Christian Dior didn't just design clothes. He basically engineered a decade. When you think about the silhouette of the mid-century—that sharp, nipped-in waist and the skirt that looks like an opening flower—you’re thinking about Christian Dior in the 1950s. It was a decade of total dominance. Honestly, it’s hard to overstate how much one man in a grey flannel suit controlled the global aesthetic from a townhouse on Avenue Montaigne.

Post-war Paris was a mess. Rations were still a thing. Fabric was scarce. Then Dior shows up in 1947 with the "New Look" (which was actually called the Corolle line) and just flips the table. By the time 1950 rolled around, he wasn't just a designer anymore. He was an export powerhouse. Roughly half of all French fashion exports were Dior products. Think about that for a second. One guy was responsible for 50% of a major national industry’s prestige output.

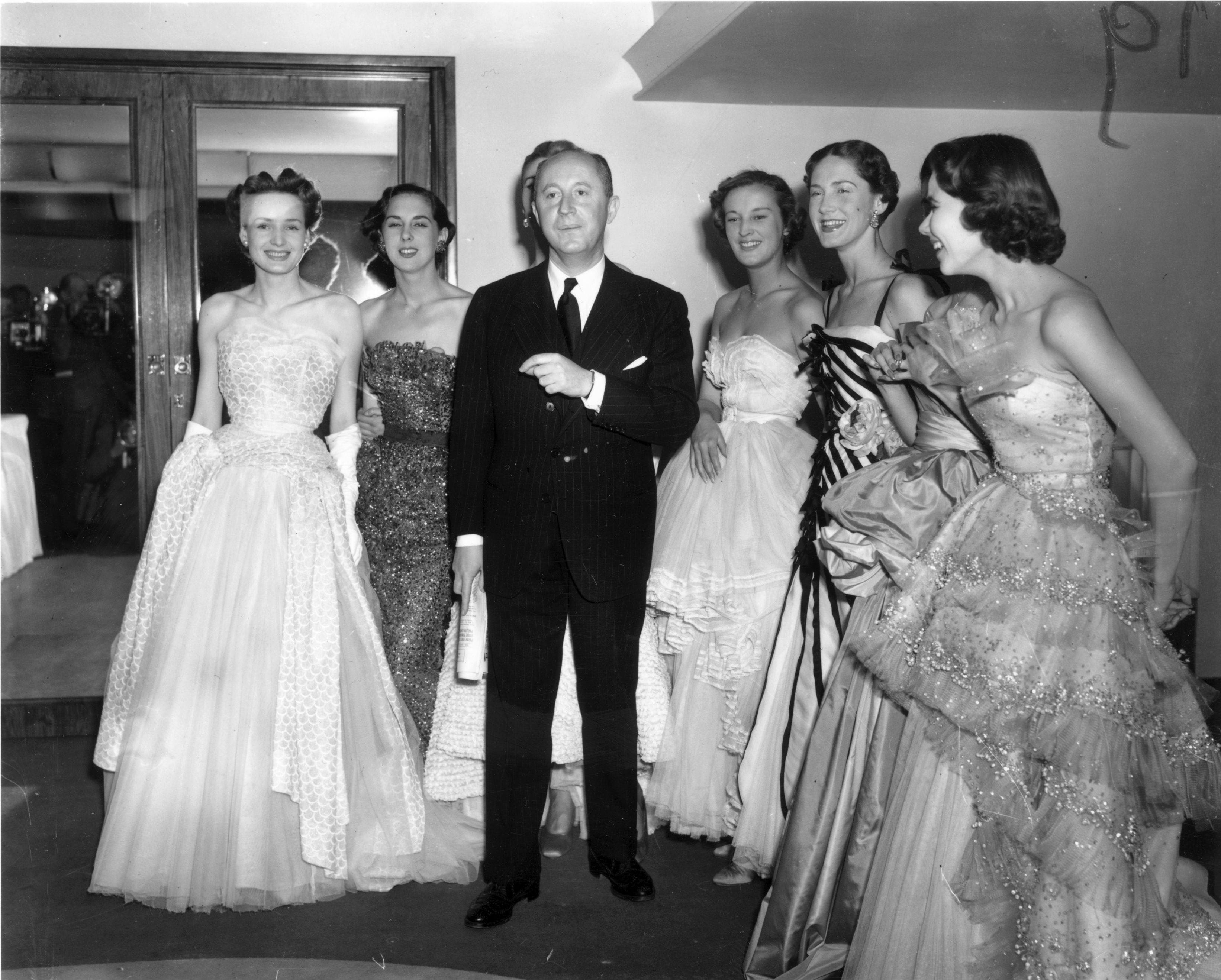

The Architecture of the 1950s Silhouette

Dior was obsessed with structure. He didn't just drape fabric; he built scaffolding. He used to say he wanted to be an architect, and you can see it in the way he treated the female body like a blueprint.

