He was twenty. Think about that for a second. Frederic Chopin was barely out of his teens when he premiered the Chopin Piano Concerto No 1 in E minor, Op. 11. Most twenty-year-olds today are figuring out how to use a washing machine or debating what to post on TikTok. Chopin, meanwhile, was standing on a stage in Warsaw in October 1830, performing a work that would basically change how people thought about the piano forever. It was his final "goodbye" to Poland. Within weeks, the November Uprising broke out. He never went back.

Honestly, there’s a massive misconception that this concerto is just "pretty" background music. People hear the shimmering piano lines and think it’s just high-society wallpaper. They’re wrong. This piece is a technical nightmare for the performer and a deeply emotional, almost cinematic experience for the listener. If you’ve ever felt like an outsider or struggled to say goodbye to a place you love, you’re hearing Chopin’s literal diary in this music.

The Weird History of the "First" Concerto

Here is a bit of trivia that music students love to nerd out over: the Chopin Piano Concerto No 1 isn't actually his first.

Confused? You should be.

He actually wrote his "Second" Concerto (in F minor) before this one. But because the E minor concerto was published first, it got the "No. 1" tag. It’s like a movie sequel being released as the original. By the time he sat down to write the Op. 11, he was more confident. He was experimenting. He was also deeply, painfully in love with a soprano named Konstancja Gładkowska. He never really told her how he felt, at least not in plain Polish. Instead, he poured that adolescent longing into the second movement.

It’s romantic in the capital "R" sense. Not the Hallmark card kind of romance, but the kind that hurts.

Breaking Down the Movements

The first movement, the Allegro maestoso, starts with a massive orchestral introduction. Now, critics—especially the stuffy ones from the 20th century—loved to bash Chopin for his orchestration. They said he didn't know how to write for a full band. They claimed the orchestra was just a boring pedestal for the piano.

They kind of missed the point.

🔗 Read more: The Name of This Band Is Talking Heads: Why This Live Album Still Beats the Studio Records

Chopin was a brilliant minimalist when it came to the orchestra. He didn't want the violins screaming over the soloist. He wanted a cushion. When the piano finally enters, it doesn't just play; it commands. It hits you with these bold, fortissimo chords that say, "I’m here, and you’re going to listen."

Then we get to the Romanze – Larghetto. This is the heart of the Chopin Piano Concerto No 1. Chopin wrote to his friend Tytus Woyciechowskii about this movement, describing it as a "meditation in beautiful spring weather, but by moonlight." It’s meant to be a daydream. You can hear the influence of bel canto opera—the long, singing lines that sound like a human voice rather than a percussive instrument. If you aren't a little bit moved by the way the piano floats over the muted strings here, you might be a robot.

Finally, the Rondo – Vivace. This is where Chopin shows off his Polish roots. It’s based on the krakowiak, a fast, syncopated folk dance from the Kraków region. It’s bubbly. It’s virtuosic. It’s the sound of a young man who knows he’s the best in the room.

Why Musicians Actually Fear This Piece

If you talk to professional pianists like Seong-Jin Cho or Martha Argerich—both of whom have legendary recordings of the Chopin Piano Concerto No 1—they’ll tell you it’s a trap.

It looks easy on the page compared to something like a Rachmaninoff concerto. There aren't massive, fist-smashing chords. But the difficulty is in the "pearl" technique. Chopin requires these rapid-fire, delicate scales that have to sound like a string of pearls falling on glass. If you're a millisecond off, or if your touch is too heavy, the whole thing falls apart.

There's nowhere to hide.

The Problem with Orchestration

Let's address the elephant in the room: the orchestra.

💡 You might also like: Wrong Address: Why This Nigerian Drama Is Still Sparking Conversations

For decades, conductors tried to "fix" Chopin’s orchestration. Famous musicians like Karl Tausig and even the great Mikhail Pletnev have written re-orchestrated versions of the Chopin Piano Concerto No 1. They added more brass, more woodwind counterpoint, more "meat" to the sound.

