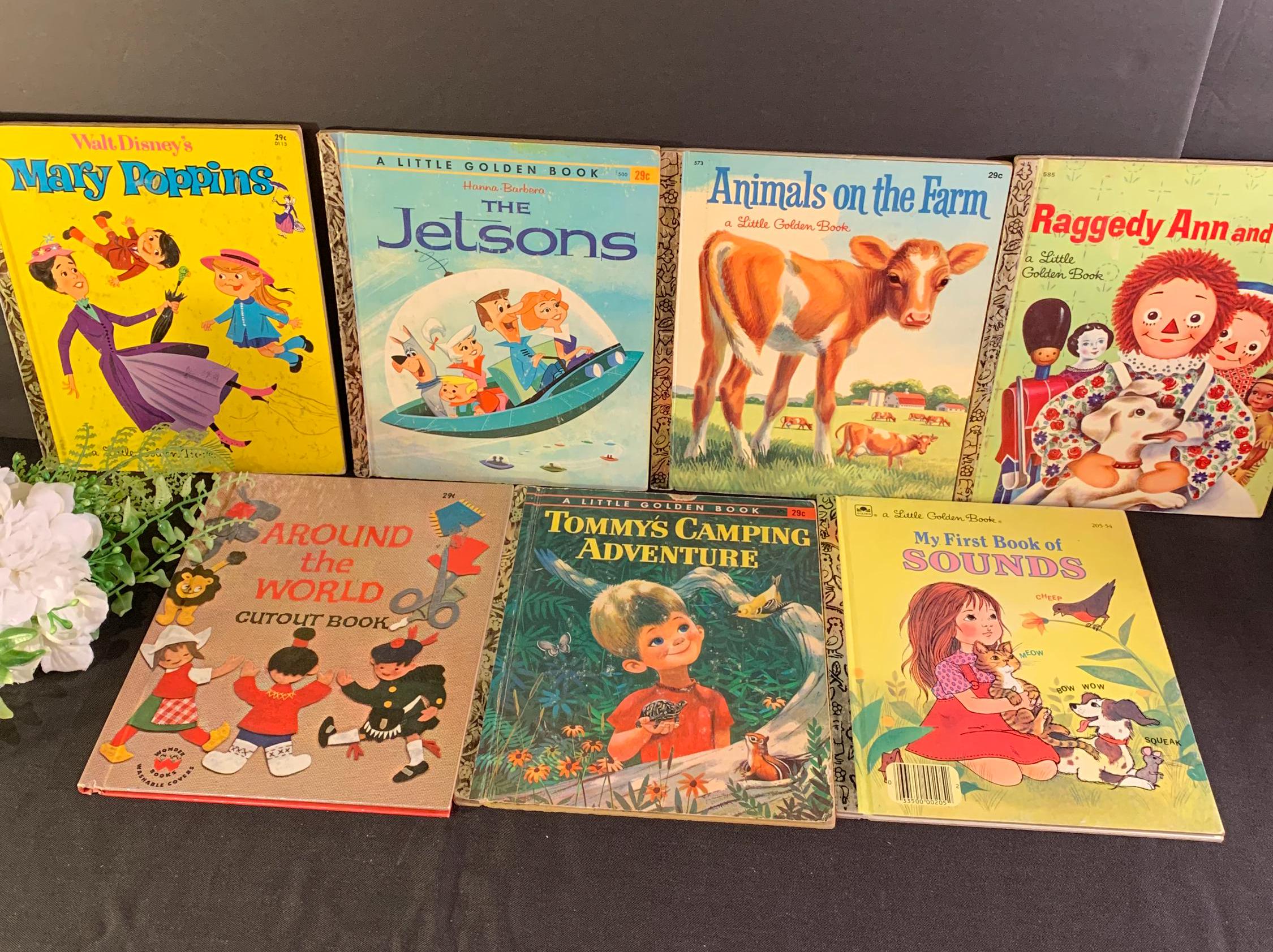

Walk into any used bookstore and you’ll smell it immediately. That vanilla-and-dust scent of old paper. If you’re a certain age, or if your parents were hoarders of nostalgia, your eyes will probably land on a spine that looks familiar. Maybe it’s the primary colors of a Harper & Row jacket or the iconic gold foil of a Little Golden Book. Children's books from the 1960s weren't just stories. They were a massive, colorful collision between the rigid post-war era and the psychedelic, rule-breaking chaos of the "Me Decade."

