Light is weird. If you get small enough, it stops being a beam and starts acting like a hail of tiny bullets. Capturing just one of those "bullets"—a single photon—is basically the holy grail of modern sensing. That is where the circuit single photon avalanche photodiode (SPAD) comes in. Honestly, calling it a "sensor" feels like an understatement. It is more like a microscopic lightning strike waiting to happen.

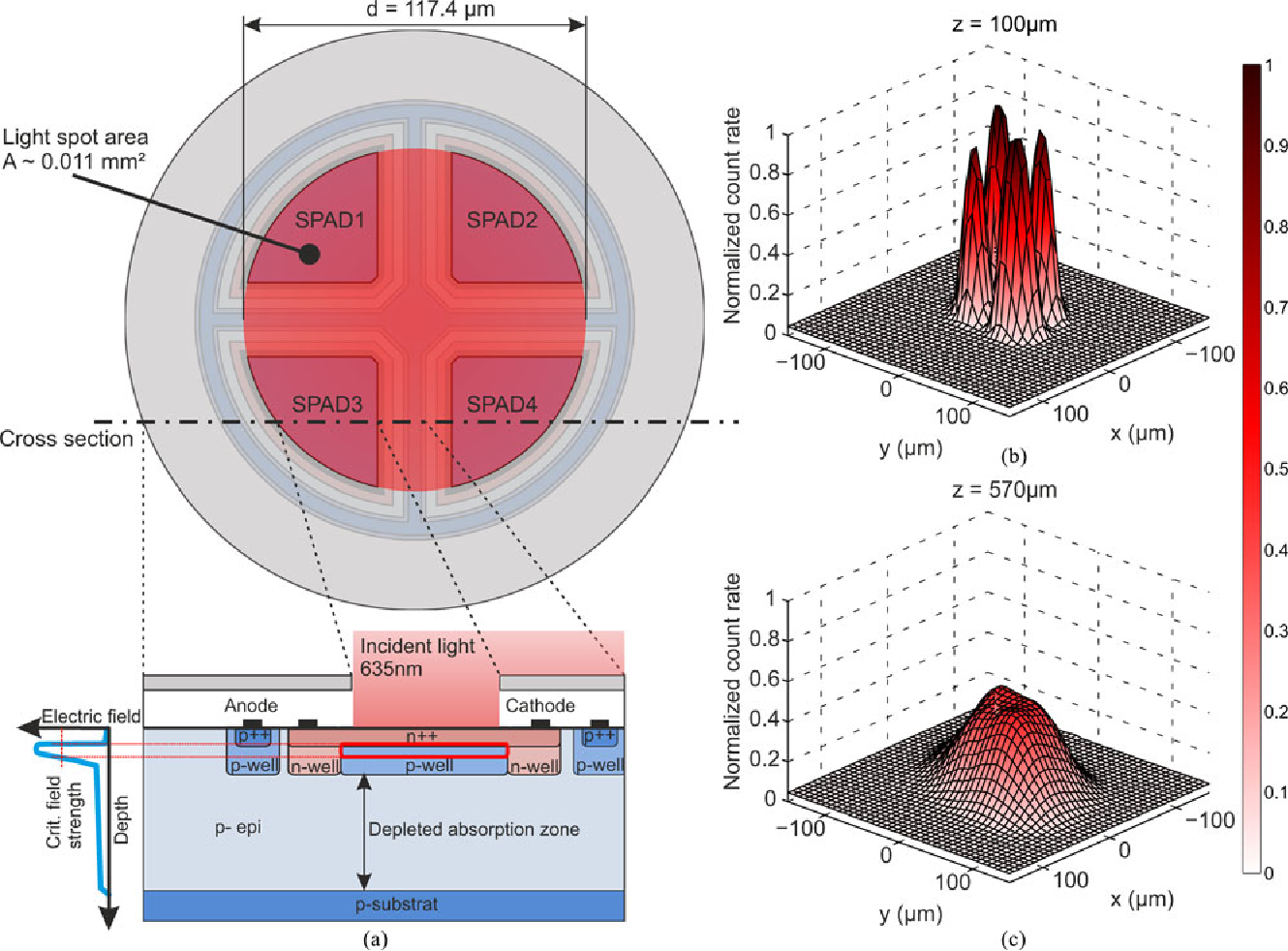

When a single photon hits the semiconductor material of a SPAD, it creates a carrier. Because the circuit is biased way above its breakdown voltage—a state we call "Geiger mode"—that one carrier triggers a massive internal landslide of electrons. Boom. You have a measurable pulse.

How the SPAD Actually Functions Under Pressure

It is all about the electric field. In a standard photodiode, you get one electron for every photon if you're lucky. In a SPAD, the internal field is so intense that an incoming electron gains enough kinetic energy to knock other electrons loose from the crystal lattice. This is impact ionization.

But here is the catch: once that avalanche starts, it doesn't just stop on its own. The circuit stays "on" and saturated. If you don't shut it down, the device will literally cook itself or just stay uselessly high, unable to detect the next photon. This is where the "circuit" part of the circuit single photon avalanche photodiode becomes the most important part of the conversation. You need a quenching circuit to sense the pulse and then immediately drop the voltage to reset the device.

