Charlie Chaplin was terrified. Honestly, he had every reason to be. By 1937, the world was watching Adolf Hitler with a mix of paralyzed dread and, strangely enough, a bit of awkward curiosity. But Chaplin? He saw something else. He saw a man who had "stolen" his mustache. He saw a clown playing with the fate of humanity. So, he decided to make the Charlie Chaplin dictator film that everyone told him would ruin his career. The Great Dictator wasn't just a movie; it was a middle finger to fascism delivered by a guy who usually spent his time falling into manholes.

It's wild to think about now. At the time, the United States was still strictly isolationist. Hollywood was terrified of losing the German market. The British government even sent word that they’d likely ban the film to avoid upsetting Hitler. But Chaplin put $2 million of his own money—equivalent to a small fortune today—into the production. He didn't care.

The Mustache Wars and the Two Men Born in 1889

There is this weird, almost cosmic coincidence that links Chaplin and Hitler. They were born just four days apart in April 1889. Both came from poverty. Both rose to become two of the most recognizable faces on the planet. And, of course, they shared the toothbrush mustache.

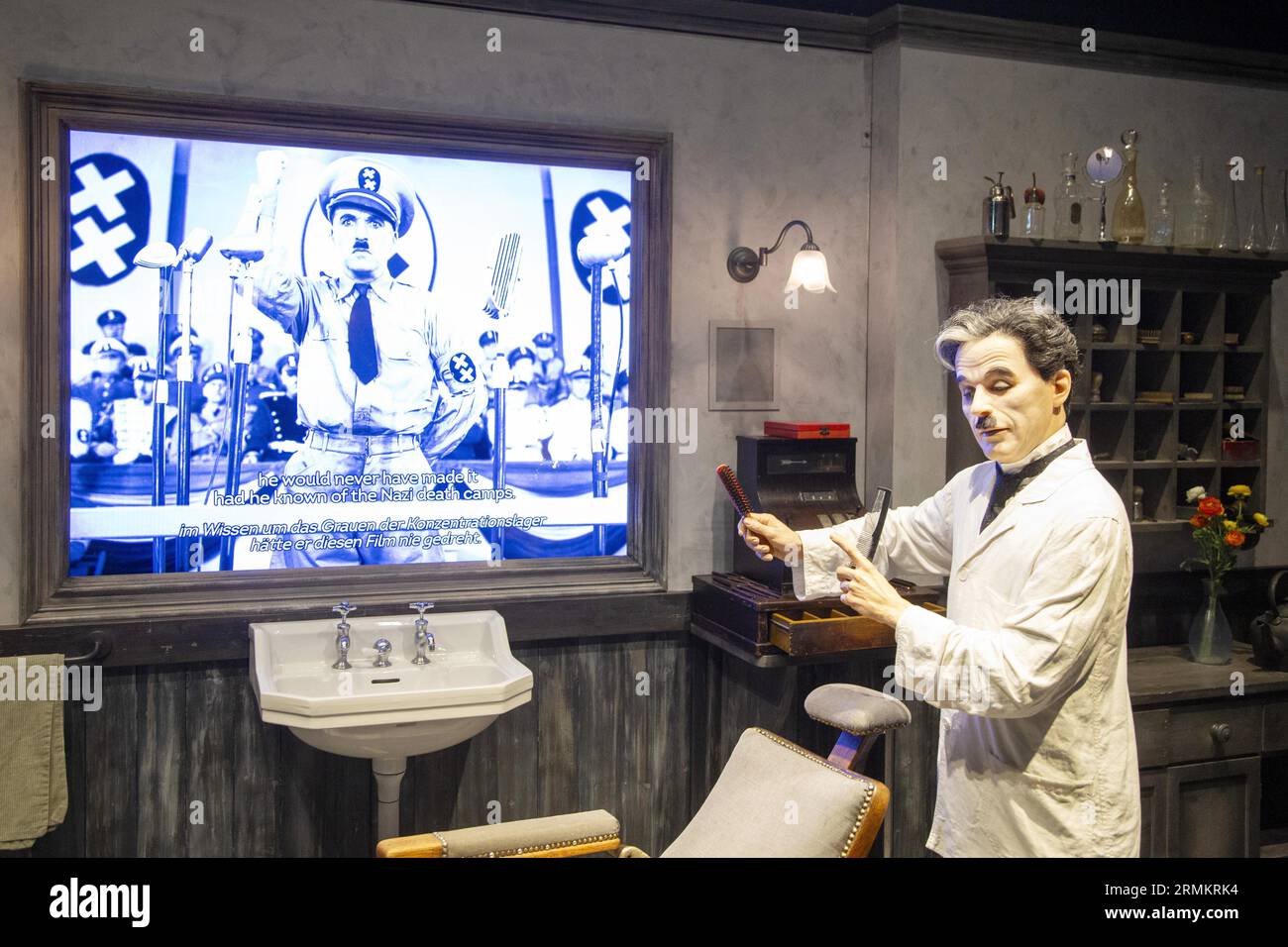

Chaplin knew this. He reportedly felt that Hitler was a "bogus" version of himself. While Hitler used his persona to project power, Chaplin used his to highlight the struggles of the common man. When production on the Charlie Chaplin dictator film began, the world was a powder keg. Chaplin played two roles: a Jewish barber with amnesia and Adenoid Hynkel, the Dictator of Tomania.

It was his first true "talkie." For years, Chaplin resisted sound. He thought his Little Tramp character would die if he ever spoke. But for this story, silence wasn't enough. He needed to scream. He needed to mock the rhythmic, guttural barking of Hitler's speeches. If you watch the scene where Hynkel gives a speech in "Tomanian," it's pure gibberish. But it sounds like hatred. It’s a masterclass in how performance can strip a tyrant of his dignity.

