You’ve probably seen it in a vintage shop or a history textbook. A tiny, palm-sized vinyl cover in a shade of red so bright it practically vibrates. It’s officially titled Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung, but the world knows it simply as Chairman Mao's Little Red Book.

It’s weird to think about a book as a weapon. But that’s exactly what it was. During the height of the Cultural Revolution in China, not carrying this book wasn't just a social faux pas; it was a physical risk. If you couldn't wave it in the air or recite a passage on command, you were asking for trouble.

We’re talking about a text that reached a print run of over a billion copies. Some estimates say five billion. To put that in perspective, it’s rivaled only by the Bible. Yet, despite its massive global footprint, most people today have no idea what’s actually written inside those 400-odd pages.

The Birth of a Secular Bible

The book didn't start as a grand philosophical manifesto. Not even close. It actually began as an internal training manual for the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) in 1964. Lin Biao, the head of the military at the time and Mao’s "hand-picked" successor (until he wasn't), wanted a way to indoctrinate soldiers quickly. He figured long, dry essays on Marxist theory were too much for the average recruit.

So, they chopped up Mao’s old speeches and writings into bite-sized snippets.

It was basically Twitter before Twitter existed. Short. Punchy. Easy to memorize.

By 1966, as the Cultural Revolution kicked into high gear, the book migrated from the barracks to the streets. The Communist Party basically mandated that every citizen own one. Factories churned them out in dozens of sizes, though the "vest pocket" version was the gold standard because it meant you were always ready for a spontaneous study session.

What’s Actually Inside the Red Vinyl?

If you pick one up today, the first thing you'll notice is how the content is organized. It’s not a narrative. It’s 427 quotations divided into 33 thematic chapters.

The topics range from the "Mass Line" to "Correcting Mistaken Ideas." Some of it is surprisingly common-sense advice about discipline, while other parts are chillingly radical.

"Revolution is not a dinner party, or writing an essay, or painting a picture, or doing embroidery; it cannot be so refined, so leisurely and gentle, so temperate, kind, courteous, restrained and magnanimous. A revolution is an insurrection, an act of violence by which one class overthrows another."

👉 See also: Why are US flags at half staff today and who actually makes that call?

That’s perhaps the most famous quote in the whole collection. It set the tone for a decade of chaos. You have to understand the psychological weight of these words at the time. For a Red Guard—the student paramilitaries who idolized Mao—this wasn't just political theory. It was a permission slip.

The book covers:

- The Communist Party: Why the party is the "core" of the Chinese people.

- Classes and Class Struggle: The idea that society is in a constant state of internal war.

- War and Peace: Mao’s famous dictum that "political power grows out of the barrel of a gun."

- Self-Criticism: A section that fueled the infamous "struggle sessions" where people were publicly humiliated for perceived ideological failings.

It’s a mix of military strategy and moral guidance. Honestly, it reads a bit like a handbook for a total societal reset.

Why Did It Become Such a Global Phenomenon?

You might think Chairman Mao's Little Red Book was strictly a Chinese obsession. You’d be wrong. In the late 1960s, it became the ultimate accessory for the radical left in the West.

From the Black Panthers in Oakland to student protesters in Paris, the book was everywhere. Huey P. Newton, co-founder of the Black Panther Party, actually bought copies of the book in bulk from a Chinese bookstore in San Francisco to sell to students at UC Berkeley. He used the profits to buy guns.

Talk about a bizarre circle of commerce.

For Western radicals, the book represented a "Third Way." They were disillusioned with the Soviet Union’s stale bureaucracy and disgusted by Western capitalism. Maoism felt fresh. It felt active. The book offered a DIY guide to revolution that felt more accessible than the dense volumes of Karl Marx’s Das Kapital.

Of course, there was a massive disconnect. The students in Paris were reading about "protracted people's war" while sitting in cafes. In China, those same words were being used to justify the destruction of ancient temples and the persecution of teachers and intellectuals.

The Visual Power of the "Red Sea"

One reason the book sticks in our collective memory is the imagery. If you look at archival footage from the 1960s, you see thousands of people rhythmically waving the book toward the sky.

✨ Don't miss: Elecciones en Honduras 2025: ¿Quién va ganando realmente según los últimos datos?

