You walk into a hole in a limestone cliff in the Dordogne, and suddenly, the 21st century just... evaporates. It's damp. It smells like wet earth and ancient calcium. Then you see it—a horse painted in ochre that looks like it’s breathing. Honestly, looking at caves in France prehistoric art isn't just a history lesson; it's a weirdly personal encounter with someone who lived 30,000 years ago but had the exact same creative itch you do.

Most people think these places are just "caveman doodles." That is a massive mistake.

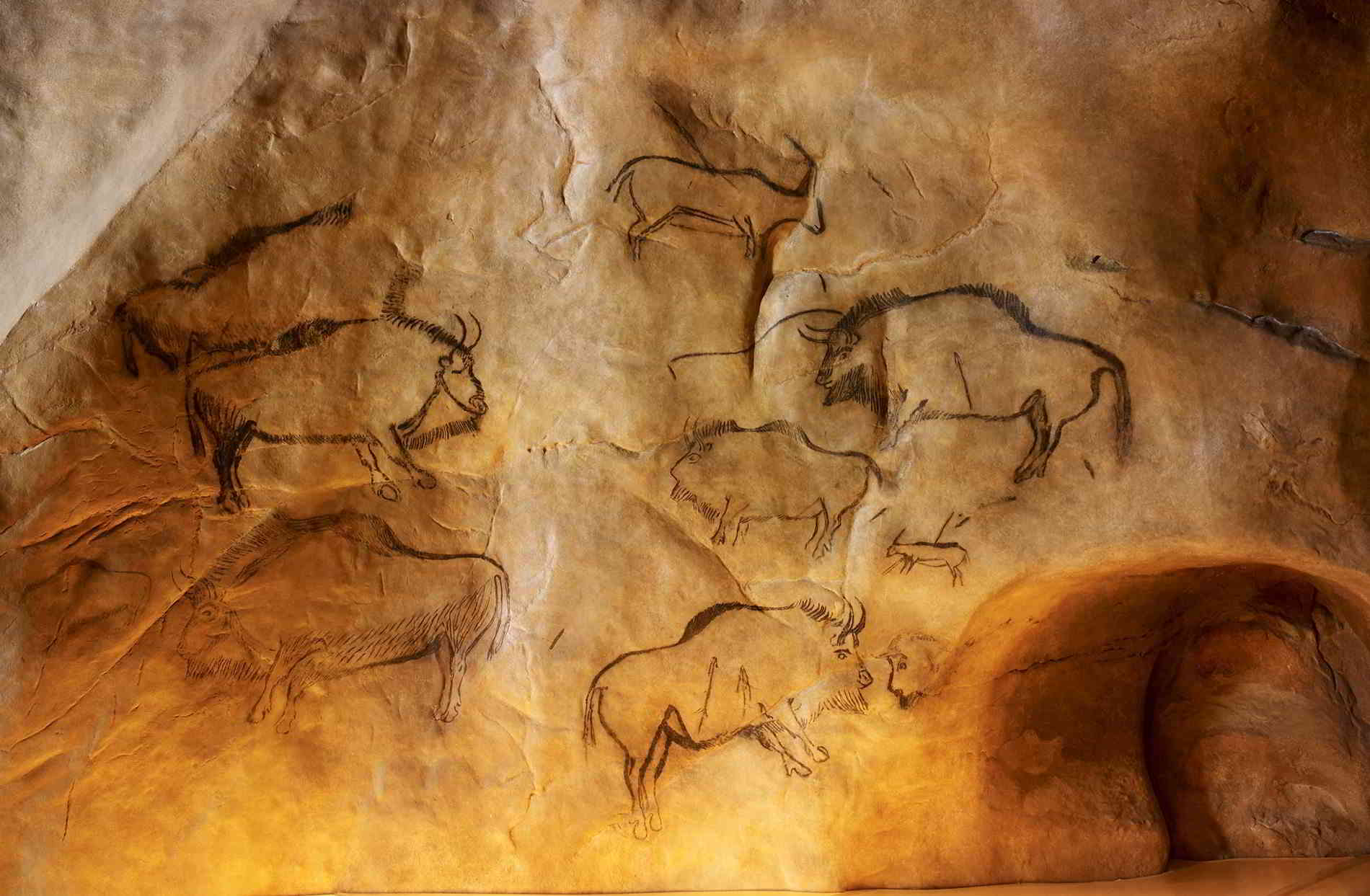

We’re talking about sophisticated galleries. These weren't homes; they were sanctuaries, cathedrals, or maybe even the world’s first cinemas. When you see the way a flickering torch makes a bison’s legs look like they’re galloping across a jagged rock face, you realize these artists weren't primitive. They were geniuses who knew exactly how to use the natural contours of the stone to create 3D effects.

