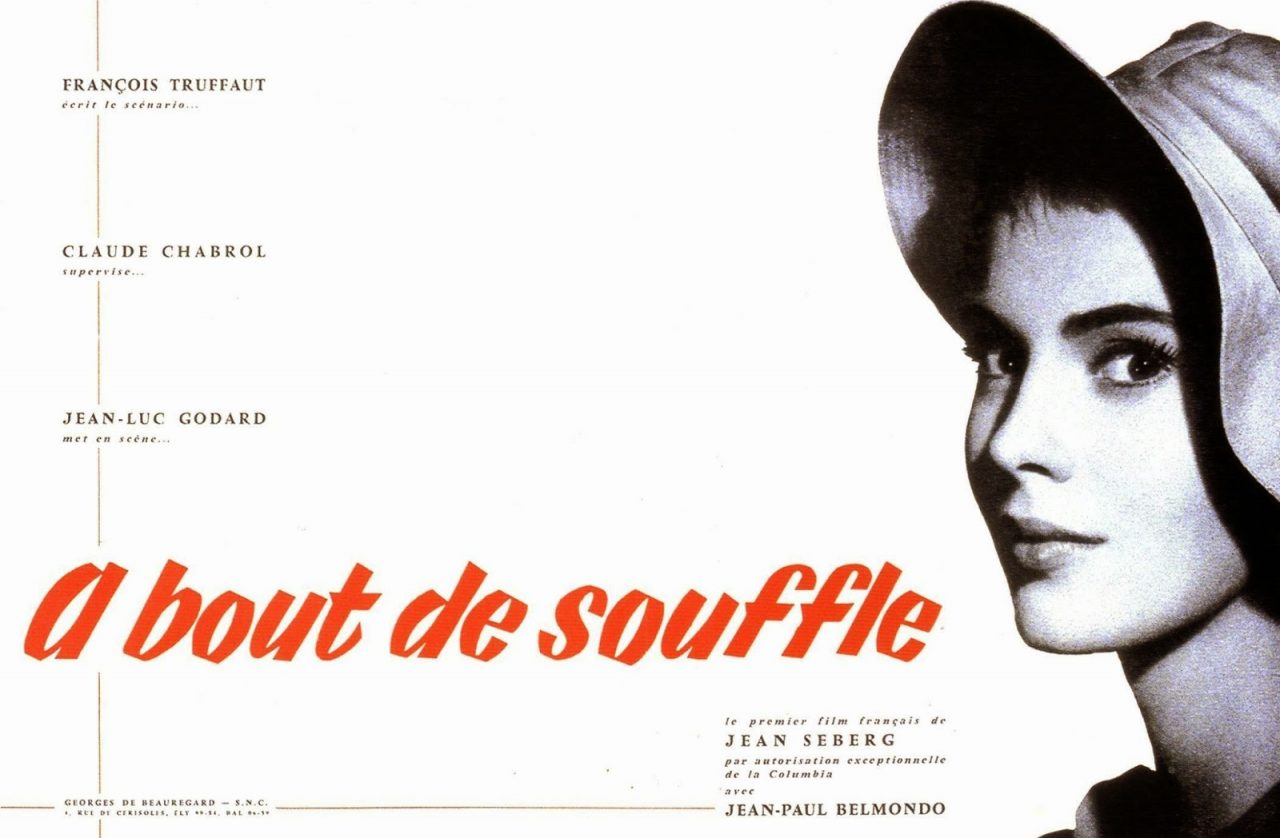

Jean-Luc Godard didn't just make a movie in 1960. He threw a grenade. When Breathless (originally titled À bout de souffle) hit French theaters, it didn't just "influence" cinema; it basically broke the existing rules of how stories are told on screen. Think about the movies you watch today. Every time a director uses a jump cut to show a character’s frantic energy or lets an actor look directly into the lens to break the fourth wall, they’re paying rent to a house Godard built over sixty years ago.

It’s weird.

People talk about "classic cinema" and usually picture sweeping orchestras or stiff acting. Breathless is the opposite. It’s messy. It’s loud. It feels like it was filmed by a guy who just discovered a camera and decided to see what happened if he ignored every textbook in the industry. Honestly, that's exactly what happened.

The Chaos Behind the Camera

You’ve gotta understand the vibe of Paris in the late 1950s. The "Tradition of Quality" was the standard—big, expensive, studio-bound literary adaptations. Godard and his buddies at the Cahiers du Cinéma magazine hated it. They wanted something real. Something that felt like the jazz music they were obsessed with.

The production of Breathless was a total disaster by any normal standard. There was no finished script. Seriously. Godard would wake up, scribble some lines in a notebook at a cafe, and hand them to Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg right before the cameras rolled. Raoul Coutard, the cinematographer, had to push a wheelchair around to get tracking shots because they couldn't afford professional dollies.

It was guerrilla filmmaking before that was even a term.

They filmed without permits. They hid cameras in mail carts to film people on the Champs-Élysées without them knowing. When the first cut of the film came out too long, instead of cutting out whole scenes, Godard just snipped frames out of the middle of shots. This birthed the "jump cut." It wasn't some high-concept artistic choice at first; it was a practical solution to a length problem that accidentally changed the visual language of the 20th century.

