Hollywood was weird in 1969. The old studio system was dying, and the "New Hollywood" kids were taking over with cameras on their shoulders and a lot of questions about sex. If you want to understand where the modern obsession with ethical non-monogamy and "open relationships" actually started in the mainstream, you have to look at Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice. It’s more than just a period piece with great hats. It's a surgical strike on the concept of the nuclear family.

People remember it as "the wife-swapping movie." Honestly, that’s kind of a reductive way to look at it. Directed by Paul Mazursky, the film doesn't actually get to the "swapping" until the very end, and even then, it's not what you’d expect. It’s really a comedy of manners about two couples trying to be "hip" and "enlightened" while their internal hardwiring is screaming for traditional safety. It’s hilarious. It's awkward. And 50-plus years later, it’s still remarkably accurate about how humans fail at communication.

The Esalen Effect and the "New" Marriage

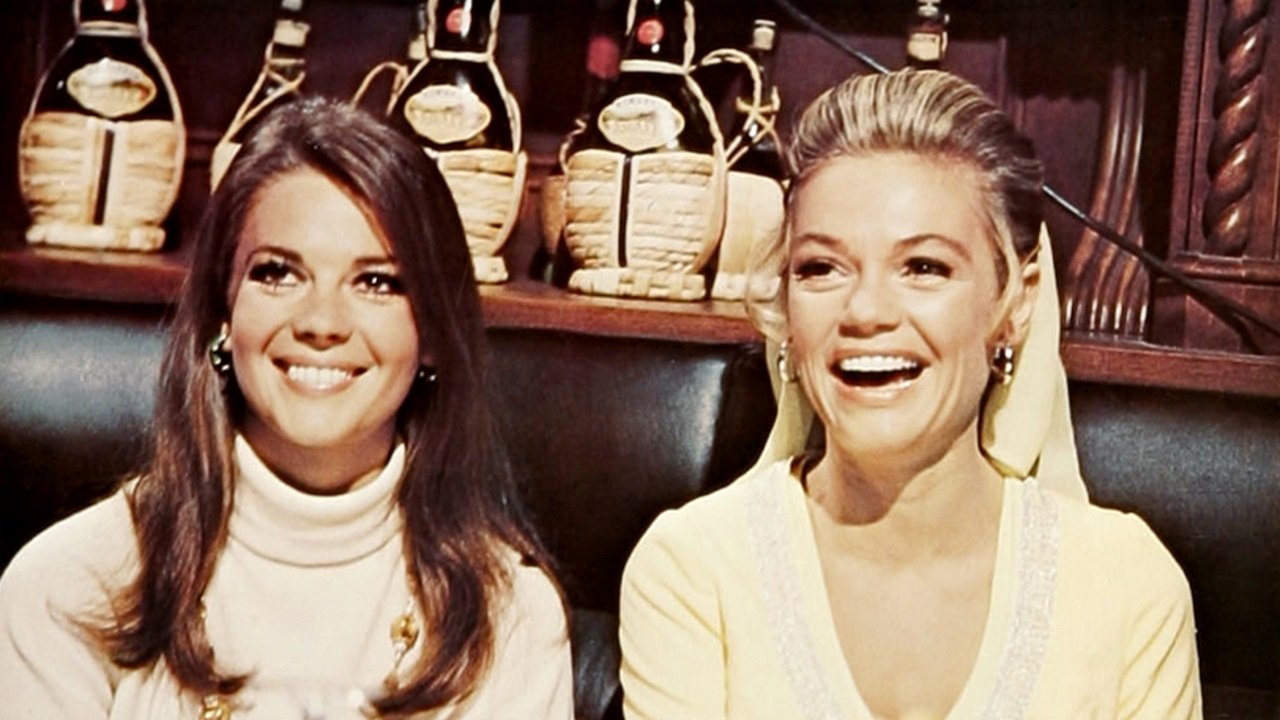

The movie kicks off with Bob and Carol, played by Robert Culp and Natalie Wood, attending an emotional retreat that looks suspiciously like the Esalen Institute in Big Sur. They spend 24 hours crying, hugging, and learning to "reach out" to people. When they get home, they feel like they’ve unlocked a secret level of humanity. They decide to be totally, brutally honest with each other. Bob admits to an affair. Carol, instead of throwing a lamp at his head, thanks him for his honesty. They’re "evolved."

Then they try to sell this new lifestyle to their best friends, Ted and Alice, played by Elliott Gould and Dyan Cannon.

This is where the movie gets brilliant. Ted and Alice represent the average American audience of 1969. They’re horrified, then curious, then eventually sucked into the vacuum of "free love." You’ve probably met people like this. The ones who go to one therapy session or read one book on polyamory and suddenly think they’ve transcended jealousy. Mazursky mocks this beautifully. He shows how Bob and Carol use "honesty" as a weapon to make themselves feel superior to their friends.

Why the Acting Feels So Uncomfortably Real

If you watch Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice today, the first thing you’ll notice is the pacing. It’s slow. Not boring slow, but uncomfortable slow. There’s a legendary scene involving a dinner party that feels like it lasts an hour. The camera just lingers on their faces as they navigate the silence.

