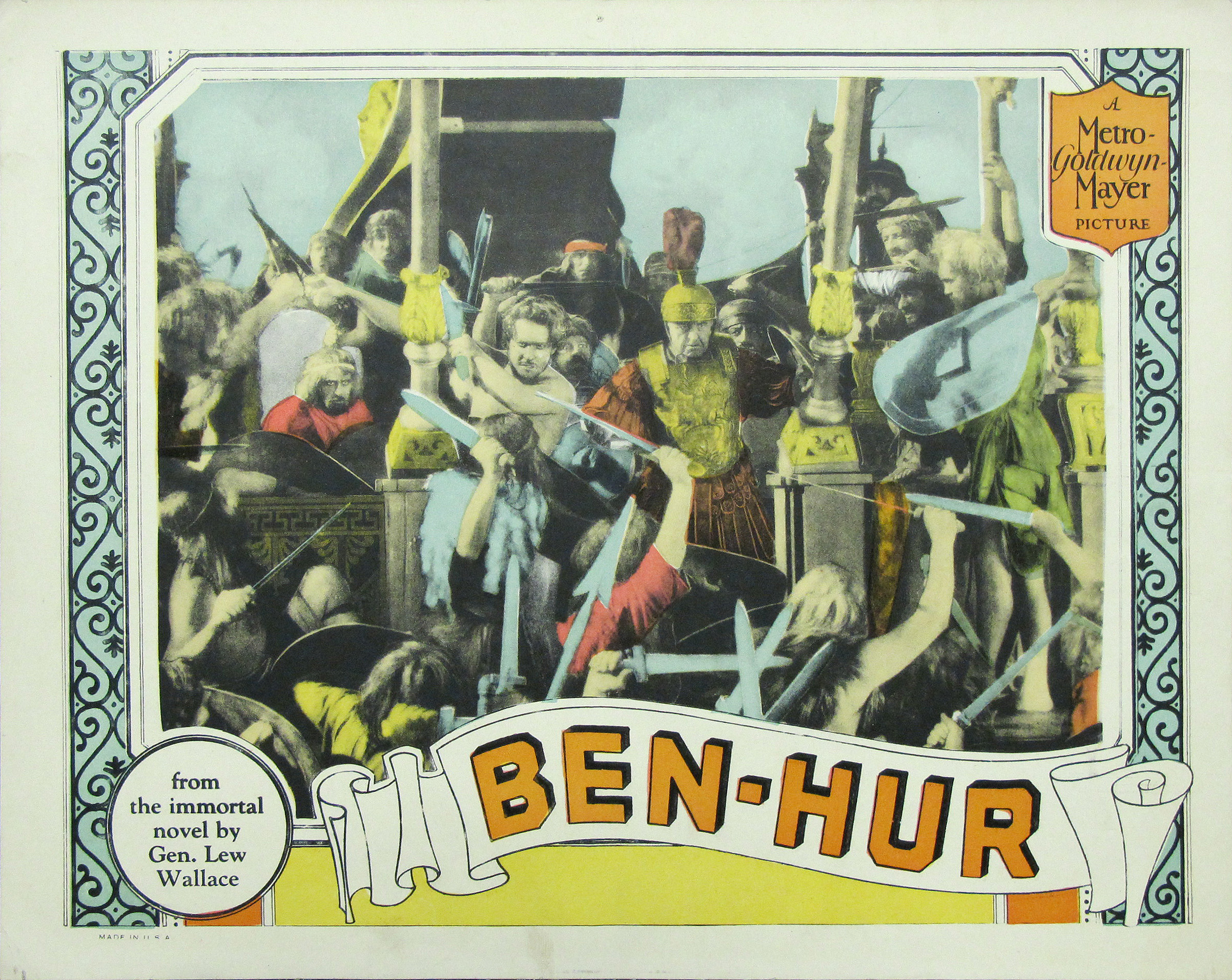

If you think modern Hollywood is obsessed with bloated budgets and chaotic sets, you really need to look at Ben Hur A Tale of the Christ 1925. It wasn't just a movie. Honestly, it was a multi-year logistical nightmare that almost bankrupted a studio before it even finished. People talk about the 1959 version with Charlton Heston—and yeah, that one is a masterpiece—but the silent version is where the real madness happened. It’s got everything: a revolving door of directors, a massive fire at sea, and a chariot race that remains one of the most dangerous things ever captured on celluloid.