The Quenching Problem: Passive vs. Active

Most people think the diode does all the work. It doesn't. The quenching circuit is the unsung hero.

Passive quenching is the simple way. You put a high-value resistor in series with the SPAD. When the avalanche hits, the current draws a huge voltage across that resistor, which naturally drops the voltage across the diode. It's cheap. It's easy. But it is also slow. The "dead time"—the period where the sensor is blind while it resets—is long.

Active quenching is where the real magic (and the real engineering headaches) happens. You use a fast comparator to sense the avalanche and then use a logic gate to actively "pull" the bias voltage down. Then, after a precise delay, you "push" it back up. This lets you reach count rates that would make a passive circuit choke. If you're building a LiDAR system for a self-driving car, you can't afford a lazy sensor. You need that active reset.

Real-World Messiness and Dark Counts

If you talk to anyone at Hamamatsu or Excelitas, they’ll tell you the same thing: thermal noise is the enemy.

Sometimes, an electron gets shook loose by heat instead of a photon. The SPAD can't tell the difference. It fires anyway. This is what we call the Dark Count Rate (DCR). If your DCR is too high, your signal is buried in garbage. This is why high-end circuit single photon avalanche photodiode setups often involve thermoelectric cooling. Even a few degrees can be the difference between a clean signal and a wall of static.

Then there’s "afterpulsing." During an avalanche, some charge carriers get trapped in defects in the semiconductor. Later, they release and start a second, fake avalanche. It’s like an echo that ruins your data. To fix it, you have to increase the dead time, which feels counterintuitive but is often the only way to ensure the traps are empty before you turn the lights back on.

Where These Things are Actually Used Right Now

We aren't just talking about lab experiments anymore.

- Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging (FLIM): In biology, we stain cells with dyes that glow. But it's not just about if they glow, it's about how long they take to stop glowing. We're talking nanoseconds. A SPAD circuit is one of the few things fast enough to time that.

- Quantum Key Distribution (QKD): This is the future of unhackable internet. You’re literally sending information one photon at a time. If someone tries to "listen," they disturb the photon. You need a SPAD to receive that quantum "key."

- Automotive LiDAR: While many systems use standard APDs (Avalanche Photodiodes), the shift toward SPAD arrays is real. Why? Because SPADs provide digital-like pulses that are easier to integrate directly onto CMOS chips.

The CMOS Revolution

For a long time, SPADs were discrete components. They were bulky and expensive. But recently, researchers have figured out how to build the circuit single photon avalanche photodiode directly into standard CMOS (Complementary Metal-Oxide-Semiconductor) processes.

This changed the game.

Now, you can put the diode and the quenching electronics on the same piece of silicon. You can build arrays of thousands of SPADs. This is how we get the "Time of Flight" sensors in modern smartphones. That little sensor next to your phone camera that helps with depth-of-field? That’s a SPAD array. It’s measuring the time it takes for a laser pulse to bounce off your nose and back to the phone.

🔗 Read more: Why the Japanese Air Conditioned Jacket is Changing How We Survive Summer

Why You Should Care About Jitter

In the world of single photons, timing is everything. "Jitter" is the uncertainty in the time between the photon hitting the sensor and the electrical pulse coming out.

If you have a jitter of 100 picoseconds, that sounds fast. But light travels about 3 centimeters in that time. If you’re trying to do high-precision 3D mapping, 3 centimeters of error is a lot. Designers are constantly fighting to reduce the jitter in the quenching circuit to get that precision down to the millimeter range. It's a brutal game of chasing picoseconds.

Limitations and the "No Free Lunch" Rule

It isn't all perfect. SPADs have a relatively low Photon Detection Efficiency (PDE) compared to some other sensors. You might only catch 25% or 50% of the photons that hit the active area. The rest just pass through or get lost.

Also, they can be noisy. If you need to see a very dim, slow-moving object, a cooled CCD might actually be better. SPADs are for when you need speed and individual particle counting.

Actionable Insights for Implementation

If you are looking to integrate a SPAD circuit into a project or product, keep these three things in mind:

- Match your wavelength: SPADs made of Silicon are great for visible light and near-infrared (up to about 900nm). If you're working in the 1550nm range (telecom fiber), you'll need InGaAs/InP materials, which are much more temperamental and expensive.

- Prioritize the Quenching Circuit: Don't just buy a diode and slap a resistor on it unless you don't care about speed. Look for integrated CMOS SPADs if you need a compact design with fast reset times.

- Thermal Management is Non-Negotiable: Even if you aren't using liquid nitrogen, a stable temperature environment will save you hours of calibrating out dark count drifts.

The circuit single photon avalanche photodiode is effectively the bridge between the macroscopic world we live in and the quantum world of individual light particles. Whether it is helping a car see in the dark or enabling a secure quantum phone call, the circuit design determines whether we get a clear picture or just a mess of electronic noise.