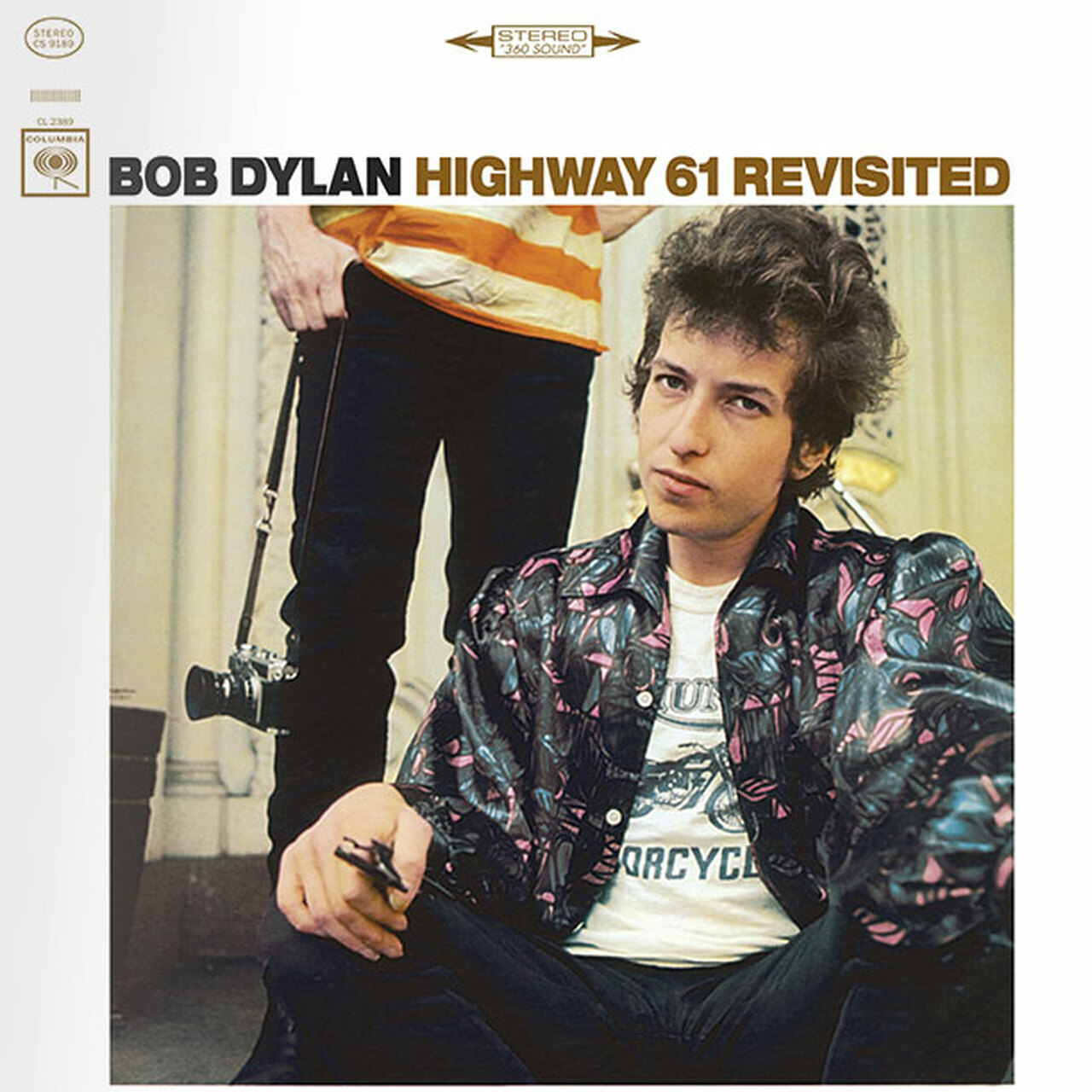

It starts with a crack. That snare hit at the beginning of "Like a Rolling Stone" wasn't just a drummer hitting a piece of kit; it was a guillotine dropping on the folk revival. When the Bob Dylan Highway 61 Revisited LP hit the shelves in August 1965, it didn't just change rock and roll. It basically invented the idea that a pop song could be a sprawling, surrealist nightmare.

You’ve probably heard the stories about Newport. People booing. Dylan in the leather jacket. Pete Seeger supposedly looking for an axe to cut the power cables. But the actual record is where the real revolution was happening. It’s messy. It’s loud. It sounds like it’s being recorded in a garage that’s slowly catching fire.

Honestly, it shouldn't work. The piano is out of tune in spots. Mike Bloomfield’s guitar pierces your ears. Dylan’s voice sounds like it’s been dragged through gravel and soaked in red wine. Yet, sixty years later, we’re still trying to figure out how he pulled it off.

The Highway That Rewrote the Rules

Most people think of highways as a way to get from A to B. For Dylan, Highway 61 was a literal road—it ran from his childhood home in Minnesota down to the Mississippi Delta, the birthplace of the blues. But on this album, the highway is more like a fever dream.

You’ve got God and Abraham arguing on the shoulder of the road. You’ve got the Georgia Sam he was a-goin' to the welfare line. It’s a carnival of the grotesque. Before the Bob Dylan Highway 61 Revisited LP, lyrics in popular music were mostly about holding hands or "I love you, yeah, yeah, yeah." Suddenly, Dylan is talking about "the ghost of electricity howling in the bones of her face."

What does that even mean?

It doesn't matter. You feel it. That’s the trick Dylan played on everyone. He moved music from the literal to the literary. He took the beatnik poetry of Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg and shoved it into a Fender Twin Reverb amp.