📖 Related: Despicable Me 2 Edith: Why the Middle Child is Secretly the Best Part of the Movie

Dyan Cannon and Elliott Gould were both nominated for Academy Awards for a reason. Cannon’s portrayal of Alice is a masterclass in repressed anxiety. She spends half the movie looking like she’s about to have a nervous breakdown while trying to smile through the "progressive" conversations. Gould, on the other hand, plays Ted with this wonderful, shlubby skepticism. He’s the guy who just wants to have a drink and not talk about his feelings, but he’s eventually worn down by the sheer peer pressure of being "modern."

Robert Culp and Natalie Wood had to play the "straight" roles, which is actually harder. They have to believe in their own nonsense. Wood, especially, captures that specific 1960s California vibe—the silk scarves, the breathy voice, the desperate need to be seen as someone who "understands."

The Bedroom Scene: A Lesson in Cinematic Tension

The climax of the film—and the part everyone talked about at the water cooler in 1969—is the four of them in one king-sized bed at a Las Vegas hotel. By this point, the logic of the movie has dictated that they must have an orgy. It’s the only "enlightened" path forward.

But Mazursky does something genius. He doesn't make it sexy. He makes it clinical. He makes it quiet. You see four people who genuinely love each other but have no idea how to navigate the social script they’ve written for themselves. They’re performing.

"We're going to have an orgy, and we're going to have it now!" - Alice

👉 See also: Death Wish II: Why This Sleazy Sequel Still Triggers People Today

That line isn't an invitation to pleasure; it’s a demand for resolution. It’s a moment of peak absurdity. The movie argues that sexual revolution isn't just about sex; it's about the ego. It’s about wanting to be the kind of person who could do this, regardless of whether you actually want to.

Breaking Down the Legacy and the Box Office

Believe it or not, this was a massive hit. It earned over $30 million at the box office (which was huge back then) and was the fifth highest-grossing film of the year. It struck a nerve because the country was in the middle of a massive cultural shift. The "Summer of Love" had just happened. People were questioning the Vietnam War, the church, and the government. Marriage was the next logical target.

Critics at the time, like Pauline Kael, praised it for its sharp wit, though some felt it backed out of its premise at the very end. But that’s the point. The ending, set to the song "What the World Needs Now Is Love," features the characters walking through a crowd of strangers, looking at them with a newfound, slightly dazed sense of connection. It suggests that maybe the answer isn't "swinging," but just... empathy? Or maybe it’s a cynical take on how we all just perform for each other.

The Impact on Modern Film

Without Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice, you don't get movies like The Ice Storm or even shows like White Lotus. It pioneered the "cringe comedy" before that was even a term. It took the messy, sweaty reality of human relationships and put them under a microscope without the safety net of a traditional "happily ever after" or a moralistic punishment.

Common Misconceptions About the Film

Some people go into this thinking it’s an erotic film or a "sexploitation" flick. It’s definitely not. There’s very little nudity. The "R" rating back then was more about the themes and the language than the visuals. If you’re looking for a thrill, you’ll be disappointed. If you’re looking for a psychological autopsy of a marriage, you’re in the right place.

✨ Don't miss: Dark Reign Fantastic Four: Why This Weirdly Political Comic Still Holds Up

Another myth is that the movie advocates for swinging. Honestly, it does the opposite. It shows that most people are far too insecure and possessive to handle the reality of an open relationship. It exposes the narcissism inherent in "self-help" culture. Bob and Carol aren't better people at the end; they’re just more exhausted.

How to Watch It Like an Expert

If you're going to sit down with this classic, keep a few things in mind to get the most out of it:

- Watch the backgrounds. The production design by Pato Guzman is incredible. The houses are icons of late-60s California modernism. The decor tells you as much about the characters' fragile identities as the dialogue does.

- Listen to the silence. Mazursky uses long takes where nobody says anything. In an era of TikTok-fast editing, these scenes feel radical. Pay attention to the body language when the talking stops.

- Note the costumes. Moss Mabry’s costume design tracks the couples' descent into "hipness." Natalie Wood’s outfits become increasingly elaborate and "boho" as she tries harder to be free.

- Think about the year. 1969 was the year of the Manson murders and Altamont. The "peace and love" dream was curdling. The movie captures that exact moment when the party started to feel like a hangover.

Actionable Takeaways for Movie Buffs

To truly appreciate the DNA of Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice, you should pair it with other films from the same era to see how the conversation evolved.

- Step 1: The Comparison. Watch Mike Nichols' Carnal Knowledge (1971) right after. While Bob & Carol is a comedy, Carnal Knowledge is the dark, cynical flip side of the same coin.

- Step 2: The Director’s Cut. Look up Paul Mazursky’s other work, specifically An Unmarried Woman (1978). He had a unique ability to capture the female perspective in a way few male directors did at the time.

- Step 3: Analyze the Soundtrack. Quincy Jones did the score. It’s subtle, jazzy, and perfectly matches the "lounge" vibe of the era. Listen to how the music shifts from the rigid, classical sounds of the opening to the more fluid pop sounds of the ending.

The film serves as a time capsule, but it’s also a mirror. We’re still arguing about the same things today: how much honesty is too much? Can sex and love be separated? Is the traditional family unit dead? We’ve changed the terminology—we talk about "polyamory" and "situationships" now—but the underlying anxiety is exactly the same as it was in that Vegas hotel room in 1969.