Tatsuki Fujimoto is a weird guy. If you’ve read Chainsaw Man, you already know that. It’s a manga that breathes chaos, fueled by a mangaka who once uploaded a video of himself trying to levitate. So, when people start talking about chainsaw man fan service, they usually expect the standard shonen tropes. You know the ones. The accidental trips, the convenient steam in hot spring episodes, and the exaggerated proportions that have defined the genre for decades.

But Fujimoto doesn't play by those rules.

In Chainsaw Man, "fan service" is often a trap. It’s a bait-and-switch that uses the protagonist's horniness—and by extension, the reader's expectations—to punch you directly in the gut. Denji’s motivations are famously shallow. He wants to touch a breast. He wants to kiss a girl. He wants to eat good food. On the surface, it looks like the series is leaning into cheap thrills, but it’s actually a deconstruction of how desire can be used to manipulate and break a human being.

The Makima Factor: Power and Predation

Makima is the center of the chainsaw man fan service debate, and for good reason. From her first appearance, she is framed through Denji’s eyes as the ultimate object of desire. She’s beautiful, mysterious, and seemingly kind. For many readers, she became an instant "waifu" figure.

However, if you look closer at the framing, it’s rarely about sexualization for the sake of the audience. It’s about power. Every "fan service" moment involving Makima is a calculated move to bind Denji to her. Think about the scene where she allows Denji to touch her chest. In any other shonen, this would be a high-octane comedy moment or a simple reward. In Chainsaw Man, it’s a clinical, almost eerie demonstration of control. She uses his touch to ground him to her will, turning a moment of physical intimacy into a contract of subservience.

It's uncomfortable. It's supposed to be.

