You think you know Cinderella. You probably picture a pumpkin turning into a carriage, some singing mice, and a sparkly blue dress. Honestly, though? The version of charles perrault fairy tales that most of us grew up with is a heavily filtered, sugar-coated ghost of the original 1697 text. Charles Perrault wasn't some kindly old grandpa writing bedtime stories for toddlers. He was a high-ranking French civil servant and a member of the Académie Française who wrote for the sophisticated, cynical salons of Louis XIV’s Versailles.

He was writing for adults. High-society adults who loved gossip, fashion, and sharp wit.

When Perrault published Histoires ou contes du temps passé, he wasn't just "recording" folklore. He was transforming oral peasant traditions into "literary" tales, complete with rhyming morals that often felt more like social warnings than "happily ever afters." If you go back to the original source, you’ll find that these stories are less about magic and more about the brutal realities of 17th-century power dynamics, marriage, and survival.

The Man Behind the Mother Goose

Charles Perrault was a bit of a disruptor. In the 1680s, he sparked the "Quarrel of the Ancients and the Moderns," arguing that modern French literature was actually better than the classics of Greece and Rome. It was a bold move. Writing down "low-brow" folk tales was his way of proving that simple, French stories could be just as impactful as Homer or Virgil.

He didn't even put his own name on the book initially. He used his son’s name, Pierre Darmancour. Why? Because a serious intellectual like Perrault wasn't supposed to be messing around with stories about talking wolves and glass slippers. But the book became a massive hit. Suddenly, the French court was obsessed with "contes de fées."

The Glass Slipper and the Problem with Cinderella

People love to argue about the slipper. You might have heard the popular theory that it was originally "vair" (squirrel fur) and Perrault mistook it for "verre" (glass).

It’s a fun myth. It’s also wrong.

🔗 Read more: The Name of This Band Is Talking Heads: Why This Live Album Still Beats the Studio Records

Scholars like Anatole France and later folklorists have largely debunked the "fur slipper" theory. Perrault chose glass specifically because it was a luxury item in the 1600s. Glass was fragile, expensive, and impossible to stretch. It was a litmus test for the perfect, dainty aristocratic foot. In charles perrault fairy tales, the glass slipper is a symbol of fragility and elite status.

But look at the ending. In the Perrault version, Cinderella doesn't just get the prince. She finds noble husbands for her two sisters. It’s a political move. She secures her family's future through strategic marriages, which was the ultimate goal for any woman in the court of Louis XIV. The "moral" Perrault adds at the end suggests that while beauty is great, "bonne grâce" (graciousness or charm) is the real currency of the world. Basically, you can be pretty, but if you aren't charming and well-connected, you're going nowhere.

Sleeping Beauty: A Tale of Two Halves

Most movies end with the kiss. In the original charles perrault fairy tales, the kiss is just the halfway point.

The Prince and Princess get married in secret. They have two kids named Morning and Day. But there’s a problem: the Prince’s mother is an Ogre. No, literally. She’s part Ogre and has a physical craving for human flesh. When the Prince becomes King and goes off to war, the Queen Mother decides she wants to eat her grandchildren with a nice sauce robert.

It gets incredibly grim. The cook hides the children and serves the Ogress a lamb instead. Eventually, the King returns just as his mother is about to throw the Princess and the kids into a tub full of toads and vipers. The Ogress, seeing she’s been caught, jumps into the viper tub herself and is consumed.

It’s a wild tonal shift. It reminds the reader that marriage isn't the end of the struggle; it’s often just the beginning of dealing with a nightmare mother-in-law.

💡 You might also like: Wrong Address: Why This Nigerian Drama Is Still Sparking Conversations

Red Riding Hood and the Absence of the Woodsman

If you want to see how Perrault differs from the Brothers Grimm, look at Little Red Riding Hood.

In the Grimm version, a heroic woodsman cuts the wolf open and saves everyone. Everyone lives. Yay.

In Perrault’s 1697 version? The wolf eats the girl. The story ends. No rescue. No second chances.

Perrault’s moral is startlingly blunt. He writes that "well-bred young ladies" shouldn't listen to strangers, because "of all the wolves, the most dangerous are those who are charming, quiet, and polite." He was warning the girls of the French court about "wolves" in silk stockings—predatory men who used sweet words to ruin reputations.

It’s dark. It’s cynical. It’s very 17th-century Paris.

Bluebeard: The Horror of Curiosity

Bluebeard is arguably the most famous of the charles perrault fairy tales that hasn't been "Disneyfied." It’s a straight-up horror story. A wealthy man with a blue beard marries a young woman and gives her the keys to his entire estate, but forbids her from entering one specific room.

📖 Related: Who was the voice of Yoda? The real story behind the Jedi Master

She enters it, of course. She finds the floor covered in blood and the bodies of his previous wives hanging on the walls.

The key she drops is enchanted; the bloodstain won't wash off, tipping Bluebeard off to her betrayal. This story is often cited by feminist scholars like Maria Tatar as a commentary on "female curiosity" and the dangers of marriage in an era where men had absolute legal power over their wives' lives. Perrault’s moral is a bit tongue-in-cheek here, suggesting that curiosity brings "a thousand regrets," but he also mocks the idea that modern men are as terrible as Bluebeard. He was playing both sides.

Why These Stories Refuse to Die

Perrault’s influence is everywhere. He gave us the "fairy godmother." He gave us the "wicked stepmother" trope in its most polished form. Before him, folk tales were wandering, messy things. He gave them structure, wit, and a specifically urban, sophisticated flair.

He also understood the power of the "forbidden." Whether it’s a locked room, a spinning wheel, or a strange wolf in a bed, his stories tap into fundamental human anxieties.

