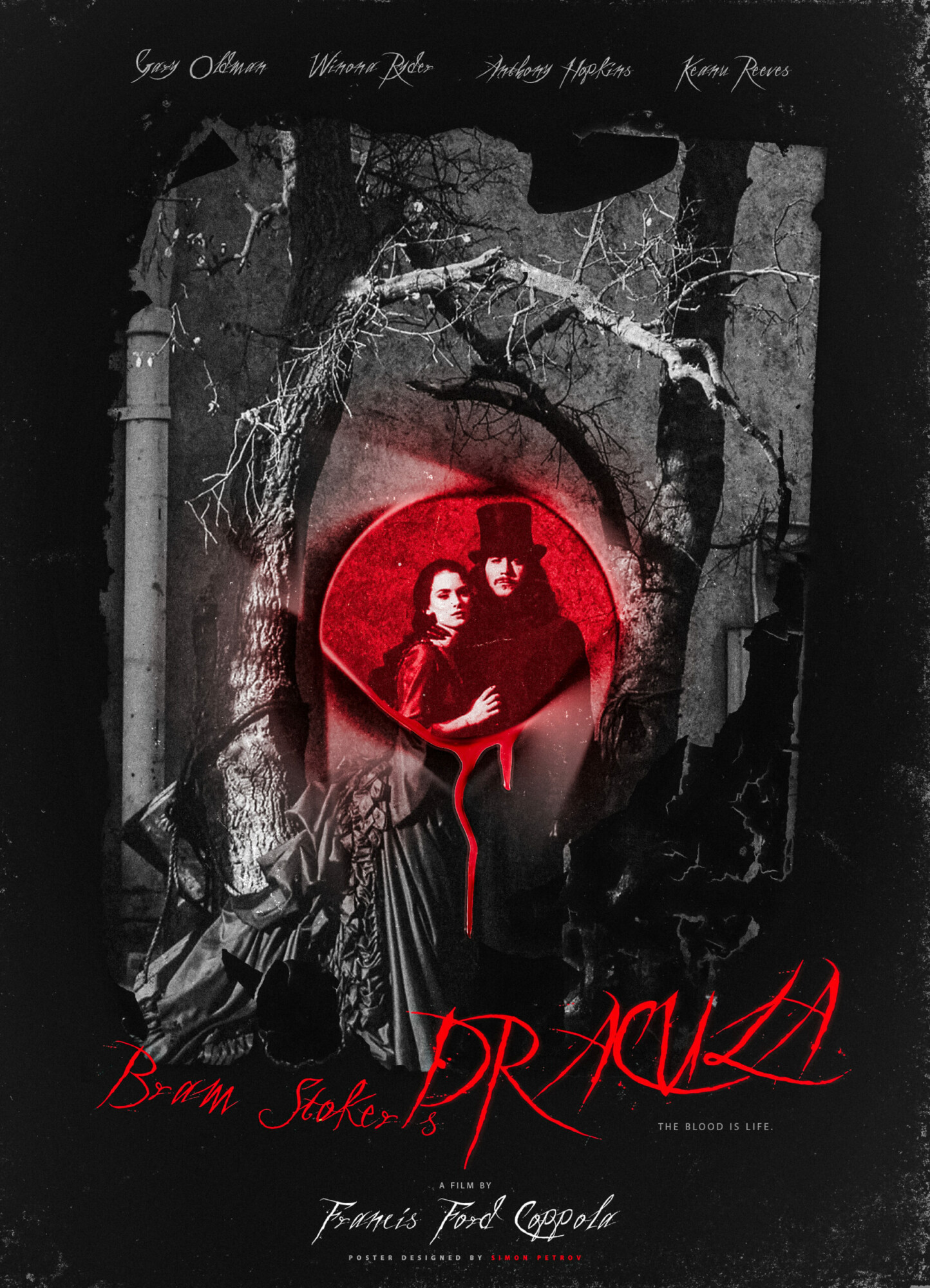

Francis Ford Coppola was kind of a madman for trying it. By the early nineties, Hollywood was already starting to flirt heavily with digital effects, but Coppola went the other way. He fired his initial effects team because they told him he couldn't do the movie without computers. He hired his son, Roman Coppola, instead. They decided to do everything "in-camera." It was a massive gamble. Honestly, that’s why Bram Stoker's Dracula 1992 remains such a visually arresting fever dream even thirty-plus years later. It doesn't look like a movie; it looks like a moving painting from the late 19th century.

Most people forget that this film wasn't just another vampire flick. It was a massive correction. Before 1992, the image of Dracula was stuck. You had the cape-swishing charm of Bela Lugosi or the sheer animalistic ferocity of Christopher Lee. Coppola wanted to go back to the source material—sorta. He kept the diary-entry structure of the 1897 novel but injected a heavy dose of tragic romance that wasn't actually in the book. It’s a weird mix of hyper-accurate Victorian detail and total operatic fantasy.

The Practical Magic of 1992

The "low-tech" approach is exactly what makes the film feel so grounded and eerie. If you watch the scene where Gary Oldman’s shadow moves independently of his body, you aren't looking at a digital layer. They used a "shadow puppet" technique on a backlit screen. It’s simple. It’s effective. It’s unsettling.

Gary Oldman was famously difficult on set, but his performance is arguably the most versatile version of the Count ever put to film. He goes from a wizened, ancient warlord with a "double-butt" hairstyle—as fans affectionately call it—to a dapper young prince in London. The sheer amount of makeup he endured was grueling. Greg Cannom, the makeup artist, won an Oscar for a reason. He created several distinct stages of Dracula's physical decay and rejuvenation.

