If you’ve ever sat in a dimly lit room and felt a sudden, inexplicable ache in your chest while listening to a piano, there is a very high chance you were hearing the Chopin Nocturne Op 27 No 2. It is the D-flat major masterpiece. It’s the one that makes professional pianists sweat and amateur listeners weep. Honestly, it’s arguably the most perfect thing Frédéric Chopin ever wrote, and I don't say that lightly.

Most people recognize the Nocturne in E-flat Major, Op. 9, No. 2. You know the one—it's on every "Classical Music for Studying" playlist on YouTube. But the Op 27 No 2 is a different beast entirely. It’s more mature. It’s more complex. It’s basically the "grown-up" version of his earlier work. Composed in 1835 and published a year later, this piece marks the moment Chopin stopped just writing "pretty melodies" and started engineering emotional architecture.

The Anatomy of a Masterpiece

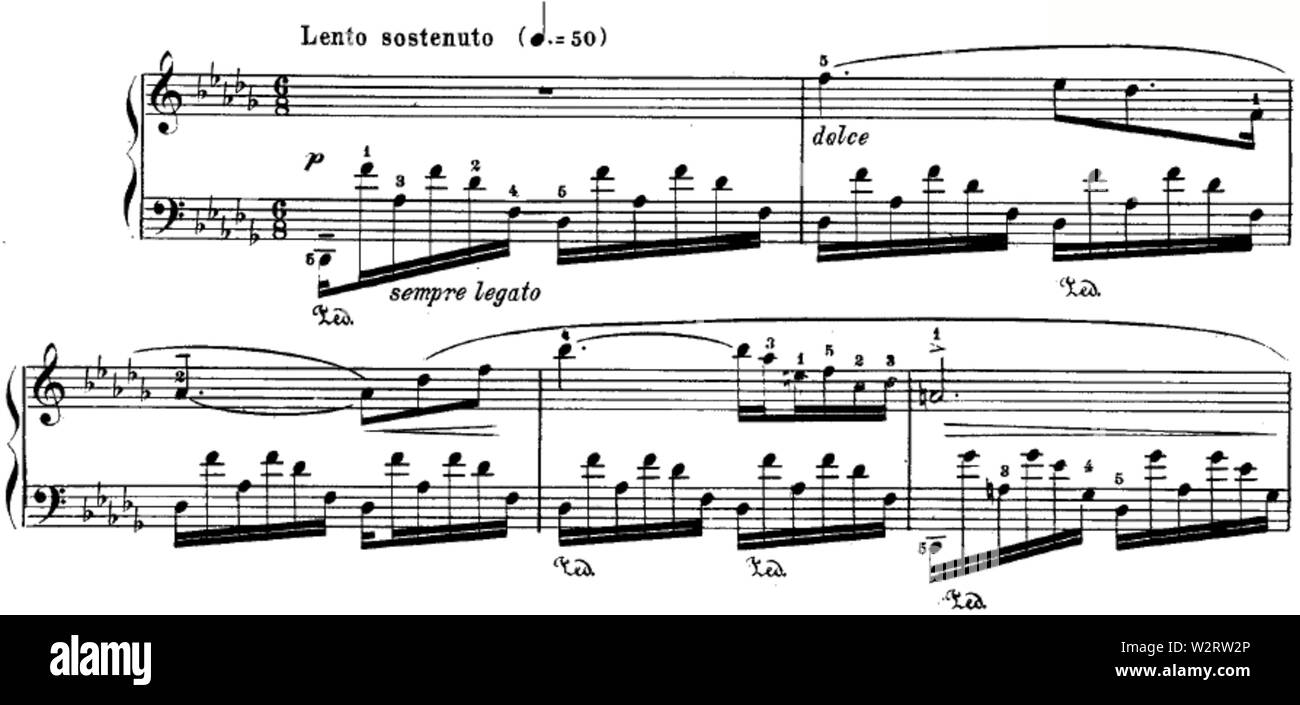

What's actually happening under the hood here?

Structurally, it’s a bit of a rebel. While a lot of nocturnes follow a standard A-B-A format (statement, contrast, return), this one is essentially a continuous variation. It grows. It breathes. It doesn't just repeat; it evolves. The left hand plays these wide, sweeping broken chords that span over two octaves. It’s a literal workout. If your hand isn't large enough or your wrist isn't supple, those intervals will kill you.

Then there's the right hand. This is where the magic—and the difficulty—lives. Chopin uses these "double notes" where the pianist has to play thirds and sixths with one hand while keeping the melody legato. It should sound like two people singing a duet, perfectly in sync. In reality, it’s one person trying to make a percussion instrument sound like a human voice.

Musicologists often point out that this piece is the pinnacle of bel canto style on the piano. Chopin was obsessed with Italian opera, specifically composers like Bellini. He wanted the piano to "sing" like a soprano. When you hear those long, winding melodic lines in Op 27 No 2, you aren't just hearing notes. You're hearing a vocal aria translated into hammers and strings.