Why Hollywood Wanted Him to Stop

You have to understand the climate of 1938. The "Production Code" was in full swing, and Joseph Breen, the man who enforced it, was leaning hard on Chaplin. The Hays Office warned him that he was asking for trouble. Even United Artists, the company Chaplin helped found, was sweating. They were worried about censorship. They were worried about riots.

But then something shifted.

🔗 Read more: How Old Is Paul Heyman? The Real Story of Wrestling’s Greatest Mind

As the film was being edited, the Nazis invaded Poland. Suddenly, the "wait and see" approach to Hitler was dead. The British, who had previously threatened to ban the film, realized they needed it. They needed a weapon of morale. Chaplin later said in his autobiography that if he had known the true extent of the horrors in the concentration camps, he could never have made the film. He couldn't have made fun of that kind of homicidal insanity. But at the time, he only knew what the world knew: Hitler was a bully who needed to be laughed at.

That Final Speech: A Six-Minute Miracle

If you’ve seen the Charlie Chaplin dictator film, you know the ending. It’s famous. It’s controversial. It’s long. The Jewish barber is mistaken for Hynkel and is forced to address a massive military rally. Instead of preaching hate, he delivers a plea for humanity.

"I don’t want to be an emperor," he says.

Some critics at the time hated it. They thought it broke the "fourth wall" too much. They felt it was Chaplin stepping out of character to lecture the audience. But that was exactly the point. Chaplin wasn't being a barber or a tramp anymore. He was being a human.

The speech is over 700 words long. In an age of TikTok reels, that sounds like an eternity. But in 1940, it was oxygen. He talks about how "the misery that is now upon us is but the passing of greed." He calls for a world where science and progress lead to all men's happiness.

- It was filmed in late 1940.

- The shot is almost entirely a static close-up.

- Chaplin's voice shakes with genuine emotion.

- The score swells, but the words do the heavy lifting.

Even now, people remix that speech. They put it over Hans Zimmer music or use it in political protests. It has outlived the film's parody because it hits on a universal truth: we have developed speed, but we have shut ourselves in.

💡 You might also like: Howie Mandel Cupcake Picture: What Really Happened With That Viral Post

The Backlash Nobody Talks About

While the film was a massive box office success—the biggest of Chaplin's career—it also marked the beginning of his downfall in America. The FBI, under J. Edgar Hoover, started keeping a file on him. They thought the speech was "pro-Communist." They hated that he was a British citizen living in the U.S. who was "stirring up" political trouble.

The Charlie Chaplin dictator film made him a hero to the public but an enemy to the state. By the early 1950s, Chaplin was essentially exiled from the United States. When he left for a trip to London, the government revoked his re-entry permit. All because he dared to speak his mind when others were too scared to whisper.

It's kinda wild how one movie can define a life. It was his greatest triumph and the start of his greatest tragedy.

The Ball and the Globe

You can't talk about The Great Dictator without mentioning the globe dance. It’s arguably the most famous scene in cinema history. Hynkel dances with an inflatable globe, tossing it into the air, bouncing it off his backside, and treating the world like a delicate toy.

It’s beautiful and horrifying at the same time. It captures the narcissism of a dictator perfectly. To Hynkel, the world isn't a place where people live; it's a plaything. When the balloon eventually pops in his face, the look of devastated, childish sadness is brilliant. It’s a reminder that these "great men" are often just toddlers with too much power.

Why You Should Care Today

Most movies from 1940 feel like museum pieces. They’re slow. The acting is theatrical. But the Charlie Chaplin dictator film feels weirdly modern. The satire of media manipulation, the way Hynkel poses for photos while planning invasions, and the tension between technology and human kindness—it’s all still happening.

📖 Related: Austin & Ally Maddie Ziegler Episode: What Really Happened in Homework & Hidden Talents

If you’re a film student or just someone who likes a good story, look at the cinematography. Chaplin wasn't known for being a visual innovator in terms of camera movement, but the framing in the Tomanian palace is meant to make Hynkel look small in a big room. It’s subtle psychology.

Practical Steps to Appreciate the Work

If you want to actually "get" why this movie matters, don't just watch the clips on YouTube. You need the context.

- Watch the "Speech" last. If you watch it out of context, it’s just a nice monologue. If you watch it after seeing 90 minutes of the barber's suffering, it’ll make you cry.

- Read the FBI files. You can actually find the declassified documents online. Seeing how the government tracked Chaplin because of this film is eye-opening.

- Compare the Barber to the Tramp. Notice the subtle differences. The Barber has a home, a job, and a name (eventually). The Tramp was a ghost. This film was Chaplin's way of giving the Tramp a soul and then letting him go.

The Charlie Chaplin dictator film didn't stop World War II. It didn't kill Hitler. But it did something else. It proved that a small man with a funny walk could stand up to the most terrifying force on earth and make it look ridiculous. In the end, laughter is the one thing a dictator can't survive.

When you look at the history of cinema, there are "great" movies and then there are "important" movies. This one is both. It’s a testament to the idea that art shouldn't just reflect the world—it should try to save it. Even if it fails, the attempt is what makes us human.

If you're looking for a starting point for classic cinema, this is it. It’s funny, it’s heartbreaking, and it’s unapologetically loud about what it believes in. Chaplin risked everything for it. The least we can do is keep watching.

Actionable Insights:

- Study the Parody: If you are a writer or creator, watch how Chaplin uses "Grammelot" (gibberish) to satirize authoritarian speech patterns without using a single real word of hate.

- Contextualize History: Pair a viewing of the film with a reading of 1939-1940 newspapers to see just how radical Chaplin’s stance was during the period of American neutrality.

- Analyze the Transition: Use this film as a case study for how an artist can transition from silent performance to dialogue while maintaining their core identity.