You’re sitting at your desk, scrolling through the news, and suddenly there’s a headline about a leak or a wildfire near a decommissioned plant. Your first instinct isn't to wait for the evening news. It's to see what’s actually happening in the air right now. That is exactly why the geiger counter world map has become a permanent tab for thousands of people globally. It’s a strange, pulsating digital grid of real-time anxiety and reassurance. It’s raw data, often crowdsourced, showing the invisible invisible particles moving through our atmosphere.

Radioactivity is scary because you can’t see it. You can’t smell it. But with a network of connected sensors, you can suddenly "see" it on a screen.

Most people think these maps are only for doomsday preppers or nuclear physicists. They aren't. They are for the curious, the cautious, and the people who live near places like Hanford, Sellafield, or Zaporizhzhia. It’s about transparency. When official government channels are slow—or let’s be honest, sometimes a bit vague—these maps provide a decentralized alternative that is hard to silence.

The Reality of Live Radiation Tracking

There isn’t just one single geiger counter world map that rules them all. Instead, we have a patchwork of different networks. Some are run by hobbyists with $100 sensors taped to their windowsills, while others are massive institutional projects.

Take Safecast, for instance. This is arguably the gold standard for open-source radiation data. It started right after the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi disaster because the Japanese government’s data was, at the time, confusing and incomplete. A group of volunteers realized they couldn't wait for "official" word. They built their own bGeigie Nano kits and started driving around. Today, Safecast has logged over 150 million data points. It’s massive. It’s messy. It’s beautiful. It’s also incredibly reliable because it’s peer-reviewed by the community.