But lately, the trend has shifted back to the original. Why? Because when you play it on period instruments or with a smaller chamber-sized orchestra, you realize Chopin knew exactly what he was doing. The lightness of the orchestra allows the piano's nuances—those tiny little trills and ornaments—to breathe. It’s not a battle between the soloist and the group. It’s a conversation.

What to Listen For

If you’re sitting down to listen to the Chopin Piano Concerto No 1 for the first time, don't just put it on as white noise while you answer emails. Try this:

- The First Entry: Notice how the piano waits. The orchestra plays for almost four minutes. When the piano finally cuts in, it’s dramatic. It’s like a lead actor walking onto a stage after a long buildup.

- The "Limp": In the third movement, listen for the rhythm of the krakowiak. It has this slight, rhythmic "hitch" or syncopation that gives it a rustic, folk-dance feel. It’s sophisticated, but it’s got dirt under its fingernails.

- The Bass Notes: Chopin was a master of using the lower end of the piano to create resonance. In the second movement, listen to how the left hand provides a deep, warm foundation for the right hand’s "singing."

The Legacy of Op. 11

The Chopin Piano Concerto No 1 essentially ended the "virtuoso for the sake of virtuosity" era. Before Chopin, concerto writers often just wrote a bunch of fast notes to show off. Chopin made those fast notes mean something. Every run, every arpeggio, every trill serves the emotional narrative.

He proved that you could be a "rockstar" pianist without sacrificing your soul.

When Chopin left Warsaw after the premiere, he carried a silver goblet filled with Polish soil. He kept it with him for the rest of his life in Paris. That same sense of displacement and longing is baked into the DNA of this concerto. It’s the sound of a home you can never go back to.