📖 Related: Howie Mandel Cupcake Picture: What Really Happened With That Viral Post

The Sound of a Nervous Breakdown

Let’s talk about the band. This wasn’t a group of polished session pros playing it safe. Dylan brought in Al Kooper, who famously sneaked onto the organ during the "Like a Rolling Stone" sessions even though he wasn't really an organ player.

Kooper was a guitar player. He was intimidated by Mike Bloomfield’s blistering blues licks, so he sat down at the Hammond B3. He was playing a split second behind the beat because he was trying to figure out the chord changes as they happened. That hesitation? That’s the "hook." It gives the song this weird, rolling, gospel-infused momentum that feels totally human and slightly unstable.

The production by Bob Johnston was a radical departure from the clean, compressed sound of the era. Johnston basically let the tapes roll. If a mistake sounded cool, it stayed. This gave the Bob Dylan Highway 61 Revisited LP a raw, "live" energy that made everything else on the radio sound like a toy.

"Desolation Row" and the Death of the Three-Minute Single

The album ends with "Desolation Row." It’s eleven minutes long. In 1965, that was insane. Radio stations didn't know what to do with it. It’s just an acoustic guitar, a flickering bass line, and Charlie McCoy’s Spanish-style guitar fills dancing around Dylan’s voice.

It’s a parade of historical and fictional characters: Einstein disguised as Robin Hood, Casanova being punished, the Titanic. It feels like the end of the world. By the time the needle hits the run-out groove, you feel exhausted.

Critics like Greil Marcus have spent decades dissecting these lyrics. Was Dylan talking about the Civil Rights movement? The Cold War? His own fame? Probably all of it. Or maybe none of it. Dylan has always been a shapeshifter. He’s the guy who said, "I just write 'em, I don't explain 'em."

👉 See also: Austin & Ally Maddie Ziegler Episode: What Really Happened in Homework & Hidden Talents

Why the Vinyl Experience Still Matters

If you’re listening to this on Spotify, you’re getting the notes, but you’re missing the vibe. The Bob Dylan Highway 61 Revisited LP was designed for the physical format. There’s a specific tension that builds as you flip the record from Side A to Side B.

Side A is the electric assault. "Tombstone Blues," "It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry," "Ballad of a Thin Man." It’s aggressive. It’s "thin wild mercury sound," as Dylan later called it.

Side B settles into something stranger and more atmospheric. "Queen Jane Approximately" is a sloppy, beautiful masterpiece of "who cares if the guitars are in tune?" And then, of course, the closing marathon.

Buying an original mono pressing is the holy grail for collectors. Why? Because the stereo mix back then was an afterthought. In the 60s, mono was the king. The mono version of Highway 61 is punchier. The drums hit harder in the center of the mix. It feels like a fist. The stereo version pans the instruments to the left and right in a way that can feel a bit disconnected, though many fans love hearing the separation of Bloomfield's guitar.

The Thin Man and the Identity Crisis

"Ballad of a Thin Man" is perhaps the most biting track on the record. "Because something is happening here / But you don't know what it is / Do you, Mr. Jones?"

Mr. Jones was the establishment. He was the critic. He was the guy trying to put Dylan in a box labeled "Protest Singer." This album was Dylan’s way of burning that box to the ground. He wasn't the voice of a generation anymore; he was a rock star with a sneer and a surrealist's eye.

✨ Don't miss: Kiss My Eyes and Lay Me to Sleep: The Dark Folklore of a Viral Lullaby

It’s fascinating to look back at the reviews from 1965. Some people were genuinely offended. They felt betrayed. Folk music was supposed to be "pure." It was supposed to be acoustic and earnest. Dylan showed up with a loud band and a bunch of lyrics that sounded like they were written on acid.

He didn't care.

Actionable Steps for the Modern Listener

If you want to actually "get" this album in 2026, don't just put it on in the background while you're doing dishes. It demands more.

- Find a Mono Pressing: If you can't afford a 1965 original (which can go for hundreds of dollars), look for the 2010 or 2015 Sundazed or Columbia mono reissues. They use the original master tapes and sound incredible.

- Read the Liner Notes: Dylan wrote a wild, stream-of-consciousness poem on the back of the jacket. It’s full of "the nightingale’s code" and "the circus is in town." It sets the mood better than any review ever could.

- Listen to "The Cutting Edge": If you really want to see how the sausage was made, check out The Bootleg Series Vol. 12: The Cutting Edge 1965–1966. You can hear the multiple takes of "Like a Rolling Stone" as it evolves from a slow waltz into the rock anthem we know today.

- Contextualize with the Neighbors: Listen to Bringing It All Back Home before it and Blonde on Blonde after it. This is the "Electric Trilogy." Highway 61 is the bridge—the moment where the fuse was lit.

The Bob Dylan Highway 61 Revisited LP isn't a museum piece. It’s not a dusty relic. It’s a living, breathing, snarling piece of art that still feels like it could cause a riot if you played it loud enough at the wrong party. It’s the sound of a man discovering he can do whatever he wants. And once Dylan realized that, music was never the same again.

To truly appreciate the depth of this era, compare the lyrical density of "Desolation Row" with the work of the Beat poets like Allen Ginsberg, who was a close friend of Dylan. You'll see that Dylan wasn't just writing songs; he was weaving a new American mythology. Grab a copy, drop the needle, and let the ghost of electricity howl.

Next Steps for Vinyl Enthusiasts

- Check the Matrix Numbers: When buying a used copy, look for "1A" or "1B" in the dead wax near the label. These are the earliest pressings and usually have the most dynamic range.

- Investigate the "Alternate" Like a Rolling Stone: Some very early promo copies and certain international pressings have slightly different fades or mixes.

- Setup Matters: Because this album is so mid-range heavy (the "thin wild mercury" sound), it sounds best on speakers with a strong warm profile rather than hyper-analytical digital monitors.