Everything you see on screen was done using forced perspective, double exposures, and matte paintings. When the train crawls across a map of Transylvania, it’s not a digital overlay. It’s a physical model with a projection. This creates a specific "shimmer" to the image that CGI just cannot replicate. Digital effects often feel "too clean." Coppola’s film feels tactile and dirty. It feels like you could reach out and touch the velvet of the costumes.

Those Outrageous Costumes

Speaking of velvet, we have to talk about Eiko Ishioka. She had never designed costumes for a film before this. Coppola told her the costumes would be the "set." He stripped back the physical backgrounds and let the fabric do the storytelling. This is why Dracula wears a massive, flowing red robe that looks like a bloodstain across the floor.

It’s high art.

👉 See also: The Real Story Behind I Can Do Bad All by Myself: From Stage to Screen

The costumes were so heavy and intricate that the actors often struggled to move. Sadie Frost, who played Lucy Westenra, wore a burial dress inspired by a frilled lizard. It was bizarre. It was beautiful. It was completely unlike anything seen in horror movies at the time, which were mostly leaning into the "slasher" aesthetic of the eighties.

The Keanu Reeves Problem (Let’s Be Real)

We can’t talk about Bram Stoker's Dracula 1992 without addressing the British accent in the room. Keanu Reeves is a legend. He is a gift to cinema. But as Jonathan Harker? He was, quite frankly, out of his depth.

Keanu has admitted since then that he was exhausted when he took the role. He had just finished several other projects and his heart wasn't in the research. Against heavyweights like Anthony Hopkins and Gary Oldman, his flat delivery becomes almost comedic. Hopkins, playing Van Helsing, is chewing the scenery so hard he’s practically eating the props. Then you have Keanu, sounding like he’s trying to remember if he left the stove on back in Malibu.

It’s a flaw, sure. But in a weird way, it adds to the dreamlike, disjointed quality of the movie. Everything is so heightened and "extra" that having one character who feels completely out of place almost works for the fish-out-of-water narrative of Harker being trapped in a castle.

Why the Gore Still Hits Different

There’s a scene where Lucy is decapitated in her tomb. It’s messy. It’s brutal. Because they used practical blood rigs and physical prosthetics, the weight of the scene is heavy. In modern horror, blood often looks like digital ink—it disappears too quickly or doesn't interact with the light correctly.

In 1992, the blood was thick, corn-syrup-based, and got everywhere.

✨ Don't miss: Love Island UK Who Is Still Together: The Reality of Romance After the Villa

Coppola used a lot of "incamera" tricks like rewinding the film and double-exposing it to get the green mist scenes. This was old-school magic from the silent film era. He was essentially using the same techniques George Méliès used in the early 1900s. By using the technology of the era the book was written in, Coppola bridged the gap between the story’s origins and modern cinema.

The Legacy of the "New" Dracula

Before this movie, Dracula wasn't really a romantic lead. He was a monster. Coppola and screenwriter James V. Hart turned him into a fallen angel searching for his lost love, Elisabeta. This changed everything. It paved the way for Interview with the Vampire a few years later and, eventually, the entire "sexy vampire" trope that dominated the 2000s.

Without the 1992 film, you don't get the same DNA in shows like True Blood or The Vampire Diaries. It humanized the Count. It made him a victim of time and God, rather than just a nocturnal predator.

Technical Mastery Over Convenience

The production was a nightmare behind the scenes. Coppola was known for his "interactive" directing style, which often meant shouting and creating a chaotic environment to get real reactions from his actors. Winona Ryder and Coppola famously clashed during the filming of some of the more intense scenes.

Despite the friction, the result is a masterpiece of art direction. The film won three Academy Awards:

- Best Costume Design

- Best Sound Editing

- Best Makeup

It’s one of the few horror movies that the Academy actually took seriously. Usually, horror is relegated to the "technical" categories, but the sheer craft here was undeniable.

🔗 Read more: Gwendoline Butler Dead in a Row: Why This 1957 Mystery Still Packs a Punch

Real World Takeaways for Cinephiles

If you're looking to revisit Bram Stoker's Dracula 1992 or study it for the first time, keep an eye on the transitions. The way a character's eye dissolves into a tunnel or a peacock feather turns into a landscape is textbook editing.

To truly appreciate what Coppola achieved, you should:

- Watch the 4K Restoration: The color grading on the newer releases finally does justice to the saturation of the reds and golds that Ishioka intended.

- Compare it to the 1931 original: Notice how Coppola borrows the "crawling up the wall" shot but executes it with much more physical menace.

- Listen to the score: Wojciech Kilar’s soundtrack is arguably one of the best in horror history. It’s heavy, choral, and terrifying.

The film serves as a reminder that "limitations" are often the mother of invention. By refusing to use the easy digital tools of the time, Coppola created something timeless. It’s a messy, loud, over-acted, and stunningly beautiful piece of gothic art that will likely never be replicated in the age of green screens and AI-assisted rendering.

Go back and watch the scene where the three vampire brides emerge from the bedsheets. It’s a masterclass in slow-motion photography and practical layering. There is no computer intervention there—just clever lighting, a hole in the mattress, and a lot of silk. That’s the magic of 1992. It’s real. It’s there. You can feel it.

For anyone interested in the technical side of filmmaking, looking up the "behind the scenes" documentaries for this specific production is a must. It’s a crash course in how to trick the human eye using nothing but glass, mirrors, and light.