The early 1950s were defined by the Vertical Line (1950) and the Oblique Line (1951). These weren't just catchy names. They were radical shifts in geometry. While the 1940s were all about boxy shoulders and short, practical skirts necessitated by the war, Dior went the opposite way. He wanted excess. He used yards and yards of tulle, percale, and silk taffeta. Some of those evening gowns weighed several pounds because of the internal corsetry and boning hidden under the surface. It was restrictive, yeah. It was also undeniably glamorous.

The H, A, and Y Lines

By 1954, things got weird—in a good way. Dior introduced the H-Line. If you’ve ever seen a "pencil" look that deemphasizes the bust and creates a straight, elongated torso, that’s the H-Line. It was a huge departure from the hourglass. Then came the A-Line in 1955. We use that term constantly now, but back then, it was a specific geometric vision: narrow shoulders widening out toward the hem. A year later, the Y-Line hit, featuring huge collars or wide stoles that tapered down to a slim skirt.

🔗 Read more: Finding the Right Word That Starts With AJ for Games and Everyday Writing

He changed the "shape" of the world every six months. People waited for his shows like they wait for iPhone launches now.

A Business Empire Built on Licences

Dior was a bit of a genius when it came to money. He realized early on that not everyone could afford a bespoke haute couture gown that cost as much as a small car. So, he pioneered the licensing model.

He put his name on stockings. He put it on ties, perfumes, and gloves. Most people don't realize that the "Diorama" and "Miss Dior" scents weren't just side projects; they were the financial engine that kept the couture house running. In 1953, he hired Roger Vivier to design shoes, which basically invented the concept of the luxury designer footwear collaboration. It was the first time a couture house really branched out into a "lifestyle brand" before that term even existed.

He faced a lot of heat for it. The "purists" in the French fashion guild thought he was cheapening the craft by selling stockings in department stores. He didn't care. He knew that the 1950s were the beginning of the consumer age. You've gotta follow the market.

💡 You might also like: Is there actually a legal age to stay home alone? What parents need to know

The Celebrities and the Mystique

If you were a "somebody" in the 1950s, you were wearing Dior. Period. Princess Margaret wore a massive Dior gown for her 21st birthday in 1951—it's one of the most famous dresses in British royal history. Marlene Dietrich famously refused to film Stage Fright unless she could wear Dior, telling Alfred Hitchcock, "No Dior, no Dietrich."

- Ava Gardner had a whole wardrobe of Dior for her public appearances.

- Rita Hayworth was a regular at the salons.

- The Duchess of Windsor (Wallis Simpson) was perhaps his most loyal—and demanding—client.

The atmosphere at 30 Avenue Montaigne was intense. It wasn't just a shop. It was a temple. Dior was famously superstitious, always consulting a clairvoyant, Madame Delahaye, before making major business moves or naming a collection. He’d look for lucky charms like a piece of iron or a four-leaf clover. This weird mix of high-end business savvy and mystical superstition is what gave the brand its soul.

Why it Ended So Abruptly

Dior’s reign in the 50s was short but absolute. He died of a heart attack in 1957 while on vacation in Italy. He was only 52. The fashion world went into a total tailspin. Who replaces a god?

The answer was a 21-year-old kid named Yves Saint Laurent.

📖 Related: The Long Haired Russian Cat Explained: Why the Siberian is Basically a Living Legend

Saint Laurent had been Dior's assistant, and his first collection in 1958—the "Trapeze" line—saved the company from bankruptcy. It carried the Dior spirit but moved it toward the more relaxed 1960s. But the 1950s? Those belonged strictly to Christian. He took the world from the drabness of the war and painted it in "Rouge Dior" lipstick and midnight blue silk.

What You Can Learn from Dior's 1950s Legacy

If you're into fashion, or just interested in how brands are built, the Dior era is the ultimate case study. It wasn't just about "pretty dresses." It was about understanding the psychology of the era. People were tired of being "sensible." They wanted to be "extra."

Practical Takeaways:

- Invest in Tailoring: Dior proved that the fit of a garment (the internal structure) is more important than the fabric on top. A cheap dress tailored perfectly looks better than a designer bag on a messy outfit.

- The "Power of the Accessory": He proved you can build a multi-billion dollar empire on the "small stuff" like perfume and shoes. If you're building a personal brand, don't ignore the details.

- Consistency is Key: Throughout the 50s, Dior never deviated from his high standards of "Le Grand Luxe," even when the world started moving toward ready-to-wear. He knew his niche and he stayed in it.

To really see this in action, check out the Musée des Arts Décoratifs archives or the various "Christian Dior: Designer of Dreams" exhibitions that tour globally. Seeing these 1950s pieces in person is wild—the stitching is so fine it almost looks invisible. It reminds you that before the 1950s were a "vibe" on Pinterest, they were a meticulously crafted reality.