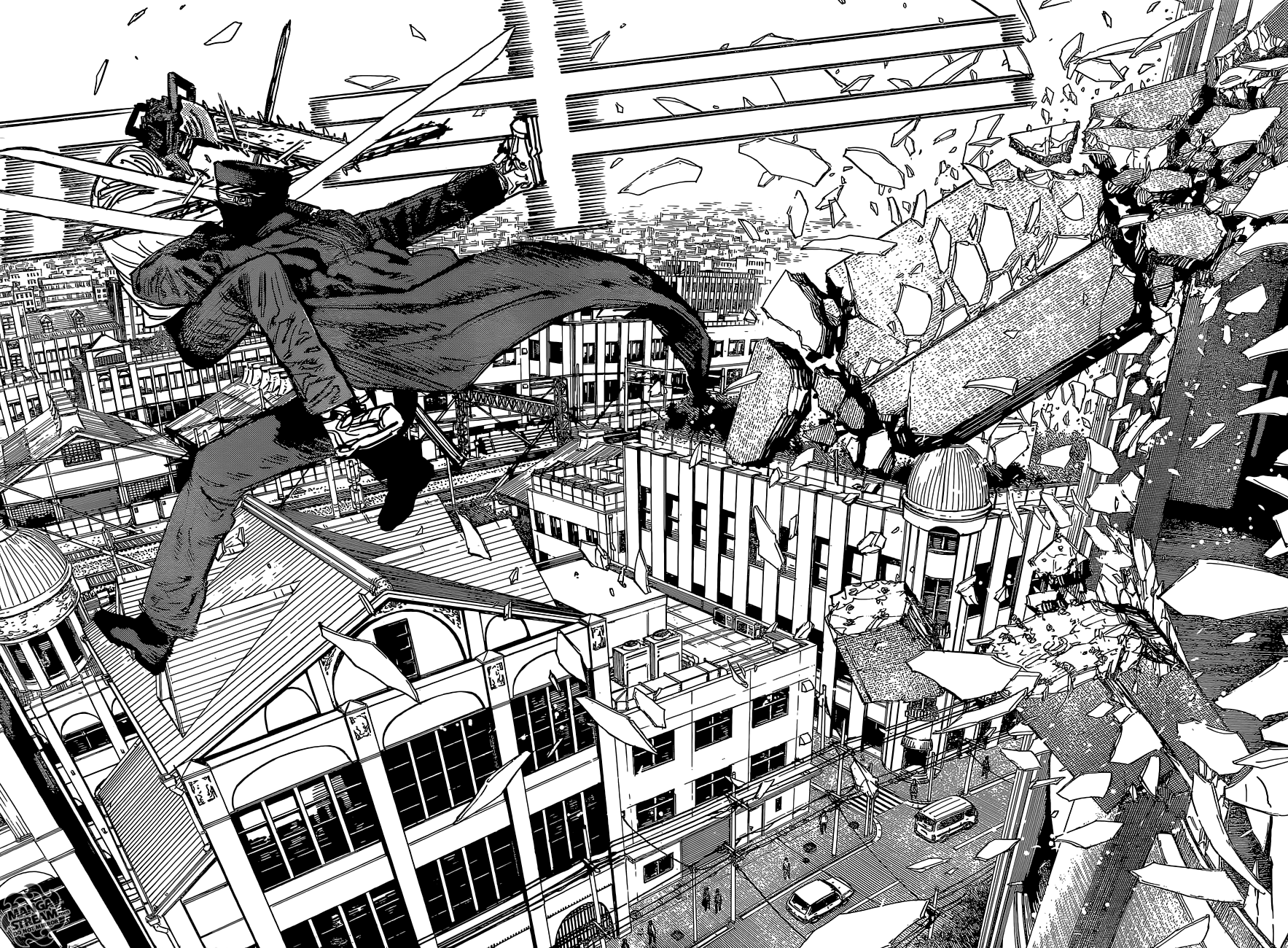

Fujimoto uses the visual language of fan service to highlight Denji's vulnerability. He’s a kid who has never known affection. To him, these scraps of physical contact are everything. To Makima, they are tools. When the anime adaptation by MAPPA arrived, directed by Ryu Nakayama, this cinematic approach became even more pronounced. The "fan service" wasn't bouncy or bright; it was captured with a realistic, almost voyeuristic lens that made the power imbalance feel heavy and realistic.

Denji’s Quest and the Emptiness of the Prize

Denji is basically the personification of the teenage male gaze, but the story constantly mocks the idea that fulfilling those desires leads to happiness.

💡 You might also like: Is Steven Weber Leaving Chicago Med? What Really Happened With Dean Archer

Take the infamous "kiss" scene during the Eternity Devil arc. It’s built up as a classic shonen milestone. Denji is finally going to get his reward. The framing is tight, the music builds, and then—reality hits. Himeno vomits into his mouth. It’s gross. It’s visceral. It’s the exact opposite of what "fan service" is supposed to provide.

This is the core of Fujimoto’s philosophy. He gives the audience (and Denji) what they think they want, then shows them the messy, disgusting, or heartbreaking reality behind it.

Why Power Breaks the Mold

Then there’s Power. If Makima is the predatory side of desire, Power is the subversion of the "best girl" trope. She’s loud, she doesn't bathe, she lies constantly, and she has no sense of human boundaries.

The scene where Power asks Denji to feel her chest after he saves Meowy is a perfect example of how chainsaw man fan service works differently. Denji spends chapters obsessing over this moment. It’s his North Star. But when it actually happens? He feels nothing. It’s empty.

"The more I think about it, the more I realize that the things I wanted weren't actually that great." — Denji (Paraphrased)

This realization is a turning point for the character. It shifts his motivation from purely physical gratification to a search for actual emotional connection. Fujimoto uses the imagery of fan service to show that the physical act, divorced from genuine intimacy, is just "meat." It’s a bold move for a magazine like Weekly Shonen Jump, which usually thrives on the very tropes Fujimoto is dismantling.

Male Objectification? The "Beam" and "Kishibe" Effect

Interestingly, the series doesn't just focus on the female cast. There’s a certain level of "fan service" directed toward the male characters, though it’s usually draped in blood or trauma.

