Robert McCloskey had this weird, almost supernatural ability to make a Maine hillside feel like the center of the universe. If you grew up with a copy of the Blueberries for Sal book on your shelf, you probably remember that specific "kuplink, kuplank, kuplunk" sound. It isn’t just a cute bit of onomatopoeia. It’s the rhythm of a perfect picture book.

Published in 1948, this story has somehow survived the digital onslaught of the last century without losing an ounce of its charm. Why? Because it’s terrifyingly relatable for any parent who has ever lost track of a toddler for three seconds in a grocery store. Only in this case, the grocery store is a rugged mountain and the "other shopper" is a literal brown bear.

The genius of the mix-up on Blueberry Hill

Let's be real: the plot is basically a low-stakes parent's nightmare. Little Sal and her mother go up a mountain to pick berries for the winter. On the other side of the same mountain, a mother bear and her cub are doing the exact same thing. McCloskey uses a parallel structure that shouldn't work as well as it does, but because he keeps the stakes grounded in "child logic," it feels high-octane.

Sal wanders off because she's hungry. The bear cub wanders off because he's tired. They swap moms.

Most children's books today try to over-explain the "lesson" or inject some frantic energy into the prose. McCloskey does the opposite. He uses those gorgeous, deep blue-black ink illustrations—done in a single color because of post-WWII printing constraints—to let the landscape breathe. You can almost smell the pine needles and the sun-warmed dust. It’s a masterclass in pacing. The moment when the human mother realizes the "child" following her is actually a furry predator is a genuine heart-thumper for a four-year-old.

Why the art style matters more than you think

Actually, let's talk about that blue ink.

💡 You might also like: Easy recipes dinner for two: Why you are probably overcomplicating date night

McCloskey chose a specific shade of dark blue for the original drawings. It wasn't just a stylistic choice; it was practical. By using one color, he could create incredible depth through hatching and cross-hatching without the muddy mess of cheap 1940s color lithography. If you look closely at the rocks and the texture of the bear's fur, you see a level of craftsmanship that's mostly gone from modern, digitally-rendered books. It feels tactile. You want to touch the page to see if the blueberries are actually round.

What most people get wrong about the Blueberries for Sal book

People often categorize this as a "simple" nature story. It’s not. It’s actually a pretty profound look at the similarities between species.

A lot of critics at the time, and even some pedagogical experts today, look at the "mother swap" as a bit of fluff. But there’s a real undercurrent of biological reality here. Both mothers are preparing for a long winter. Both are distracted by the labor of survival. McCloskey, who lived on an island in Maine and spent his life observing the coast, didn't anthropomorphize the bears too much. They don't talk. They don't wear hats. They are just animals doing animal things, which makes the human-animal encounter feel much more "real" and slightly more dangerous than your average Goldilocks retelling.

- Little Sal is a proxy for every kid who has ever been "too busy" to keep up.

- The mother bear represents the sheer, unyielding drive of nature.

- The tin pail serves as the bridge between the two worlds—the "clink" of civilization versus the silence of the woods.

The Maine connection and Robert McCloskey’s legacy

You can't talk about the Blueberries for Sal book without talking about Brooksville, Maine. The setting isn't some generic forest. It’s specifically based on the area around McCloskey’s home on Scott Island. If you go to Maine today, you can still find those granite-topped hills covered in low-bush blueberries.

McCloskey won two Caldecott Medals in his career (for Make Way for Ducklings and Time of Wonder), but Blueberries for Sal remains the one people buy for baby showers. It’s the one that gets passed down until the spine is held together by scotch tape.