The Lascaux Problem: What You Can Actually See

Lascaux is the big one. It’s the "Sistine Chapel of Prehistory." But here’s the kicker: you can’t actually go inside the real Lascaux.

Back in 1940, some teenagers and a dog named Robot found it. It was a miracle. But by the 1960s, the breath of thousands of tourists was literally rotting the paintings. Black mold and "green sickness" (algae) started eating the 17,000-year-old masterpieces. The French government shut it down fast.

Today, you visit Lascaux IV. It’s a "facsimile," which sounds like a fancy word for a fake, but it’s actually an engineering marvel. They used laser mapping to recreate every single bump and crack in the cave wall within millimeters. It’s cold, it’s dark, and it’s eerily silent. Even though you know it’s a recreation, the weight of the imagery—the Great Hall of the Bulls—still hits you in the gut.

The bulls are massive. Some are over 17 feet long. Why that big? Why there? Researchers like the late Norbert Aujoulat spent decades studying the "seasonality" of these paintings. He noticed that the animals are often depicted in specific stages of their life cycles—deer in autumn, horses in spring. It wasn't just random art; it was a calendar.

The Mystery of the "Negative" Handprints

One of the most haunting things you’ll see in caves in France prehistoric locations isn't the animals. It’s the hands.

📖 Related: The Gwen Luxury Hotel Chicago: What Most People Get Wrong About This Art Deco Icon

At Pech Merle, there are these "negative" handprints. Someone held their hand against the wall and blew pigment through a hollow bone or a reed, leaving a silhouette. You’re looking at the literal physical signature of a human being from 25,000 years ago.

There’s a weird detail most people miss: many of these hands have "missing" fingers. For years, archaeologists thought these people were constantly mutilating themselves or losing fingers to frostbite. But a lot of modern researchers, including those who study sign language and hunting signals, think they were just folding their fingers down to communicate specific codes. It was a language. A silent, permanent shout across time.

Chauvet: The Game Changer That No One Gets to Visit

If Lascaux is the famous middle child, Chauvet is the mysterious, older, much more talented sibling.

Discovered in 1994, Chauvet Cave changed everything we thought we knew about human evolution. The art there is roughly 36,000 years old. That is double the age of Lascaux. Before Chauvet, the prevailing theory was that art started simple and got better over thousands of years. Chauvet blew that out of the water.

The charcoal drawings of lions and rhinos there are stunningly realistic. They use perspective. They use shading. It proves that humans didn't "learn" to be artists over eons—we showed up on the scene already knowing how to capture the soul of an animal.

Since the cave is sealed tighter than a vacuum, you have to visit the Grotte de Chauvet 2 in the Ardèche region. It’s a massive project that cost about 55 million euros. Is it worth it? Yeah. Because seeing a panel of 16 lions chasing a herd of bison in a 36,000-year-old "action sequence" is something that stays with you.

Why the Ardèche is Different from the Dordogne

You’ve got two main "hubs" for these caves.

👉 See also: What Time in South Korea: Why the Peninsula Stays Nine Hours Ahead

- The Dordogne (Périgord): This is the classic. It’s lush, full of castles, and has the highest concentration of decorated caves like Font-de-Gaume and Les Combarelles.

- The Ardèche: Rougher, more dramatic landscapes. It’s home to Chauvet. It feels more "wild."

If you want the "authentic" experience where you actually see real, original pigment on a real cave wall, you have to go to Font-de-Gaume. They only let a tiny handful of people in per day to keep the CO2 levels low. You have to book months in advance. You’re standing in a narrow crevice, and the guide points a dim light at a reindeer, and you realize you’re breathing the same air that preserved that paint for 14,000 years. It’s terrifying and beautiful.

The Weird Science of Cave Music

Here’s something most people don't think about: what did these caves sound like?

