Tap dancing used to be polite. It was Fred Astaire in a tuxedo, smiling through a cinematic dream, or maybe a flashy chorus line on a Broadway stage where every click was synchronized to perfection. Then came 1995. Specifically, then came George C. Wolfe and a young, dreadlocked virtuoso named Savion Glover. When Bring in 'da Noise, Bring in 'da Funk hit the Public Theater before moving to the Ambassador Theatre on Broadway, it didn't just change the genre. It broke the floorboards.

Most people think of tap as just rhythm. It’s more than that. It’s history. Honestly, if you haven't seen the archival footage of Glover hitting the floor with a heavy, heel-driven intensity that looks more like a construction site than a dance studio, you’re missing the point of what happened in the mid-nineties. This show wasn't just a "musical." It was a rhythmic history of the African American experience, told through the soles of feet. It was loud. It was aggressive. It was, quite literally, noise and funk.

The Rhythm of History: What People Get Wrong

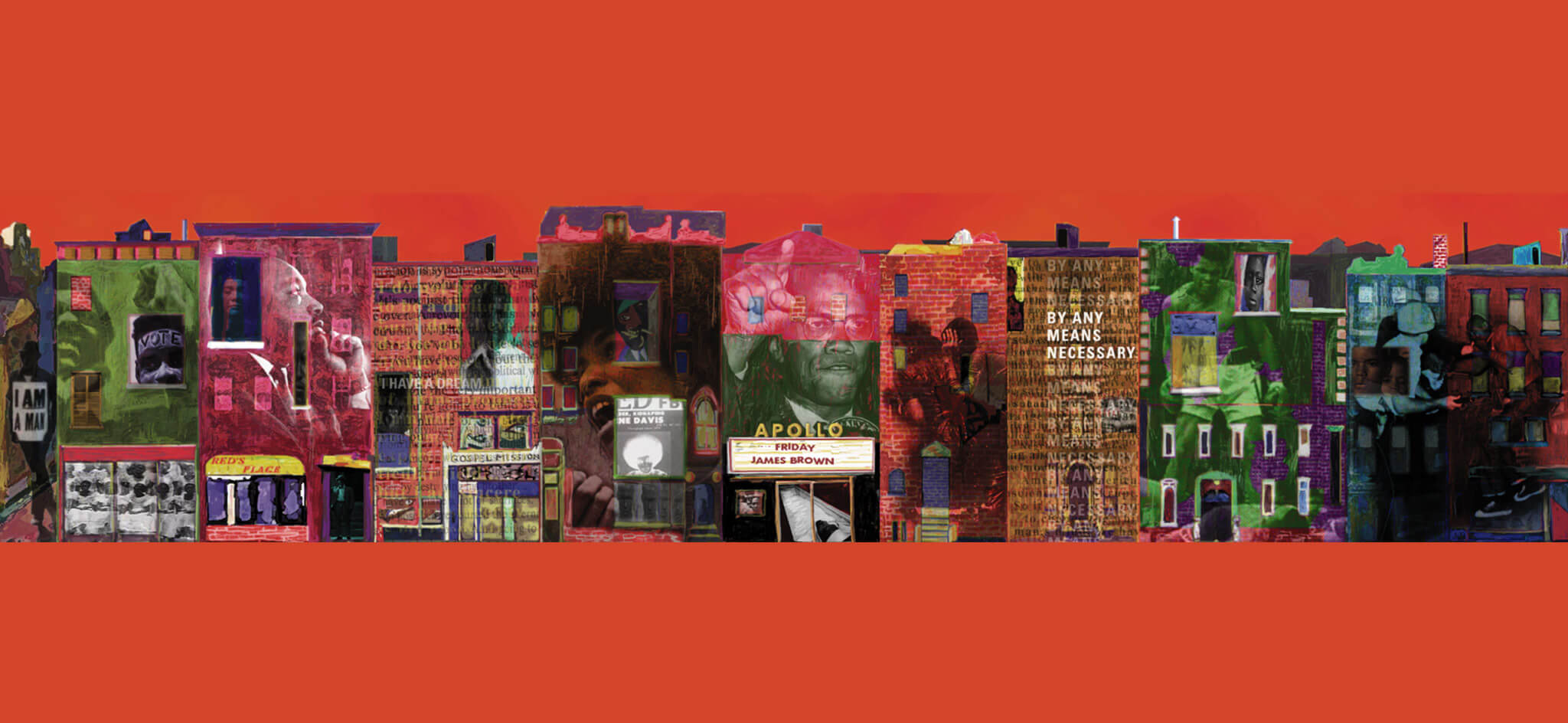

There’s this weird misconception that Bring in 'da Noise, Bring in 'da Funk was just a showcase for Savion Glover’s talent. While he was the undisputed star and the person who won the Tony for Best Choreography, the show was a collaborative explosion. George C. Wolfe, who directed it, wanted to tell a story that spanned from the slave ships to the modern streets of New York City.

They used "the beat" as a character.

Think about the section titled "The Slave Ships." There are no upbeat tunes here. Instead, you have the heavy, industrial sound of chains and wood. The tap isn't light or airy; it’s a form of communication and a form of survival. The show dismantled the "Happy Feet" stereotype that had plagued black tap dancers for decades during the vaudeville era. It took the art form back from the polished Hollywood version and gave it its grit back.

The Industrial Soundscape

One of the most iconic parts of the show involved the use of pots, pans, and five-gallon plastic buckets. This wasn't some gimmick. It reflected the "rhythm tap" style found on the streets of NYC. It was about making music with whatever was available. When the performers started hitting those buckets, the sound didn't just fill the room—it rattled your teeth. This was the "Noise" part of the title. It was unapologetic.

