Space is crowded. That sounds wrong, right? You look up at the night sky and see vast, empty voids between the stars. But in the messy, violent centers of galaxies, it’s a different story. Galaxies are constantly bumping into each other, merging over billions of years. When that happens, the supermassive black holes at their cores don't just vanish. They sink. They dance. They eventually find each other. Finding black hole pairs visual confirmation is basically the "Holy Grail" for astrophysicists right now, but it’s proving to be one of the hardest photos to snap in the history of science.

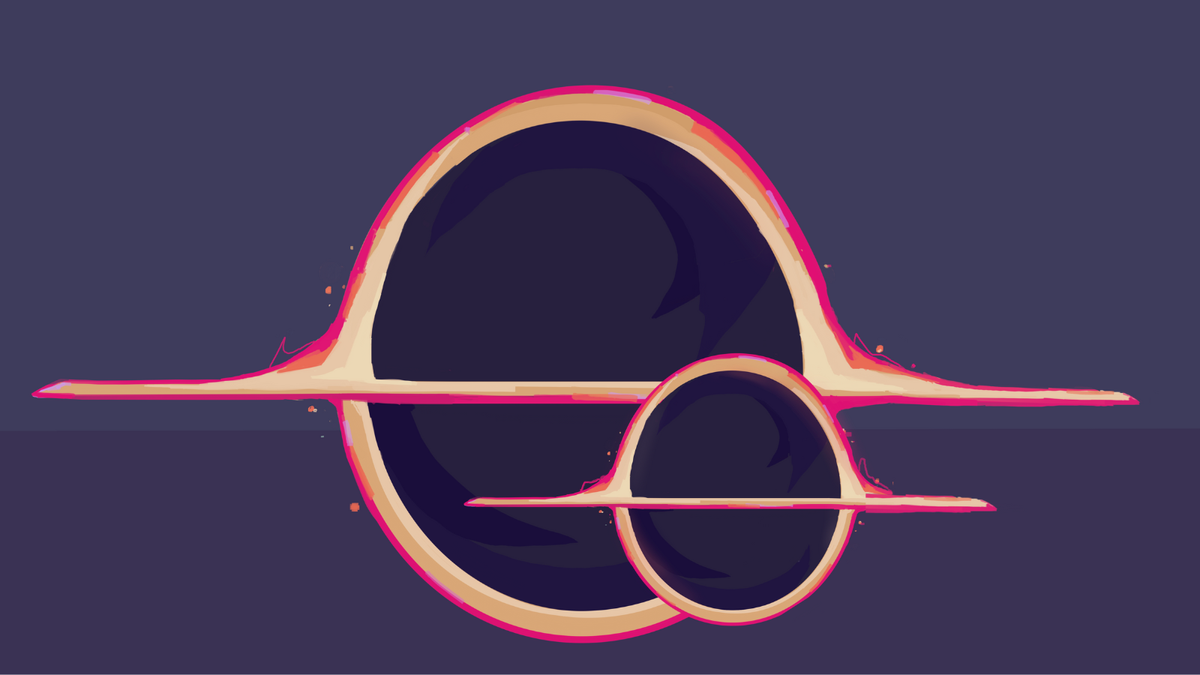

It’s not just about seeing one dark spot. We’ve done that. You probably remember the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) image of M87* or the milky swirl of Sagittarius A*. Those were single, lonely giants. The real drama happens when you have two of these monsters—each weighing millions or billions of times the mass of our Sun—circling one another in a gravitational tango.

Most of what we "know" about these pairs is math. It's code. It's a flickering light curve in a dataset that suggests something is eclipsing something else. But seeing is believing. Honestly, the scientific community is desperate for a clean, undeniable visual that proves these binary systems are exactly where our models say they should be.

The Problem With "Seeing" Nothing

How do you take a picture of two things that, by definition, don't let light escape?

You don't. Not directly.

When astronomers talk about a black hole pairs visual confirmation, they are actually looking for the "glow" around the holes. This is the accretion disk—a swirling, hot mess of gas and dust being ripped apart. If you have two black holes, you should have two disks. Or, if they are close enough, one giant, distorted disk feeding both.

The resolution required is insane. Imagine trying to see two individual grains of sand sitting on a beach in Los Angeles while you are standing on a skyscraper in New York. That’s the scale. We are looking for objects separated by maybe a few light-years (or less) located in galaxies millions of light-years away.

Why Radio Interferometry is the Only Way

Standard telescopes are useless here. They see a blurry smudge. To get the detail needed for a visual confirmation, researchers use Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI). This tech basically turns the entire Earth into one giant telescope dish by syncing up radio dishes in places like Hawaii, Chile, and the South Pole.

By combining the signals, they can achieve the angular resolution necessary to distinguish two distinct cores. But even then, the data is noisy. It takes years to process.