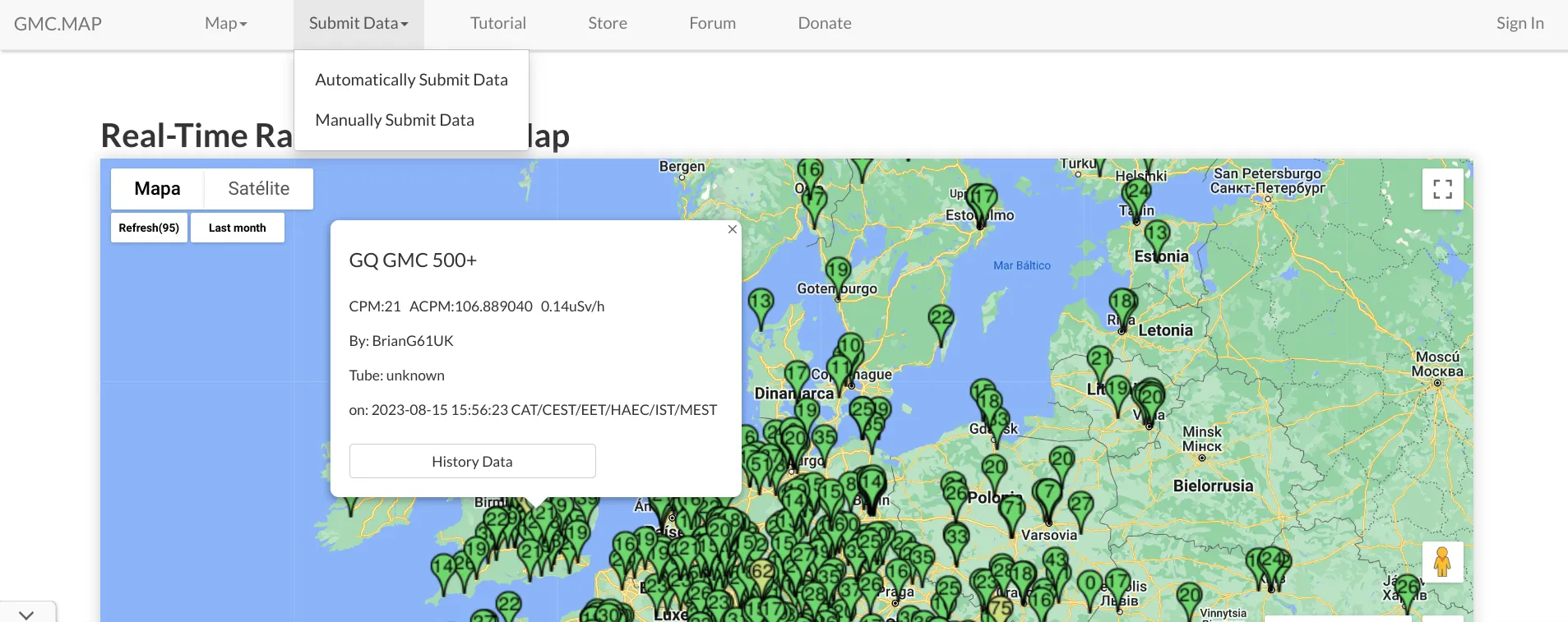

Then you have GMC Map, which is the playground for people who own GQ Electronics devices. If you buy a Geiger counter on Amazon, there’s a good chance it’s a GQ GMC model. These devices often have built-in Wi-Fi that pings a central server every few minutes. When you look at their map, you see thousands of dots globally.

Is it perfect? No.

Sometimes a sensor goes haywire. Or a cat knocks it over onto a piece of vintage uranium glass, making a local neighborhood look like it’s having a meltdown. That’s the nuance of crowdsourced data. You have to learn how to spot the outliers. One red dot in a sea of green is usually a technical glitch or a specific localized source—like someone testing a smoke detector—rather than a regional disaster.

📖 Related: Why Switching to New Outlook is Finally Worth the Hassle

Understanding the Units Without a Physics Degree

If you open a geiger counter world map, you’re going to see numbers followed by letters like uSv/h or CPM. It’s easy to panic when you see a number jump from 12 to 20. Don’t.

Basically, CPM stands for Counts Per Minute. It’s just the raw number of "clicks" the tube detects. It’s not a great way to measure health risks because different tubes have different sensitivities. A high-end pancake probe will click way more than a cheap glass tube, even in the same room.

The number you actually want to watch is uSv/h (microsieverts per hour). This is the "dose rate."

For context, a normal background radiation level in most parts of the world is somewhere between 0.05 and 0.20 uSv/h. If you’re in a plane at 35,000 feet, that number might jump to 2.0 or 3.0 uSv/h because there's less atmosphere to shield you from cosmic rays. Context matters. If you see a map showing 0.15 uSv/h, that’s just the Earth being the Earth. It’s the granite in the ground. It’s the sun. It’s normal.

Why We Are Obsessed With This Data

There is a psychological component to monitoring a geiger counter world map. It’s called "rad-watching."

For some, it’s a hobby similar to bird watching or tracking flights on FlightRadar24. For others, it’s a necessity born of trauma. People living in Northern Ukraine or near the 30km exclusion zone in Fukushima check these maps like others check the weather. It dictates if they open their windows or let their kids play in the dirt that day.

We also live in an era of information distrust. When the cloud from the Chernobyl disaster moved across Europe in 1986, many governments stayed silent for days. People were drinking contaminated milk while officials kept quiet to avoid "panic." The modern geiger counter world map makes that kind of information suppression nearly impossible. You can’t hide a radioactive plume when five hundred independent sensors in five different countries are all screaming at once.

It’s the ultimate "check and balance" for the nuclear age.

The Technical Hurdles of Making a Global Map

Building a geiger counter world map is actually a nightmare from a data engineering perspective.

First, there’s the hardware. Most consumer Geiger counters use a Geiger-Müller tube filled with low-pressure gas. When radiation hits the tube, it ionizes the gas, creating a pulse of electricity. These tubes age. They get "poisoned." They lose sensitivity. If a map is using data from five-year-old sensors that haven't been calibrated, the map is lying to you.

Second, there is the "Heat Island" effect, but for radiation. Certain cities are built on high-radon soil or use a lot of granite in their architecture. If you put a sensor in a basement in Cornwall, UK, it’s going to read much higher than a sensor in a wooden house in Florida.

Third, weather plays a massive role. Rain "washes" radioactive isotopes (like Radon daughters) out of the sky. This is called a "Radon Washout." After a heavy rainstorm, you will almost always see a spike on a geiger counter world map. Amateurs often freak out and think there’s been an accident, but experienced users just see it as a rainy Tuesday.

