You’re standing in San Francisco, getting soaked. The sky is a flat, dismal grey, and you’re wondering why your phone says it’s "mostly cloudy" with a 0% chance of rain. You pull up the local california doppler weather radar map. It’s clear. There isn't a single green pixel in sight. It feels like a gaslighting session from the National Weather Service, but there's actually a very specific, very frustrating technological reason for this.

California’s geography is basically a radar technician’s nightmare. Between the massive Sierra Nevada range, the coastal hills, and the way our Pacific storms behave, "seeing" the rain isn't as simple as pointing a dish at the sky.

The "Beam Blockage" Problem

Radar works by sending out a pulse of energy. It hits something—a raindrop, a bird, a snowflake—and bounces back. Simple, right? Not when there’s a giant hunk of granite in the way.

In a flat state like Kansas, the radar beam can travel for miles without hitting anything but air. In California, we have the "Beam Blockage" issue. If you’re in a valley and the nearest Nexrad station is on the other side of a mountain range, that beam is hitting the mountain, not the storm behind it. This creates massive "blind spots" in places like the North Coast or deep within the Central Valley.

The beam also travels in a straight line, but the Earth is curved. By the time a radar pulse from the San Francisco Bay Area (the KUXR station on Mt. Umunhum) reaches the North Bay, the beam might be 10,000 feet in the air. If the rain is happening lower than that—which it often does in California—the radar literally shoots right over the top of the storm. You’re getting wet, but the radar thinks the sky is empty.

NEXRAD and the Dual-Pol Revolution

Most of what we see on a standard california doppler weather radar feed comes from the WSR-88D stations. These are the big "soccer ball" domes you see on hillsides. About a decade ago, these were upgraded to "Dual-Polarization."

Old radar only sent out horizontal pulses. It could tell you how much stuff was in the sky, but not what it was. Dual-pol sends out both horizontal and vertical pulses. This allows meteorologists to see the shape of the object. Is it a round raindrop? A flat, pancake-shaped melting snowflake? Or is it a "debris ball" from a wildfire or a rare California tornado?

This tech is why we can now tell the difference between heavy rain and "biologicals." If you’ve ever seen a weird, expanding circle on a radar map on a clear night, you’re likely seeing a massive "pulse" of birds or insects taking flight at once. The dual-pol data lets experts filter that out so you don't think a swarm of ladybugs is a thunderstorm.

The Atmospheric River Dilemma

California doesn't usually get the classic "popcorn" thunderstorms they see in the Midwest. We get Atmospheric Rivers (ARs). These are long, narrow bands of water vapor that carry more water than the Mississippi River.

The problem? ARs are often "warm rain" processes. They don't always have the big, icy tops that radar loves to bounce off of. When an AR hits the coastal ranges, the air is forced upward—a process called orographic lift. This creates intense, localized dumping of rain at low altitudes.

Because this happens so low to the ground, our primary california doppler weather radar network often underestimates the intensity. This is why agencies like Scripps Institution of Oceanography have started installing "gap-filler" radars. These are smaller, X-band units that sit lower to the ground and can see those shallow, high-intensity rain bands that the big Nexrad stations miss.

Why the "Delay" Happens

People get annoyed when they see rain out the window but the map says it's five miles away. Radar isn't a live video feed. It’s a scan.

The radar dish rotates 360 degrees, then tilts up slightly and rotates again. It does this multiple times to create a 3D "volume scan." Depending on the mode the radar is in—"Clear Air" vs. "Precipitation"—it might take 4 to 10 minutes to finish a full scan. By the time that image hits your app, it’s already "old" data.

In fast-moving storm cells, especially during a high-wind event in the Cajon Pass or over the Grapevine, a lot can change in seven minutes.