It was a strange time to be a kid. Honestly.

We’re talking about a decade where the Cat in the Hat had already cleared the way for "easy readers," but then things got experimental. Real fast. Writers and illustrators started realizing that kids weren't just small adults who needed to be lectured. They were people with anxieties, wild imaginations, and a growing awareness of a world that was—quite frankly—on fire. Between the Space Race and the Civil Rights Movement, the literature shifted. It got deeper. It got weirder.

The Maurice Sendak Revolution and the End of "Polite" Kids

If you want to understand why children's books from the 1960s changed everything, you have to talk about 1963. That was the year Where the Wild Things Are hit the shelves.

People hated it at first. Well, the adults did.

Librarians actually banned it in some places because they thought Max was too "frightening" or "defiant." Imagine that. A kid wearing a wolf suit and threatening to eat his mom was seen as a threat to the moral fabric of society. But Maurice Sendak knew something the critics didn't. He knew kids have big, scary emotions. He understood that a child’s anger is a physical, living thing. By the time Max sails back to his room where his supper is still hot, Sendak had effectively killed the "perfectly behaved child" trope that dominated the 1950s.

It wasn't just Sendak, though.

The mid-60s gave us Harriet the Spy (1964) by Louise Fitzhugh. Harriet wasn't a princess. She was a prickly, notebook-toting kid in a hoodie who lived in Manhattan and said things that were actually kind of mean. She spied on people. She had a therapist—or "Dr. Wagner"—which was almost unheard of in middle-grade fiction back then. Fitzhugh broke the mold by showing that a protagonist could be deeply flawed and still worth rooting for. It taught a whole generation that it was okay to be an outsider.

Why the Art Style Went Totally Off the Rails

Look at a book from 1952. Then look at The Very Hungry Caterpillar (1969).

📖 Related: Blue Bathroom Wall Tiles: What Most People Get Wrong About Color and Mood

The difference is staggering.

Eric Carle’s use of hand-painted tissue paper and collage was a technological and artistic pivot. Before this, illustrations were often tight, representational, and—let's be real—a bit stiff. The 1960s brought in the influence of pop art and Swiss design. Leo Lionni was doing incredible things with torn paper in Frederick (1967), telling a story about a mouse who was a poet instead of a worker. It was basically a hippie manifesto for toddlers. "I gather sun rays for the cold dark winter days," Frederick says. It was a soft, beautiful argument for the necessity of the arts.

And we can't forget Ezra Jack Keats.

When The Snowy Day won the Caldecott Medal in 1963, it was a massive deal. It featured Peter, a young Black boy in a bright red snowsuit, simply enjoying the weather. No "social message" slapped on the front. No tragic backstory. Just a kid and the snow. It sounds simple now, but in the context of 1962/1963, it was a revolutionary act of representation. Keats used collage and batik-like patterns that made the urban landscape look like a dreamscape.

The Weirdness of Roald Dahl and the Darker Side

If the 60s were about "flower power," Roald Dahl was the guy reminding everyone that nature—and people—can be pretty cruel.

James and the Giant Peach arrived in 1961. Charlie and the Chocolate Factory followed in 1964.

Dahl’s books are legendary for their "us vs. them" mentality. It was always the kids against the grotesque, abusive adults. Think about Aunt Spiker and Aunt Sponge. They weren't just "mean"; they were caricatures of greed and laziness. Children's books from the 1960s started leaning into this dark humor. Dahl’s work suggested that the world was a dangerous, nonsensical place, but if you were clever (and maybe had a giant insect or a magical chocolatier on your side), you might just survive.

There’s a specific kind of grit in these stories.

👉 See also: BJ's Restaurant & Brewhouse Superstition Springs Menu: What to Order Right Now

You see it in The Outsiders by S.E. Hinton, published in 1967. She wrote it when she was only sixteen. Sixteen! It wasn't a "picture book," but it redefined Young Adult fiction before "YA" was even a marketing term. It dealt with class warfare, gang violence, and death in a way that didn't talk down to teenagers. "Stay gold, Ponyboy." That line has more emotional weight than almost anything written for kids in the previous three decades combined.