✨ Don't miss: Chase From Paw Patrol: Why This German Shepherd Is Actually a Big Deal

Jean-Paul Belmondo and the Birth of Cool

Before this movie, leading men were polished. They were Gary Cooper or Cary Grant. Then comes Belmondo as Michel Poiccard. He’s a thug. He’s a car thief. He’s obsessed with Humphrey Bogart to a point that is almost embarrassing. He rubs his lip with his thumb, stares at movie posters, and smokes constantly.

He’s not a "hero." He’s a jerk, honestly. But he’s magnetic.

The chemistry between him and Jean Seberg, who plays Patricia, is what keeps the movie from drifting off into pure experimentation. Seberg was an American actress who had been chewed up and spit out by the Hollywood system after some flops. In Breathless, she’s iconic. The short hair, the "New York Herald Tribune" t-shirt—she became the face of the French New Wave.

Their conversations aren't like movie dialogue. They talk about nothing. They argue about whether they like each other. They spend twenty minutes in a bedroom just hanging out, smoking, and listening to records while Michel tries to convince her to run away to Italy with him. It feels like a vlog from 2026, not a movie from 1960.

Breaking the Rules of Narrative

Most movies follow a predictable arc. Problem, rising action, climax, resolution. Breathless doesn't care. Michel kills a cop in the first few minutes, but the movie isn't really a police procedural. It’s a character study of a guy who thinks he’s in a movie.

The editing is what really grabs you. In one famous scene, Michel is driving and talking to the audience. He turns to the camera and says, "If you don't like the sea, if you don't like the mountains, if you don't like the city... then get stuffed!"

🔗 Read more: Charlize Theron Sweet November: Why This Panned Rom-Com Became a Cult Favorite

It was a middle finger to the audience.

It told the viewer: "Hey, you're watching a movie. This isn't real. Wake up." This self-awareness is everywhere now, from Deadpool to Fleabag, but in 1960, it was revolutionary. It removed the "invisible wall" that cinema had spent decades trying to perfect.

Why We Still Watch It

Is it a "perfect" movie? No. It’s flawed. Some of the pacing is wonky, and if you aren't in the mood for existential rambling, you might find Michel annoying. But that’s the point. Godard wasn't looking for perfection; he was looking for truth.

The film captures a specific kind of youthful arrogance. That feeling that you’re the protagonist of a very cool, very tragic story, and that the world owes you something. It’s a movie about the idea of movies.

If you watch it today, you'll see things that feel clichés. But you have to remember: Breathless invented the clichés. It turned the handheld camera into a tool for intimacy rather than just news reporting. It proved that you didn't need a million dollars and a soundstage to make something that people would talk about for a century.

Impact on New Hollywood

Without this film, we don't get the American film revolution of the 70s. No Bonnie and Clyde. No Taxi Driver. Martin Scorsese and Quentin Tarantino have spent their entire careers referencing Godard’s work. Tarantino even named his production company, A Band Apart, after Godard’s film Bande à part.

💡 You might also like: Charlie Charlie Are You Here: Why the Viral Demon Myth Still Creeps Us Out

The DNA of the French New Wave is baked into every indie film made in a garage today. It gave filmmakers permission to be spontaneous. It said that style is substance.

How to Watch Breathless Like a Pro

If you’re going to dive into it for the first time, don't look for a tight plot. Look for the energy. Listen to the way the jump cuts mimic the rhythm of heartbeats or the frantic pace of a city.

Notice the lighting. It’s all natural. They used fast film stock meant for photojournalism so they wouldn't need big, bulky lights. This gives the whole movie a gritty, "you are there" feeling that studio films couldn't replicate.

Things to look for:

- The way Michel constantly imitates Humphrey Bogart.

- The lack of traditional "establishing shots" (Godard just throws you into the middle of the action).

- The ending. It’s famous for a reason, and it’s one of the most debated final lines in cinema history.

Basically, the movie is a vibe check.

It asks if you can handle a story that doesn't hold your hand. It’s about the freedom of being "breathless"—running so fast toward your own destruction that you don't have time to stop and think.

Actionable Takeaways for Film Lovers

If you want to truly appreciate the legacy of Breathless, don't just read about it. Experience the ripples it left behind.

- Watch it back-to-back with a 1950s Hollywood Noir. See the difference? The older film will feel like a play; Breathless will feel like a street fight.

- Experiment with the "Jump Cut." If you make videos, try cutting out the "boring" parts of a single shot where a person is moving from point A to point B. See how it adds urgency.

- Research the "Cahiers du Cinéma" group. Understanding that Godard, Truffaut, and Chabrol started as critics helps explain why they were so hell-bent on breaking the rules they had spent years analyzing.

- Visit a local repertory theater. This film was made for the big screen. The grain of the film and the scale of Paris are lost on a phone screen. If a local cinema is doing a "French New Wave" night, go.

The reality is that cinema is divided into two eras: before Breathless and after it. It’s the moment movies grew up and realized they could be whatever they wanted to be. It’s messy, it’s arrogant, and it’s absolutely essential. If you haven't seen it, you're missing the blueprint for modern storytelling. Get on it.