✨ Don't miss: Why October London Make Me Wanna Is the Soul Revival We Actually Needed

Why the 1996 Tony Awards Changed Everything

If you look back at the 1996 Tony Awards, the vibe was electric. Bring in 'da Noise, Bring in 'da Funk was nominated for nine awards. It took home four. But the wins weren't the real story. The real story was the performance. Seeing Savion Glover and the company perform on that telecast was a "where were you" moment for the theater community.

It felt dangerous.

Broadway is usually very "safe." This felt like a riot in the best way possible. It proved that you didn't need a traditional "book" musical structure—with a clear protagonist, love interest, and a happy ending—to move an audience. You just needed truth and a hell of a lot of rhythm. Jeffrey Wright, who later became a massive star, was part of the original cast, narrating the journey. The layers of talent were just insane.

The "Dressing Room" and the Critique of Hollywood

There is a specific scene in the show that many people forget, but it's perhaps the most biting. It deals with the way black dancers were treated in early Hollywood. The dancers are forced to grin and perform a "Uncle Tom" style of dance to please white audiences.

The contrast between that forced, fake smile and the raw, angry, powerful tapping they do when they are "themselves" is heartbreaking. It’s a critique of the industry that was hosting them. It’s meta. It’s brilliant. Honestly, it’s the kind of social commentary we see a lot now, but in 1995? It was revolutionary.

🔗 Read more: How to Watch The Wolf and the Lion Without Getting Lost in the Wild

The Technical Brilliance of Savion Glover

Savion Glover is often called a "living legend," but that feels too static. Watching him dance in Bring in 'da Noise, Bring in 'da Funk was like watching a jazz musician improvise, but with his heels. He didn't just tap; he "hit." That’s the term they use: "hitting."

It’s a style called power tap.

$F = ma$. Force equals mass times acceleration. Glover understood this physics instinctively. He would lean his weight forward, stay low to the ground—unlike the upright, balletic style of traditional Broadway tap—and use the floor as a drum head. He wasn't dancing on the floor; he was playing the floor.

The Feet as an Instrument

If you listen to the original cast recording—yes, a tap show has a cast recording—you realize how complex the compositions are. Ann Duquesnay, who won a Tony for her performance, provided the vocals that acted as the melodic backbone, but the feet were the percussion section. They weren't just hitting 4/4 time. They were doing complex polyrhythms that you’d usually only hear in high-level Afro-Cuban jazz.

The Legacy: What Happened After the Noise?

The show ran for 1,135 performances. That’s a massive run for something so experimental. But its real legacy isn't in the box office numbers. It's in the way it paved the way for shows like Hamilton or Shuffle Along (2016). It broke the mold of what a "Black Show" on Broadway could be. It didn't have to be a revival of a 1920s jazz hit; it could be contemporary, political, and loud.

💡 You might also like: Is Lincoln Lawyer Coming Back? Mickey Haller's Next Move Explained

It also changed how tap was taught. After Bring in 'da Noise, Bring in 'da Funk, every kid in a dance studio wanted to learn "rhythm tap." The demand for heavy-soled, professional-grade tap shoes skyrocketed. People stopped wanting to look like Shirley Temple; they wanted to look like Savion.

Where to Find the Funk Today

Unfortunately, there isn't a high-definition, multi-cam pro-shot of the entire original production available on streaming services. It’s one of the great tragedies of musical theater history. However, you can find bits and pieces.

- The Lincoln Center Library for the Performing Arts: They have the archival tape, but you usually have to have a professional or academic reason to view it.

- The 1996 Tony Awards Performance: Available on YouTube and still holds up as one of the best five minutes in television history.

- "The Tap Dance Kid": If you want to see where Savion started, look up his early work, but realize that Noise/Funk was his evolution into a master.

How to Appreciate the Art Form Now

If you want to actually understand the impact of Bring in 'da Noise, Bring in 'da Funk, don't just read about it. You have to feel it. Tap is a physical medium.

First, go back and listen to the track "The Beat." It’s the opening of the show. Listen to how the rhythm starts with a single person and builds into a wall of sound. Notice the lack of orchestral instruments at first. It’s just human effort.

Second, understand that this show was a reaction to the "Disneyfication" of Broadway. In the mid-90s, The Lion King and Beauty and the Beast were starting to dominate. Noise/Funk was the antithesis of that. It was sparse, dark, and focused on the human body rather than massive puppets or stage magic.

Actionable Insights for Theater Fans and Dancers

- Study the "Hoofer" Tradition: Look up Jimmy Slyde, Chuck Green, and Bunny Briggs. These were the men who taught Savion. You can't understand Noise/Funk without understanding the lineage of the "hoofers" who kept the art alive when it wasn't fashionable.

- Listen for the "Heel": In traditional tap, the toe is the star. In Bring in 'da Noise, Bring in 'da Funk, the heel provides the bass. Train your ears to hear the low-end frequencies in the dance.

- Analyze the Narrative Structure: If you’re a writer or creator, look at how George C. Wolfe used vignettes instead of a linear plot. It’s a masterclass in thematic storytelling.

- Support Modern Tap: The "Noise/Funk" era led to companies like Dorrance Dance. Support contemporary tap dancers who are still pushing the boundaries of what the floor can do.

The show eventually closed in 1999, but its "noise" hasn't really stopped. It’s in every street performer hitting a bucket in Times Square. It’s in every Broadway show that dares to be a little too loud and a little too honest. It taught us that as long as you have a rhythm, you have a voice.

Basically, the show was a reminder that history isn't just something you read in a book. Sometimes, it’s something you stomp out on a wooden stage until the whole building shakes. That’s the funk. That’s the noise. And that’s why we’re still talking about it thirty years later.