A researcher named Iégor Reznikoff did something fascinating. He walked through these caves singing different notes to test the acoustics. He found a direct correlation between the "resonance points" of a cave and where the paintings were located.

Basically, if a certain part of the cave had a crazy echo, that’s where they painted the loudest animals, like bulls or mammoths. If a spot was quiet and muffled, you might find small, delicate drawings. These weren't just art galleries; they were likely locations for ritualistic chanting and music. Imagine the sound of a bone flute (they’ve found those, too) echoing off those walls while the shadows of the animals danced in the firelight. It was a full sensory experience.

Navigating the Practicalities (Because it’s a Mess)

You can't just show up and expect to see caves in France prehistoric wonders. You will be disappointed.

Most of these sites are managed by the Centre des Monuments Nationaux.

- Booking: For places like Font-de-Gaume, if you aren't online the second tickets go on sale, you're out of luck.

- Clothing: Even if it's 35°C outside in July, it’s a constant 13°C (about 55°F) inside. Bring a sweater. And wear shoes with grip. Mud and limestone are a slippery combo.

- Claustrophobia: Some of these "passages" are tight. If you don't like small spaces, stick to the large-scale facsimiles like Lascaux IV, which feel much more open.

The Misconception of the "Caveman"

We need to kill the "brute" stereotype. The people who made this art were us. They had the same brain capacity. They had needles to sew tailored clothing. They had jewelry made of shells and teeth.

✨ Don't miss: Where to Stay in Seoul: What Most People Get Wrong

When you look at the "Panel of the Spotted Horses" at Pech Merle, you see these tiny red dots and handprints around the horses. For a long time, scientists thought the spots were just "abstract art." Then, DNA testing on ancient horse bones proved that a specific breed of spotted horse actually existed back then. They weren't being "artsy"—they were being biological illustrators. They were observing their world with a level of detail that most of us, glued to our phones, have completely lost.

Deep Dive: Rouffignac and the "Cave of a Hundred Mammoths"

If you hate walking, Rouffignac is your place. You ride an electric train into the mountain.

It’s nicknamed the Cave of a Hundred Mammoths because, well, it has a lot of mammoths. But the coolest part is the "floor." You’ll see these deep circular depressions in the ground. Those are bear nests. Extinct Cave Bears used to hibernate here. You can actually see the claw marks on the walls where the bears scratched the stone, sometimes right next to (or under) the human paintings. It’s a reminder that humans weren't the only ones using these spaces. We were just the ones who decided to decorate them.

Actionable Steps for Your Prehistoric Pilgrimage

Don't just drive to Les Eyzies and hope for the best. Follow this path:

- Secure the "Real" Tickets First: Try for Font-de-Gaume or Rouffignac. These are the "real" ones. If you get these, build your trip around those dates.

- The Hub Base: Stay in Sarlat-la-Canéda or Les Eyzies. Les Eyzies is literally built into the cliffs and houses the National Museum of Prehistory. Go there before the caves to understand the tools you'll be seeing.

- The "Shadow" Sites: Don't ignore the Abri de Cap Blanc. It’s not a deep cave, but a rock shelter featuring incredible 3D sculptures (bas-reliefs) of horses. It’s one of the few places you can see prehistoric sculpture in its original spot.

- The Night Factor: If you can, visit a cave in the late afternoon when the crowds thin out. The silence of the Vézère Valley at dusk helps set the mood for what you've just seen.

- Respect the Rules: No photos. Seriously. The flash ruins the pigments, and the guides will (rightfully) kick you out. Just put the phone away and use your eyes. Your brain will remember it better anyway.

The biggest takeaway from visiting caves in France prehistoric sites? It’s the realization that we haven't actually "evolved" as much as we think. Our tech got better, sure. But the urge to stand in the dark, tell a story, and leave a mark that says "I was here" hasn't changed in 40,000 years.

Next Steps for Your Trip

- Check the Official Ticket Portals: Visit the Ticket-Monuments website exactly six months before your planned travel date to snag Font-de-Gaume spots.

- Download Offline Maps: Cell service in the valley walls of the Dordogne is notoriously spotty; you'll need GPS to find the smaller cave entrances.

- Read 'The Cave Painters' by Gregory Curtis: It provides the human backstories of the archaeologists who fought over these sites—it's more dramatic than a soap opera.