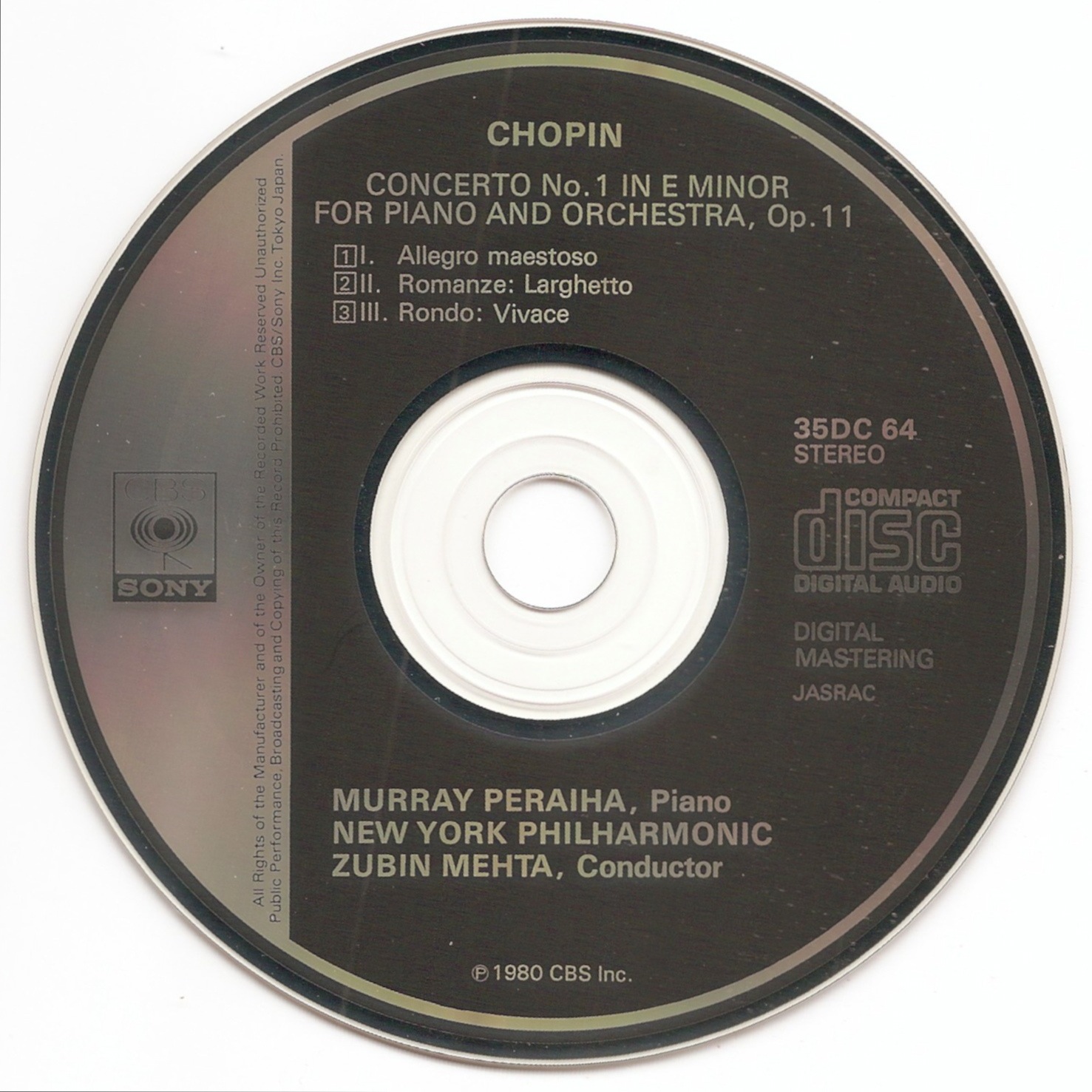

Choosing the Right Recording

You have options. If you want something fiery and fast, look for Martha Argerich’s 1968 recording with Abbado. She plays it like her life is on the line.

📖 Related: Who was the voice of Yoda? The real story behind the Jedi Master

If you want something more poetic and modern, Seong-Jin Cho’s performance from the 2015 International Chopin Piano Competition is basically the gold standard for the 21st century. He wins on the sheer clarity of his touch.

For a more "authentic" sound, check out a recording on a Pleyel piano from the 1830s. The sound is thinner, more metallic, and arguably much closer to what Chopin actually heard in his head.

Actionable Insights for Music Lovers

To truly appreciate the Chopin Piano Concerto No 1, you need to engage with it actively rather than passively.

- Compare the Movements: Listen to the second movement (the Larghetto) right after listening to a piece of Italian opera from the same era, like something by Bellini. You’ll immediately hear where Chopin got his "singing" style from.

- Watch the Hands: Go to YouTube and watch a high-quality "overhead" shot of a pianist playing the third movement. Notice the "quiet" hand position Chopin favored. There’s very little wasted movement. It’s a lesson in efficiency.

- Read the Letters: Find a copy of Chopin’s letters from 1830. Reading his own words about his "ideal" and his "unrequited love" while the second movement plays changes the experience entirely. It turns a piece of music into a historical document.

The Chopin Piano Concerto No 1 isn't just a relic of the Romantic era. It is a living, breathing testament to the power of the piano. It’s a bridge between the classical structures of Mozart and the wild, emotional landscapes of the late 19th century. Whether you're a seasoned musician or someone who just likes a good melody, there is always something new to find in these pages.

The next time you hear that opening E minor chord, don't just listen. Imagine a twenty-year-old kid in Warsaw, about to leave his world behind, putting everything he had into a few sheets of manuscript paper. That's where the magic is.

Explore the Technical Depth:

To get even closer to the music, try following along with a "miniature score." Even if you don't read music well, seeing the visual density of the piano part compared to the sparse orchestration tells the story of the work's balance better than any textbook ever could. Pay close attention to the sheer volume of notes in the piano's "cadenza-like" passages—it’s a visual representation of the composer’s restless energy during a time of political and personal upheaval.

Final Listening Tip: Try listening to the work in a completely dark room with headphones. This removes the "concert hall" artifice and lets the intimacy of the Romanze feel like it was written specifically for you. Chopin hated large crowds and preferred the intimacy of salons; this is the best way to honor his original intent.