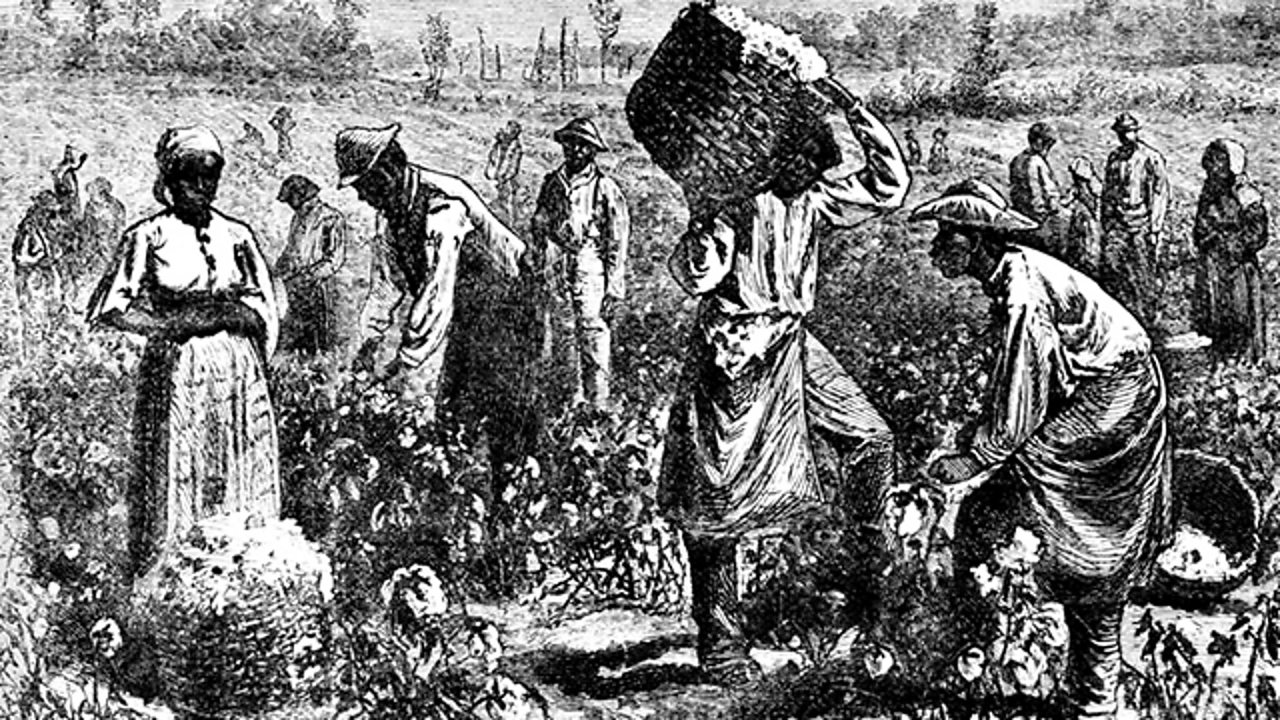

Images are heavy. They hold things words just can't quite capture, especially when you're looking at black slaves in america pictures from the mid-19th century. Honestly, it’s a weird feeling to stare at a daguerreotype of someone who was legally considered property. You see the grain, the stiff poses, and those eyes that seem to look right through the lens and into your living room.

These aren't just historical artifacts. They are pieces of a crime scene.

Most people think of photography as this neutral tool for recording life, but back in the 1840s and 50s, it was brand new tech. It was expensive. It was rare. When someone took a photo of an enslaved person, they usually had a specific—and often gross—reason for doing it. Maybe they wanted to show off their "wealth," or maybe a scientist wanted to prove some racist theory. Sometimes, though, it was the abolitionists trying to shock the world into waking up.

The Most Famous Photo You’ve Probably Seen

You know the one. It’s the image of a man named Peter (often called "Whipped Peter" or Gordon). He’s sitting sideways, back bare, and it looks like a topographical map of a nightmare. The keloid scars crisscross his entire back like thick ropes.