The reason charles perrault fairy tales still matter in 2026 isn't just nostalgia. It’s because they aren't actually for children. They are maps of human behavior. They show us how people use power, how they navigate social hierarchies, and how they survive in a world that is often predatory and unfair.

How to Approach the Original Texts Today

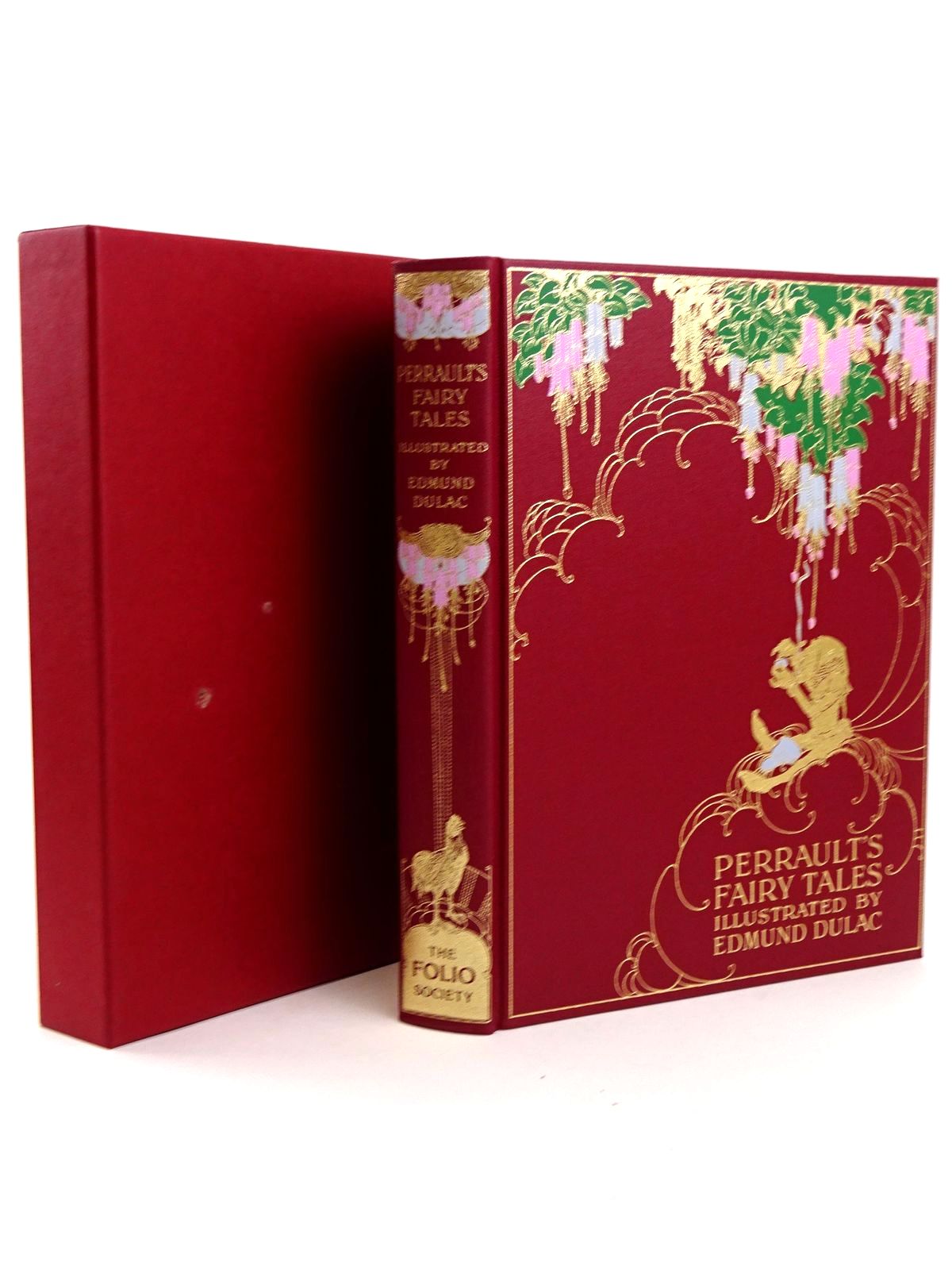

If you're looking to actually dive into these, don't just grab a random "Fairy Tale" book from the bargain bin. Those are almost always edited to be "safe."

- Find a Complete Translation: Look for the Christopher Betts translation (Oxford World's Classics). It keeps the verses and the biting wit of the original French.

- Read the Morals: Never skip the rhyming poems at the end. That’s where Perrault reveals his true intent—often mocking the very characters he just wrote about.

- Compare with the Brothers Grimm: Notice how the Germans (Grimm) made the stories more nationalistic and violent, while the Frenchman (Perrault) made them more about etiquette and social maneuvering.

- Look for the Fashion: Pay attention to the descriptions of clothes. In Puss in Boots, the cat’s boots are a sign of his transition from animal to "person of quality." In Perrault's world, clothes don't just make the man; they make the human.

The real Charles Perrault is much more interesting than the "Mother Goose" caricature. He was a man who saw the world as a dangerous, glittering ballroom where one wrong step could lead to disaster—and he wrote these stories to make sure we knew exactly where the traps were hidden.

Actionable Insight: To truly understand the evolution of Western storytelling, compare Perrault’s Cinderella with the version by the Brothers Grimm. You will notice that Perrault’s version is focused on social grace and class ascent, whereas the Grimm version is far more focused on "blood-and-bone" justice and divine punishment. Understanding this shift helps you see how different cultures used the same "bones" of a story to teach completely different social values.