Major Networks You Should Actually Follow

If you want to dive into this, don't just Google "radiation map" and click the first link. Most of those are SEO-spam sites that haven't updated since 2018. Stick to the live networks.

📖 Related: Alphanumeric Characters: Why This Boring Technical Term Actually Rules Your Life

- RadonMap.com: Great for indoor air quality, which is actually a much bigger health threat to the average person than a nuclear plant.

- EURDEP (European Radiological Data Exchange Platform): This is the "official" one for Europe. It aggregates data from national monitoring stations. It’s very reliable but sometimes has a lag because the data has to be "validated" by government bureaucrats first.

- Radioactivity.nscl.msu.edu: Often used by researchers to track environmental changes.

- uRadMonitor: This is a global network of "Iot" (Internet of Things) sensors. They don't just track radiation; they track air quality, CO2, and noise. It’s a holistic look at the environment.

The Limitations of Crowdsourced Maps

We have to talk about the "expert vs. amateur" divide. A scientist from the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) might look at a geiger counter world map and roll their eyes. Why? Because these maps don't usually distinguish between types of radiation.

Is it Alpha, Beta, or Gamma? A standard Geiger counter usually only measures Gamma and sometimes high-energy Beta. It won't tell you if there’s Alpha-emitting dust in the air unless you have a very specific (and expensive) pancake probe.

Also, these maps don't tell you what isotope is being detected. Is it Iodine-131, which is a sign of a fresh reactor leak? Or is it just a high concentration of Radon-222? Without a gamma spectrometer—a device that costs thousands and requires a PhD to read the results—you’re just seeing "how much," not "what."

Despite these flaws, the sheer volume of data on a geiger counter world map provides a "safety in numbers" effect. If 200 sensors in Poland all show a 15% increase in background radiation over a 2-hour window, something happened. You don't need a lab-grade analysis to know it's time to start asking questions.

How to Get Involved Without Being a Scientist

You can actually join these networks. You don't need to be a physicist.

Buying a "cloud-ready" Geiger counter is the easiest way. Devices like the GQ GMC-500+ or the uRadMonitor Model A3 are basically plug-and-play. You connect them to your home Wi-Fi, and they automatically start feeding data into the global geiger counter world map.

It’s a weirdly satisfying feeling. You are a data point. You are a sentinel.

For the DIY crowd, the Safecast bGeigie is a fun project. It requires some soldering and assembly, but it’s a ruggedized unit that you can strap to your car or bike. This "mobile" data is actually more valuable than stationary data because it helps map out "hot spots" in neighborhoods that stationary sensors might miss.

💡 You might also like: Why Is Instagram So Racist? What Most People Get Wrong

Actionable Steps for Using Radiation Maps Effectively

If you're going to start using a geiger counter world map regularly, do it the right way. Don't be the person who panics over every tiny spike.

First, establish a baseline. Check the map when everything is normal. Look at the sensors near your home or office. What is their "quiet" number? Usually, it's between 0.10 and 0.18 uSv/h. Once you know what "normal" looks like, you can easily spot an actual anomaly.

Second, cross-reference. Never trust a single sensor. If you see a high reading on one map, check a different network. If GMC Map shows a spike but Safecast and the official government sensors don't, it’s almost certainly a local issue with that specific device—maybe the owner is doing a test or the battery is dying.

Third, watch the weather. Before you assume the worst, check if it just rained. Rain is the number one cause of "false" radiation alarms on these maps.

Fourth, understand the geography. Are you near a coal plant? Coal plants actually release more radiation into the immediate environment than nuclear plants during normal operation because coal contains trace amounts of uranium and thorium that get concentrated in the fly ash. This can show up on sensitive maps.

Finally, keep a cool head. Radioactive isotopes have half-lives. Some, like Iodine-131, disappear in weeks. Others, like Cesium-137, stay for decades. A geiger counter world map is a tool for situational awareness, not a reason to live in a bunker. Use it to stay informed, to hold institutions accountable, and to satisfy your curiosity about the invisible world around us.

The data is out there. It’s live, it’s raw, and it’s accessible to anyone with an internet connection. Knowing how to read it is the difference between being a victim of rumors and being a master of your own environment. Stay curious, keep an eye on the sensors, and remember that knowledge is the best shield against the unknown.