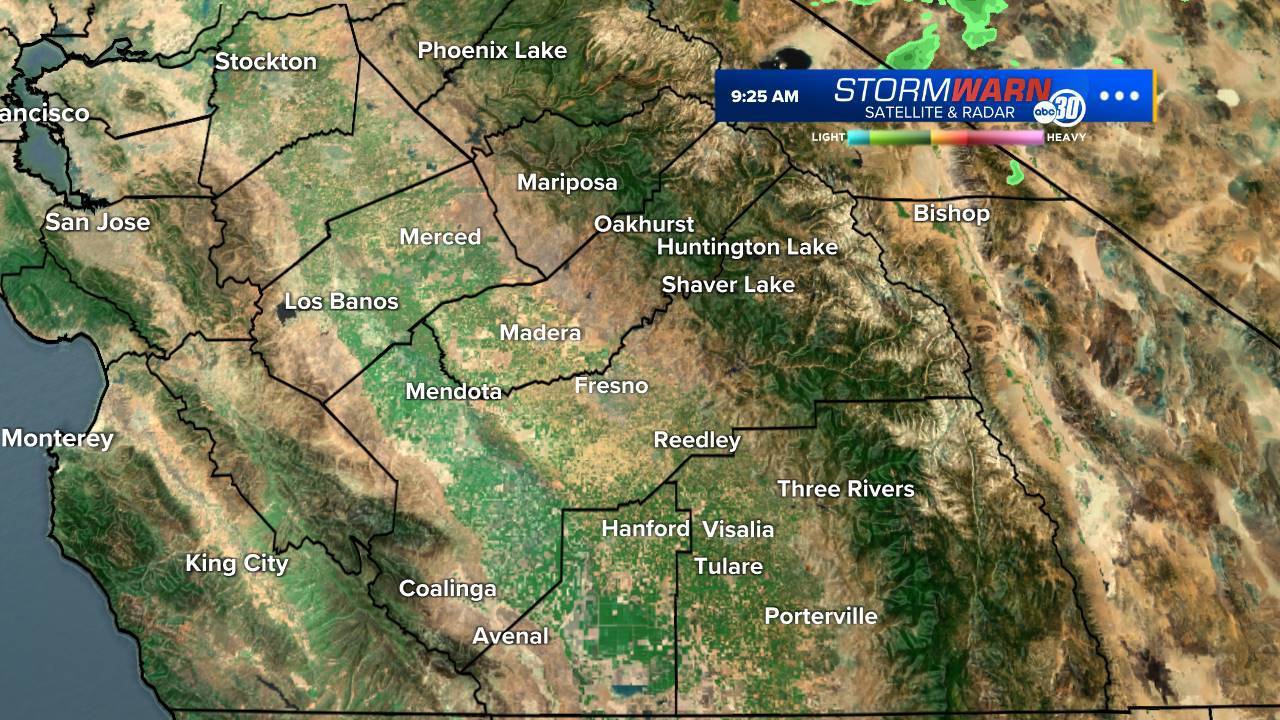

The Five Main Stations You Should Know

If you want to be a local weather nerd, you have to stop looking at "The Weather Channel" app and start looking at the raw station data. California is covered by several key Nexrad sites:

- KDAX: Located near Sacramento, covers the northern Central Valley.

- KUXR: South of San Jose, the "eye" for the Bay Area.

- KVTX: Near Los Angeles, crucial for seeing the moisture coming up from the bight.

- KNKX: San Diego’s main eye.

- KHNX: Near Hanford, covering the southern San Joaquin Valley.

Each of these has its own quirks. KUXR, for instance, has to deal with the "terrain shadow" of the Santa Cruz mountains. KVTX has to filter out the massive amounts of ground clutter caused by the urban sprawl of LA.

Wildfires and "Pyrocumulus"

One of the most intense uses of california doppler weather radar lately hasn't been for rain at all. It’s for fire. When a wildfire gets hot enough, it creates its own weather—a pyrocumulus cloud.

The radar can actually track the smoke plume. Meteorologists look for a "V-notch" in the plume, which indicates intense heat and upward motion. This is vital for fire crews because it tells them when the fire is about to "collapse." When a massive smoke column falls back to earth, it sends out a blast of wind in all directions that can trap firefighters. Radar is the only way to see that collapse happening in real-time.

How to Read the Map Like a Pro

Most people just look for the colors. Green is light, yellow is medium, red is heavy. But that’s barely scratching the surface.

If you see "Velocity" data, you're looking at the Doppler effect. Red means air moving away from the radar; green means air moving toward it. If you see bright red right next to bright green, that’s "couplet" or rotation. That’s where a tornado or a waterspout is likely forming. In California, we see this most often in the Central Valley during spring "cold core" setups.

Also, look for "Correlation Coefficient" (CC). This is a metric of how "similar" the objects in the air are. If the CC is high (near 1.0), it’s all rain. If it drops suddenly, the radar is seeing "mixed bag" stuff—maybe hail, or maybe it’s picking up shingles from a roof that just got blown off.

Actionable Steps for the Next Big Storm

Next time a "Pineapple Express" is forecast for the coast, don't just trust the big-name apps. They often smooth out the data, making it look prettier but less accurate.

📖 Related: How to Set Up a Subwoofer Without Making Your Room Sound Like a Muddy Mess

- Use the "Gap Fillers": If you are in the Bay Area, look for the "AQPI" (Advanced Quantitative Precipitation Information) radar network. These are the small, local radars that see the low-level rain the big guys miss.

- Check the Base Reflectivity: If you want to see exactly where it's raining right now, look at the "0.5 degree" tilt. This is the lowest scan possible. Anything higher is looking at clouds, not what’s hitting the pavement.

- Verify with M-PING: Download the "mPING" app (from NOAA). It lets you report what’s actually falling at your house. Meteorologists use these crowdsourced reports to "ground truth" their radar data. If the radar says rain but you see hail, tell them. It helps the algorithm learn.

- Watch the Composite: "Base" radar shows one station. "Composite" merges them all together. If you want to see the whole state's movement, use composite. If you want to see if a flood is coming to your specific street, stick to the local base station.

California's weather is governed by some of the most complex terrain on Earth. Our radar network is a masterpiece of engineering, but it isn't magic. Understanding that the mountains are literally hiding the rain from the "eye" of the radar is the first step toward not getting caught without an umbrella._