This specific example of black slaves in america pictures changed everything in 1863.

McPherson & Oliver, photographers based in Baton Rouge, took that shot after Peter escaped a plantation and made it to Union lines. When the Harper’s Weekly magazine published it, the North went into a frenzy. It was the first time many white Northerners actually saw what "discipline" looked like on a plantation. It wasn't a rumor anymore. It was silver-plated proof.

Think about the guts it took for Peter to sit for that. Photography back then required you to stay dead still for a long time. He had to hold that pose, exposing his deepest trauma to a cold glass lens, just so people who didn't know him might finally care about his humanity. It’s a gut-wrenching irony. To prove he was a person, he had to show how he’d been treated like an animal.

Why These Pictures Exist at All

Photography was a luxury. So, why would a slaveholder pay for a portrait of an enslaved person?

Kinda twisted, right?

Usually, it fell into a few buckets. You had the "nanny" photos. These are incredibly common in Southern archives. You see a Black woman, usually looking exhausted or stoic, holding a white baby. These were meant to project an image of "domestic harmony." The white families wanted to show that their "servants" were part of the family, even though they were legally owned. It’s a bizarre form of propaganda. The woman in the photo didn't have a choice to be there, and she likely had her own children she wasn't allowed to care for while she was busy posing with the master’s kid.

Then you have the scientific stuff. This is the dark side.

💡 You might also like: Why a Man Hits Girl for Bullying Incidents Go Viral and What They Reveal About Our Breaking Point

The Agassiz Daguerreotypes

In 1850, a Harvard professor named Louis Agassiz went to South Carolina. He wasn't there for the weather. He was looking for "specimens." He commissioned a photographer named Joseph Zealy to take portraits of enslaved Africans—men and women like Renty and his daughter Delia.

These were stripped-down, clinical, and dehumanizing. Agassiz wanted to prove "polygenism," the debunked idea that different races came from different origins. He used these black slaves in america pictures to argue that Black people weren't the same species as white people.

It’s disgusting. But it’s also a vital part of the record. These photos were lost in a Harvard museum attic until the 1970s. When they were found, they sparked a massive debate about who owns these images. Does the university own them because they paid for the camera work? Or do the descendants of Renty have a right to their ancestor’s likeness? It’s a legal battle that’s still making waves in the 2020s.

The "Hidden" Portraits

Not every photo was about pain or propaganda.

Sometimes, against all odds, enslaved people got their own pictures taken. It was rare, but it happened. Sometimes a sympathetic photographer would take a portrait, or a freed family member would save up enough to document a loved one.

In these rare cases, the vibe is totally different. You see a sense of pride. A hat tilted just right. A clean coat. These images break the mold because they weren't taken of them by an oppressor; they were taken for them.

You’ve gotta look for the small details.

Look at the hands.

Look at the way they hold their shoulders.

There’s a world of difference between a photo meant to be a "type" and a photo meant to be a person. If you look at the archives in the Library of Congress, you’ll find thousands of unidentified portraits. We don’t know their names. We don’t know where they ended up. But they existed. They stood in a room, breathed the air, and waited for the flash.

How We Look at These Images Today

Basically, we have to be careful.

Looking at black slaves in america pictures today is a bit like walking through a graveyard. You can’t just "consume" them as historical data. There’s a moral weight there. Scholars like Deborah Willis, who wrote The Black Female Body: A Photographic History, argue that we need to look at these images with "redemptive" eyes.

📖 Related: Why are US flags at half staff today and who actually makes that call?

We aren't just looking at "slaves." We are looking at people who were trapped in a system of slavery. That distinction matters.

If you spend enough time in the National Museum of African American History and Culture, you’ll see how they display these. They don’t just slap them on a wall. They provide context. They tell you who the photographer was and, if possible, who the subject was. They treat the images like the sacred, albeit painful, objects they are.

The Role of the Daguerreotype

The tech matters here.

