of Horrors feels like it wants to hurt you.

Another misconception is that it’s just a "bad movie" or camp. While some of the acting is a bit heightened, the central theme of a man using plastic surgery to "fix" and then control women is remarkably ahead of its time. It’s a proto-feminist nightmare. It predates the "body horror" movement popularized by David Cronenberg by decades.

Actionable Insights for Cult Cinema Fans

If you're planning to dive into the world of 1960s British horror, you can't just stop at Circus of Horrors. To truly understand the "Sadian" movement and how this film shaped the genre, follow these steps:

1. Watch the Trilogy in Order

Start with Horrors of the Black Museum (1959), move to Circus of Horrors (1960), and finish with Peeping Tom (1960). You will see a clear escalation in how the directors challenge the audience’s morality.

2. Seek Out the Uncut Version

Many TV edits of Circus of Horrors trim the surgery scenes or the more intense "accidents." Look for the Blu-ray releases from boutiques like Network or Kino Lorber. The restored color makes a huge difference.

3. Compare with "The Skin I Live In"

If you want a modern perspective, watch Pedro Almodóvar’s The Skin I Live In. The parallels between Antonio Banderas’ character and Anton Diffring’s Dr. Rossiter are striking. Both involve a surgeon obsessed with recreating a specific vision of a woman.

4. Listen to the Soundtrack

Pay attention to how the "Look for a Star" motif is used. It’s a masterclass in using "mickey-mousing" (matching music to action) ironically.

The film ends not with a hero’s triumph, but with a chaotic, bloody mess in the circus ring. It doesn't offer easy answers. It doesn't tell you that the world is a safe place. It tells you that beauty is a cage and that the people who claim to "fix" us are often the ones we should fear the most.

Final Takeaway: Circus of Horrors 1960 remains a vital piece of cinema history because it refused to be "polite" British horror. It’s messy, mean-spirited, and visually stunning. Whether you’re a fan of slasher history or 1960s aesthetics, this film is a mandatory watch. Get the 4K restoration, turn off the lights, and pay attention to the way it handles the gaze of the audience. It's looking right back at you.