📖 Related: How is gum made? The sticky truth about what you are actually chewing

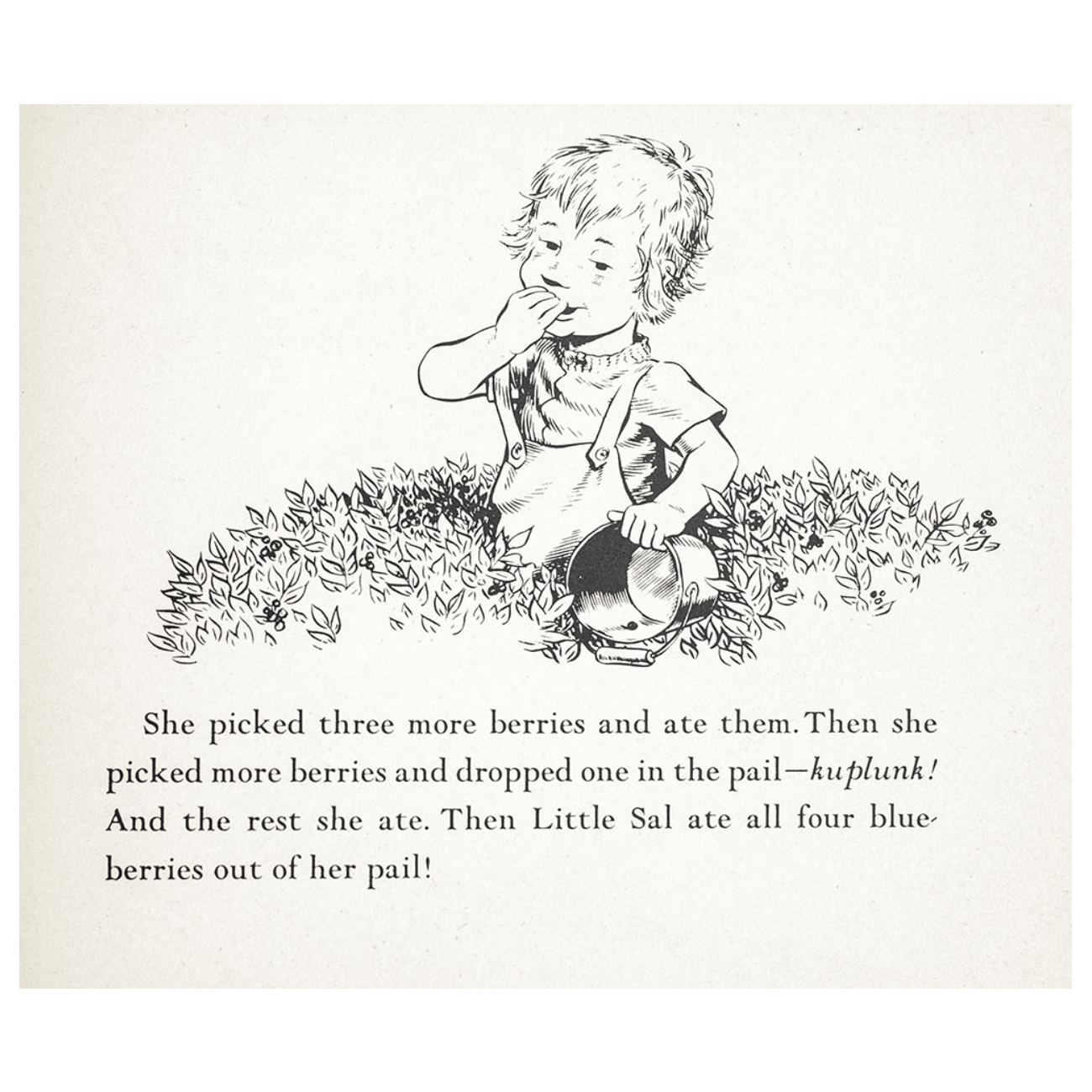

He was a perfectionist. Honestly, he’d spend years on a single book. He famously kept ducks in his bathtub in a Greenwich Village apartment just so he could study how they walked for his other famous book. For Sal, he used his own daughter, Sally, as the model. That’s why the movements of the little girl—the way she sits in the dirt, the way she drops a berry into her mouth—feel so authentic. It wasn't a guess. It was observation.

The psychology of "The Sound"

That "kuplink, kuplank, kuplunk" sequence is basically the first catchy pop hook in children’s literature. It’s a rhythmic device that teaches kids about gravity, volume, and the physical properties of metal hitting metal. When the pail is empty, it’s loud. As it fills up, the sound muffles.

Kids pick up on that. They understand the weight of the berries before they ever see the bucket full. It’s a sensory experience that most "educational" apps can't replicate. It forces the reader to slow down to the speed of a toddler's footsteps.

Is it still "safe" for modern kids?

Sometimes I hear parents worry that the book encourages kids to wander off or suggests that bears are "cuddly."

Look, kids aren't dumb. They see the mother's reaction when she realizes a bear is behind her. They see the bear's reaction when she realizes a human is behind her. The book actually reinforces a very healthy boundary: humans stay on their side, bears stay on theirs. It’s about mutual respect and the shared goal of getting through the winter.

👉 See also: Curtain Bangs on Fine Hair: Why Yours Probably Look Flat and How to Fix It

If anything, the book is an antidote to the "indoor childhood" epidemic. It makes the outdoors look like a place of adventure and sustenance, even if there’s a risk of a mix-up. It’s about the wildness of the world and how we fit into it, which is a pretty big theme for a book with fewer than 1,000 words.

Actionable ways to bring the book to life

If you're reading this book with a kid today, don't just flip the pages.

Grab a metal bucket and some marbles or dried beans. Let the kid drop them in. Ask them if they hear the "kuplink." It turns a reading session into a physics lesson without them even knowing it.

Also, if you can, find some actual Maine low-bush blueberries. They’re tiny. They’re nothing like those massive, water-filled globes you find in the supermarket in January. They’re tart and intense. Eating them while reading the book creates a "neurological anchor"—basically, they’ll remember the story every time they taste a blueberry for the rest of their lives.

- Focus on the "Noises": When reading aloud, exaggerate the silence of the bears versus the noise of the humans.

- Trace the Illustrations: Have the child follow the lines of the hills with their finger to understand the "up and over" journey.

- Discuss Winter Prep: Use the story to talk about where food comes from. Not just the store, but the earth.

- Compare the Moms: Talk about how the human mom and the bear mom are basically doing the same job.

The Blueberries for Sal book isn't just a relic of the 1940s. It’s a reminder that some things—hunger, curiosity, and the need for a mother’s presence—are universal, whether you have two legs or four. It’s a perfect piece of Americana that actually deserves its spot on the "all-time best" lists.

Next time you're in a bookstore, skip the flashy new releases with the neon covers for a second. Find the blue spine. Give it a squeeze. It’s still as solid as a Maine granite peak.

Next Steps for the Reader:

To truly appreciate McCloskey’s work, track down a high-quality hardcover edition rather than a digital scan; the depth of the blue ink is lost on backlit screens. If you've already mastered Sal’s story, move on to One Morning in Maine to see the characters grow up, or visit the Maine coastal region in late August to experience a real blueberry harvest firsthand.