This was the "Red Sea."

The book became a prop. It was used in dance (the "loyalty dance"), in sports, and even in surgery. There are actual accounts of doctors and patients reciting Mao’s quotes together before an operation to ensure its success.

It’s hard for a modern mind to grasp that level of total immersion. Imagine if every time you had a question, every time you felt doubt, and every time you met a stranger, you both looked at the same 400 quotes for the answer. It creates a terrifyingly unified reality.

The Collapse of the Cult

Nothing lasts forever. Especially not a cult of personality built on a pocket-sized book.

When Mao died in 1976 and the "Gang of Four" was arrested, the fever broke. Suddenly, the book that had been a mandatory life-accessory became a liability. People started hiding them. Burning them. Selling them to recyclers.

The new leadership under Deng Xiaoping wanted to move toward "Socialism with Chinese characteristics," which basically meant focusing on the economy rather than constant class struggle. The Little Red Book didn't fit the new vibe.

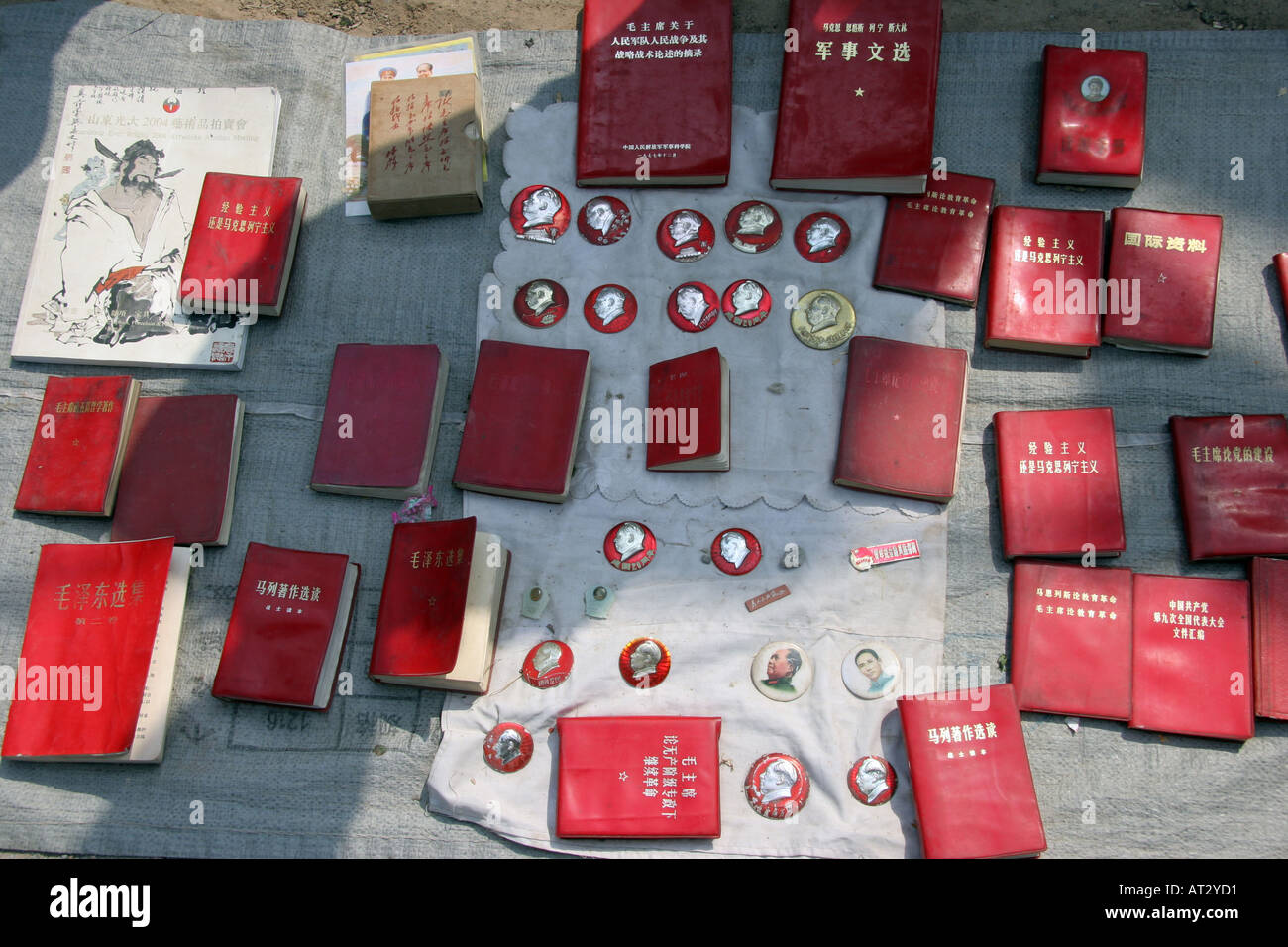

Today, the book exists in a weird limbo. In China, you can find it in souvenir stalls near Tiananmen Square, sold alongside Mao-themed lighters and badges. It’s been commodified. It’s kitsch.

But for those who lived through the Cultural Revolution, the sight of the book can still trigger a visceral reaction. It represents a "ten years of madness" that reshaped China’s DNA.

Nuance and Misconceptions

People often assume everyone in China loved the book. That’s a simplification. For many, carrying it was a survival strategy. If you didn't have it, you were a target. If you dropped it, you were a counter-revolutionary.

🔗 Read more: Trump Approval Rating State Map: Why the Red-Blue Divide is Moving

There are stories of people accidentally wrapping groceries in old newspaper that happened to have Mao’s face or a quote on it. That was enough to get you sent to a labor camp. The book wasn't just a book; it was a physical manifestation of Mao himself.

Also, it’s a mistake to think Mao wrote every word for this specific book. He didn't. He was a prolific writer, but the Quotations are heavily edited snippets taken out of context. By stripping away the historical context of his original essays, the editors made the ideas more absolute—and more dangerous.

Real-World Impact: The Numbers

To grasp the scale, look at the distribution. By the end of 1967, the official count was 350 million copies printed. By the time the madness subsided, the Foreign Languages Press had translated it into dozens of languages, including Esperanto.