The Science Fiction Surge and the Space Race

You can't talk about this era without mentioning A Wrinkle in Time (1962).

Madeleine L'Engle spent years trying to get this book published. Publishers thought it was "too difficult" for children. They thought the concepts of tesseracts and cosmic evil were too high-brow. They were wrong. Meg Murry became an icon for every girl who felt awkward, wore glasses, and was good at math.

The book blended quantum physics with a battle between light and darkness. It reflected the Cold War anxieties of the time—the fear of "The Black Thing" taking over the world and turning everyone into mindless, bouncing-ball-synchronized robots. It was a direct critique of the conformity of the 1950s.

Why These Books Still Rank on Our Bookshelves

So, why do we still care? Why are we still buying Swimmy or The Phantom Tollbooth for our nephews and grandkids?

Honestly, it's because these books don't treat childhood like a waiting room. They treat it like a frontier. The authors of this decade—Norton Juster, Shel Silverstein, Ursula K. Le Guin—were obsessed with the idea of agency. They wanted kids to think for themselves.

The Phantom Tollbooth (1961) is essentially a 250-page pun about the importance of education and critical thinking. Milo starts off bored with everything, and by the end, he realizes that "the many things can be thought of as only one thing, and the one thing can be thought of as many things." It's heavy stuff. But 60s kids ate it up.

Fact-Checking the "Golden Age"

While we get misty-eyed about these classics, it’s worth noting that the industry wasn't perfect.

✨ Don't miss: Bird Feeders on a Pole: What Most People Get Wrong About Backyard Setups

Even as Ezra Jack Keats was breaking barriers, the majority of children's books from the 1960s were still overwhelmingly white and middle-class. It took the Council on Interracial Books for Children (founded in 1965) to really start pushing the industry to look at its own biases. We also see some themes in 60s books that haven't aged perfectly—certain gender roles in Dr. Seuss or the way "civilization" is portrayed in some adventure novels.

But the shift had started. The door was kicked open.

How to Curate a 1960s Library for a Modern Kid

If you’re looking to dive back into this world, don't just buy the "Top 10" lists. Look for the stuff that feels a bit experimental.

What to look for:

- The Original Hardcovers: If you can find the 1960s editions of the Narnia series (technically 50s but peaked in 60s popularity) or The Chronicles of Prydain by Lloyd Alexander, grab them. The cover art by people like Evaline Ness is incredible.

- The "I Can Read" Series: This was the heyday of the Harper & Row "I Can Read" books. Look for Little Bear or Frog and Toad (which technically started in 1970 but grew out of the 60s style).

- Poetry: This was when Shel Silverstein started getting weird. Lafcadio: The Lion Who Shot Back (1963) is a forgotten gem you should definitely track down.

- The "Newbery" Winners: Check the list of Newbery Medal winners from 1960 to 1969. You'll find gems like Island of the Blue Dolphins (1960) and Up a Road Slowly (1966).

The Legacy of the 1960s

Basically, the 1960s took the "kiddie book" and turned it into literature.

It was the decade where we decided that children could handle the truth. They could handle sadness, they could handle abstract art, and they could definitely handle a giant peach floating across the Atlantic. We moved from the "See Jane Run" simplicity of the Dick and Jane era into a world where a boy could be king of the monsters and still want to go home for dinner.

It's a legacy of empathy. And that never goes out of style.

Next Steps for Enthusiasts:

- Check Your Attic: Look for "First Edition" or "First Printing" markers on the copyright page of any 1960s-era books you own; certain titles like Where the Wild Things Are or A Wrinkle in Time can be worth thousands in good condition.

- Visit a Library Archive: Many university libraries (like the de Grummond Children's Literature Collection) hold the original manuscripts and layout sketches from 1960s illustrators.

- Cross-Reference the Caldecott Winners: Research the Caldecott Medal winners specifically from the years 1963–1969 to see the rapid evolution of print technology and color lithography during this decade.

- Compare Modern Reprints: When buying for children today, look for "anniversary editions" that restore the original 1960s color palettes, as many 1990s-era reprints used cheaper, de-saturated ink processes that don't capture the original pop-art vibrancy.