The Near Misses and "Almost" Discoveries

We’ve had some close calls. Take the galaxy 0402+379. For years, this has been the poster child for binary black holes. Back in 2006, and then again with follow-up data around 2017, researchers using the Very Long Baseline Array (VLBA) identified two distinct radio sources at the center of this galaxy.

They are separated by about 24 light-years. That’s huge in human terms, but on a galactic scale? They’re basically touching.

But is that a "visual confirmation" in the way the public wants? Not really. It looks like two bright dots on a grainy map. It doesn't show the interaction. It doesn't show the gravitational lensing or the warped space-time we see in movies like Interstellar.

Then there is OJ 287. This is a quasar that blinks. Every 12 years or so, it has a massive outburst. The theory—pioneered by Mauri Valtonen and his team—is that a smaller black hole is crashing through the accretion disk of a much larger one. We see the light from the impact. We see the timing match the math. But we still haven't "seen" the two individual shadows.

The Nanograv Breakthrough

Recently, the Pulsar Timing Array (PTA) efforts, like those from NANOGrav, basically confirmed a "hum" in the universe. This is the gravitational wave background. It's the collective roar of thousands of black hole pairs merging all over the cosmos.

It’s a sonic confirmation, sort of. But we are visual creatures. We want the pixel-perfect proof.

The Trouble With Dual Quasars

Sometimes we see two bright spots and get excited, only to realize we're being fooled. "Dual quasars" are common—these are black holes in merging galaxies that are still thousands of light-years apart. They haven't officially "paired up" into a binary system yet.

Distinguishing between two black holes that just happen to be in the same neighborhood and a true, bound binary system is a nightmare. A true binary system is gravitationally locked. They are doomed to collide.

- Distance: True binaries are often sub-parsec (less than 3.26 light-years apart).

- Velocity: They move fast. Their orbital speeds can be a significant fraction of the speed of light.

- Spectrum: Their light gets "redshifted" and "blueshifted" as they wobble toward and away from us.

Finding a black hole pairs visual confirmation means catching them in that final, tight spiral.

Why Should You Actually Care?

It feels like academic trivia, but it’s actually the key to understanding how galaxies grow. If black holes don’t merge easily—a problem called the "Final Parsec Problem"—then galaxies wouldn't evolve the way they do.

The math says that as black holes get closer, they should stall. They run out of gas and stars to interact with, and they just... sit there. Forever. But we know they merge because we’ve seen the ripples in space-time via LIGO.

Visual confirmation would bridge the gap between "we think this happens" and "we know exactly how it happens." It would show us how matter behaves in the most extreme gravity possible. It’s the ultimate physics lab.

What’s Next for the Hunt?

The next decade is going to be wild. We aren't just relying on ground telescopes anymore.

👉 See also: Changing Your TikTok Username: Why Your Brand Depends on It

The Event Horizon Telescope is getting upgrades. More dishes, higher frequencies. This means sharper images. There’s a legitimate chance that within the next few years, we will point the EHT at a known binary candidate and actually see two shadows.

Then there's LISA—the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna. This is a NASA/ESA project that will put a gravitational wave detector in space. Unlike LIGO, which hears "small" black holes (stars that collapsed), LISA will hear the supermassive ones. It will tell us exactly where to point our visual telescopes.

We are also waiting on the Vera C. Rubin Observatory. It’s going to scan the entire sky every few nights. It will find thousands of "flickering" quasars. Some of those flickers will be the unmistakable signature of two black holes eclipsing each other.

How to Track This Progress Yourself

If you want to stay on top of the search for black hole pairs visual confirmation, you have to look past the clickbait headlines. Most "discovery" articles are just rehashes of old data.

Keep an eye on the arXiv pre-print server. Specifically, look for papers mentioning "VLBI imaging" or "sub-parsec binary candidates." Scientists usually post their raw findings there months before they hit the mainstream news.

Follow the EHT Collaboration updates. They are the ones with the best shot at a literal photograph. They've already proven they can image a single black hole; a binary is the logical next step.

Monitor the "Tidally Disrupted Event" (TDE) reports. Sometimes, a star wanders too close to a binary pair and gets shredded. The way the light from that shredding "stutters" can provide a visual map of the two black holes.

The reality is that we are living in the era where "invisible" things are finally becoming visible. We are moving from artists' impressions to actual photons. It’s messy, it’s grainy, and it’s usually a shades-of-grey radio map, but it’s real. And in a universe this big, seeing is the only way to truly understand the scale of the chaos we're living in.

Keep your expectations in check for "4K photos." A visual confirmation will likely look like two blobs of light that shouldn't be there, moving in a way that defies Newtonian physics. But for an astronomer, those two blobs are more beautiful than any CGI render. They are the proof that the heaviest objects in the universe are finally ready for their close-up.