The logistics required to produce this many books were staggering. It actually caused a paper shortage in China. The government had to prioritize the book over almost all other forms of publishing. For a few years, China was essentially a one-book nation.

How to Understand the Book Today

If you’re interested in history, politics, or even marketing, there’s a lot to learn from the Little Red Book.

First, it’s a masterclass in branding. The color, the size, the repetitive messaging—it’s the most successful propaganda campaign in human history.

Second, it shows how easily "common sense" can be weaponized. Many of the quotes in the book sound reasonable in a vacuum. "Be modest and prudent," Mao says. "Learn from the masses." But when those platitudes are backed by a state with total control, they become tools for monitoring behavior.

If you want to dive deeper into this era, I’d suggest looking at the work of historian Frank Dikötter, specifically The Cultural Revolution: A People's History. He does a great job of stripping away the myths and showing the human cost of the policies found in the Little Red Book.

Another great resource is the memoir Wild Swans by Jung Chang. It gives a raw, personal account of how the mandates in the book actually played out in the lives of three generations of women.

Actionable Steps for the Curious

If you're looking to understand the legacy of Chairman Mao's Little Red Book without getting lost in the weeds, here is how you should approach it:

- Read it as a primary source, not a textbook. Don't expect a cohesive history of China. Read it to see what kind of language was used to mobilize an entire generation.

- Compare different editions. The early PLA versions are different from the ones exported to the West. The "Introduction" by Lin Biao was later torn out of millions of copies after he fell out of favor and died in a mysterious plane crash. Finding a copy with the Lin Biao intro intact is a collector's dream.

- Visit the "Maoist" kitsch markets if you're in Beijing. But remember that for the people selling them, it's a business. For their parents, it was a religion.

- Study the graphic design. The posters and art associated with the book are some of the most influential works of 20th-century graphic design. Look for the "Propaganda Poster Art Centre" in Shanghai if you ever get the chance.

The Little Red Book isn't just a relic. It's a reminder of what happens when a single set of ideas is allowed to crowd out everything else. It's a fascinatng, terrifying, and essential piece of global history that explains a lot about where China is today—and where it might be going.