Early photos were daguerreotypes—images on polished silver plates. They’re shiny. If you hold one in your hand and tilt it, you can see your own reflection in the metal behind the image of the enslaved person.

It’s a haunting metaphor. You’re literally looking at yourself while looking at them. It forces a connection across time. You can’t look away.

By the time the Civil War rolled around, we moved to "tintypes" and "cartedevisite." These were cheaper and made of paper or thin metal. This is when photography exploded. Suddenly, Union soldiers were carrying photos of their families, and Black soldiers—who had just escaped slavery—were posing in their new brass-buttoned uniforms.

Those are some of the most powerful black slaves in america pictures because they document the transition from "property" to "soldier." The change in posture is incredible. The person is the same, but the eyes are different. They own themselves now.

What Most People Get Wrong

People often think these pictures are "honest."

They aren't.

A photo is a choice. The person behind the camera chose the lighting. They chose the angle. They chose what to include and what to crop out. When you see a picture of an enslaved woman looking "content" in a kitchen, remember that there was likely a white man standing behind the photographer making sure she didn't move or frown.

👉 See also: Elecciones en Honduras 2025: ¿Quién va ganando realmente según los últimos datos?

It was a staged reality.

To find the truth, you have to look for the "puncture" in the photo—the little thing that doesn't fit the narrative. Maybe it’s a clenched fist hidden in a skirt. Maybe it’s a look of pure defiance that the photographer was too dumb to notice.

Understanding the Context

If you’re researching this, here’s how to actually get the full story:

- Check the Source: Was the photo taken for an abolitionist newspaper or a pro-slavery scientist? This changes everything about how the subject is framed.

- Look for the "Unseen": Enslaved people often used clothing to signal things. A specific headwrap or a piece of jewelry might have had deep cultural meaning that the white photographer completely missed.

- Cross-Reference: Many of the people in these photos also left behind "slave narratives." If you can match a face to a written account (like Frederick Douglass, who was the most photographed man of his century), the history becomes three-dimensional.

Where to Find Authentic Collections

If you want to see these for yourself—and you should, because seeing the physical reality of history is different than reading a textbook—there are a few key spots that handle this material with the respect it deserves.

- The Library of Congress: Their digital collection is massive. You can search by "Enslaved People" or "Daguerreotypes."

- The Getty Museum: They have a significant collection of early American photography that includes several rare portraits.

- The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture: Located in Harlem, this is probably the gold standard for African American historical imagery.

Practical Steps for Researching or Teaching This History

Don't just scroll through these images. It desensitizes you. If you're a teacher, a student, or just someone who cares about the truth, approach this with a plan.

First, slow down. Pick one photo. Spend ten minutes looking at it. What is the person wearing? What is the texture of their skin? What is in the background?

Second, read the metadata. Often, the most important info isn't in the picture; it's in the notes the photographer scribbled on the back of the plate.

Third, acknowledge the silence. Most of these people were never allowed to tell their own stories. The photo is often the only thing we have left of them. Treat it with that level of gravity.

Lastly, connect it to the present. These images laid the groundwork for how Black people were portrayed in media for the next hundred years. The tropes we see in old movies or even in modern news often have roots in how these 19th-century photographers decided to "frame" their subjects.

Understanding these pictures isn't just about the past. It’s about how we see each other right now. It's about recognizing the humanity that a camera can either highlight or try to hide.

To continue your research, examine the WPA Slave Narratives alongside these photos. The Federal Writers' Project in the 1930s interviewed the last living people who had been enslaved. Reading their words while looking at these mid-1800s faces provides a bridge between the visual record and the lived experience. You can also look into the Visual Studies of the African Diaspora at major universities to see how modern scholars are reinterpreting these archives to give the subjects back their agency.

For those looking to engage with this history through a more modern lens, the National Archives offers digital toolkits specifically designed to help researchers navigate the sensitive nature of these records without falling into the traps of historical voyeurism. Focus on the "provenance" of the images—knowing where a picture came from is just as important as what is in it.