Why It’s Not Just "Relaxing Piano Music"

People often pigeonhole nocturnes as "sleepy" music. That is a massive mistake here.

👉 See also: When Was Kai Cenat Born? What You Didn't Know About His Early Life

While the key is D-flat major—which is usually warm and comforting—Chopin laces the piece with dissonance. There are moments where the harmony grates against itself just for a second. It creates this sense of yearning or "zal," a Polish word Chopin used to describe a specific type of soulful regret.

It’s sophisticated.

The piece was dedicated to the Comtesse d'Apponyi. Now, the Countess wasn't just some random socialite; she was the wife of the Austrian ambassador in Paris. This piece was meant for the highest levels of the Parisian salons. It wasn't written for a concert hall with two thousand people. It was written for a small, intimate room filled with the smell of expensive perfume and the sound of rustling silk. You can feel that intimacy in the music. It feels like a secret being whispered directly into your ear.

Technical Hurdles Nobody Mentions

If you talk to a concert pianist about performing the Chopin Nocturne Op 27 No 2, they won't talk about the "pretty tune." They’ll talk about the fingering.

- The fiorituras. Those are the fast, decorative runs that look like a flock of birds on the page. They aren't supposed to be rhythmic. They should feel like they're floating.

- Tone control. Keeping the melody "above" the accompaniment is incredibly hard because the left hand is so busy.

- The ending. The coda is one of the most sublime moments in all of music. It’s a series of descending scales that eventually fade into nothingness. If you hit those last chords too hard, you ruin the entire ten-minute experience.

It’s about restraint.

Many students try to play this too early in their development. They can hit the notes, sure. But they can't make it breathe. There is a recording by Arthur Rubinstein that many consider the gold standard. He plays it with this incredible "rubato"—a stretching and squeezing of time. It doesn't sound like a metronome. It sounds like a heartbeat. If you want to understand this piece, go listen to Rubinstein or perhaps Maria João Pires. Their interpretations are worlds apart, but both capture that essential "something" that makes this nocturne immortal.

✨ Don't miss: Anjelica Huston in The Addams Family: What You Didn't Know About Morticia

The Misconception of "Sadness"

One of the biggest myths is that this nocturne is purely sad. Honestly? I don't buy it.

There's a strength in D-flat major. It’s a sturdy key. To me, the Op 27 No 2 is about resilience. It’s about finding beauty within the melancholy. It’s the sound of someone who has lost something but is still standing. When the melody climbs into the higher registers towards the end, it feels like a moment of clarity.

It’s also surprisingly modern. The way Chopin uses chromaticism—moving by half-steps—foreshadows composers like Wagner and even the Impressionists like Debussy. He was pushing the boundaries of what 19th-century ears were used to hearing. He wasn't just following the rules; he was rewriting them in real-time.

How to Actually Listen to It (And What to Look For)

If you're going to sit down and really engage with the Chopin Nocturne Op 27 No 2, don't just have it on in the background while you do the dishes. You'll miss the nuance.

Start by focusing on the bass line. That rolling 6/8 rhythm is the foundation. It never stops. It’s like the tide coming in and out. Once you have that pulse in your head, listen to how the melody interacts with it. Sometimes the melody is right on the beat. Other times, it’s dragging behind or pushing forward. That tension is where the emotion lives.

Look out for the "climax" about two-thirds of the way through. The music builds, the volume increases, and for a moment, the "nocturne" feel disappears and it becomes almost heroic. Then, just as quickly, it collapses back into that intimate whisper. It’s a masterclass in tension and release.

🔗 Read more: Isaiah Washington Movies and Shows: Why the Star Still Matters

Practical Steps for Enthusiasts and Players

Whether you're a listener or a student, there are ways to deepen your connection to this specific work.

For the Listeners:

Compare three different recordings. Seriously. Listen to Rubinstein (warmth), then Horowitz (drama), then Seong-Jin Cho (precision). You will realize they aren't even playing the same piece. The "score" is just a map; the performer provides the soul.

For the Pianists:

Don't rush into the tempo. The marking is Lento sostenuto. "Sostenuto" is the key word. Every note needs to be sustained and connected. Work on your left hand separately until you can play those arpeggios in your sleep. If your left hand is tense, your right hand will never be able to sing.

For the History Buffs:

Read Chopin’s letters from 1835. He was in a weird place—dealing with health issues and complicated social dynamics in Paris. Understanding his physical frailty makes the power of this music even more impressive. He was a small man with a massive internal world.

At the end of the day, the Chopin Nocturne Op 27 No 2 remains a staple of the repertoire because it refuses to be dated. It doesn't sound "old." It sounds human. It’s the sound of a person trying to make sense of the world using eighty-eight keys and a lot of imagination.

To truly appreciate this work, your next step is to find a high-quality FLAC or vinyl recording—avoiding the compressed audio of standard streaming if possible—and listen specifically for the "pedal points." Notice how Chopin uses the damper pedal to blur the colors together, creating a wash of sound that feels like a watercolor painting. Pay attention to the very last two chords; they should feel like a question being answered with a soft, confident "yes."