📖 Related: Is Heroes and Villains Legit? What You Need to Know Before Buying

Aki Hayakawa, for instance, is frequently shown in domestic settings—showering, tying his hair, smoking on a balcony. These moments are quiet and aesthetic, appealing to a different side of the fanbase. But even here, the "service" is tied to his mortality. We watch him because we know his time is running out. We’re being sold his beauty so that his eventual fate hurts more.

Then you have characters like Beam, the Shark Fiend, who is purely motivated by his devotion to "Lord Chainsaw." His fan service is his loyalty and his absurd, shirtless design, serving as a comedic foil to the grim reality of the other Devil Hunters.

The MAPPA Aesthetic: Realism vs. Fantasy

When the Chainsaw Man anime launched, the community had a meltdown over the "cinematic" style. Some fans wanted the exaggerated, colorful look of the manga’s covers. Instead, they got something that looked like a live-action film.

This change impacted how chainsaw man fan service was perceived. By making the world look real, the sexualized moments felt less like "anime tropes" and more like real-world interactions. This groundedness made Makima’s manipulation feel more sinister and Himeno’s advances feel more desperate.

It’s a far cry from Fire Force or Seven Deadly Sins, where fan service is a tonal break for comedy. In Chainsaw Man, the tone never breaks. The horniness is part of the tragedy.

Notable Departures from Shonen Norms

- No "Accidental" Perversions: Denji is honest about what he wants. He’s not a "closet pervert." This honesty removes the "tease" factor often found in the genre.

- Body Horror Integration: Most fan service scenes in the series transition directly into horrific violence.

- Consequences: Characters who lean into their desires usually pay a heavy price, either emotionally or physically.

Recontextualizing the "Hype"

If you’re looking for a series that provides traditional, guilt-free fan service, Chainsaw Man is going to disappoint you. It’s a story about a boy who was treated like a dog and thinks that "being a dog" for a beautiful woman is a step up.

The "fan service" is a mirror. It reflects Denji’s stunted growth and the audience’s own expectations of the medium. When we cheer for Denji to "get the girl," we’re often cheering for his own destruction without realizing it. Fujimoto is a master of making the reader feel like a co-conspirator in Denji’s misery.

👉 See also: Jack Blocker American Idol Journey: What Most People Get Wrong

Actionable Takeaways for Readers and Critics

Understanding the nuance of chainsaw man fan service requires looking past the surface level of the panels. If you're analyzing the series or just diving in for the first time, keep these perspectives in mind:

1. Watch the framing, not just the subject.

Notice how the camera (or panel) moves. Is it meant to make you feel empowered, or is it meant to make you feel as small and desperate as Denji? Usually, it's the latter.

2. Contextualize the desire.

Every time a character uses their sexuality, ask what they are trying to gain. In the world of Chainsaw Man, nothing is free, especially not intimacy.

3. Recognize the deconstruction.

Fujimoto is likely mocking the very tropes he is drawing. If a scene feels "too much" or "too typical," wait for the punchline—it’s usually a gut-punch of reality or a sudden shift into body horror.

4. Separate the anime from the manga.

The anime adds a layer of "prestige" realism that changes the "vibe" of the fan service. The manga is more frantic and punk-rock, making the same scenes feel more like a fever dream.

The real "service" Fujimoto provides isn't sexual—it's emotional. He gives us characters who are deeply, fundamentally broken and allows them to find small moments of peace in a world that wants to eat them alive. That’s much more satisfying than a panty shot.

To get the most out of Chainsaw Man, stop looking for the tropes you've seen in a hundred other series. Start looking for the subtext. When you realize that the "sexy" moments are actually the most dangerous parts of the story, the tension becomes unbearable. That’s where the true genius of the series lies. It’s not about what you see; it’s about how it makes you feel once the blood starts spraying.

Next Steps for Deepening Your Understanding:

Read the "Look Back" and "Goodbye, Eri" one-shots by the same author. They provide a massive amount of context for how Fujimoto views the human body, gaze, and the relationship between the creator and the audience. This will change how you view every single panel of Chainsaw Man.