Basically, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) put their entire existence on the line for this. They had to. The production started in Italy under the direction of Charles Brabin, but it was a disaster. The sets were wrong. The lighting sucked. The pace was glacial. Eventually, the studio heads got fed up, fired almost everyone, and brought in Fred Niblo to save the wreckage. Imagine spending millions of dollars in 1920s money just to realize you have to start over from scratch. That’s the kind of pressure we’re talking about here.

The Chariot Race That Changed Everything

You can’t talk about Ben Hur A Tale of the Christ 1925 without mentioning the chariot race. It is the heart of the film. Even today, with all our CGI and green screens, this sequence feels terrifyingly real because, well, it mostly was. They offered a $100 prize to the stunt drivers to win the race for real, which, looking back, was a recipe for absolute carnage.

You see these massive wooden wheels splintering and horses galloping at full tilt. It wasn’t just "movie magic." During the filming at the "Circus Maximus" set built in Culver City, one of the most famous crashes in cinema history occurred. A wheel snapped off a chariot, sending the driver flying and the horses tumbling. It’s actually in the final cut of the movie. They kept it because it looked too good—and too real—to throw away. Legend says several horses had to be put down, and the safety standards were essentially non-existent. It was beautiful, high-stakes chaos.

Fred Niblo didn't just use one camera. He used 42. He had cameras buried in pits, cameras on moving platforms, and cameras held by people who were probably praying they wouldn't get trampled. This set the template for how action was shot for the next hundred years. If you watch the 1959 remake, you’ll notice they copied the 1925 choreography almost beat-for-beat.

📖 Related: Isaiah Washington Movies and Shows: Why the Star Still Matters

Technicolor in the Silent Era?

Most people assume silent movies are just grainy black-and-white reels. That’s a total misconception. Ben Hur A Tale of the Christ 1925 used Two-Color Technicolor for several of its most important sequences, particularly the scenes involving Jesus and the grand processions. It’s sort of a surreal, painterly look—lots of reds and greens that pop against the sepia tones of the rest of the film.

It was incredibly expensive. It was also finicky. But the effect was profound for audiences in 1925. Seeing "The Christ" in color (even if his face was never fully shown, per the religious sensitivities of the time) felt like a miracle to the average moviegoer. It elevated the film from a standard action flick to something that felt divine.

The Sea Battle and Actual Fire

Before the production moved back to California, they tried to film the great sea battle in the Mediterranean. It was a mess. They built real, full-scale Roman galleys. The problem? They weren't exactly seaworthy in rougher waters. During a scene where the ships were supposed to be set on fire, the flames got out of control.

The extras—many of whom were locals who didn't speak English—panicked. They thought they were actually going to burn to death. People started jumping overboard in full armor. There are stories of production assistants frantically trying to fish people out of the water while the cameras kept rolling. It’s one of those "how did nobody die?" moments that plagued the early years of the industry. Actually, rumors have persisted for decades that people did die, though MGM did their best to keep any official fatalities off the record to avoid a PR nightmare.

👉 See also: Temuera Morrison as Boba Fett: Why Fans Are Still Divided Over the Daimyo of Tatooine

Ramon Novarro vs. Francis X. Bushman

The chemistry—or rather, the intense rivalry—between the lead actors is what keeps the story grounded. Ramon Novarro played Judah Ben-Hur. He was the "Latin Lover" archetype, sensitive and resilient. On the flip side, you had Francis X. Bushman as Messala. Bushman was a massive star with a huge ego to match.

Bushman reportedly took the role of the villain because he knew the chariot race would make him immortal. He was right. He played Messala with a sneering, muscular arrogance that makes you genuinely hate him. Off-camera, the tension was palpable. Novarro was younger and felt the weight of the studio's future on his shoulders, while Bushman was the established titan. That friction translates perfectly to the screen. You can feel the heat when they stare each other down before the race starts.

Why This Version Still Holds Up

Look, the 1959 version has the score by Miklós Rózsa and the widescreen grandeur. I get it. But the 1925 film has a raw, experimental energy that you just don't get once movies became a perfected science. It feels like you’re watching the birth of the "Blockbuster."

The sheer scale of the sets is mind-blowing. They didn't have Photoshop to fill in the crowds. If you see 10,000 people in the stands, there were 10,000 people there. The logistics of feeding, clothing, and directing that many extras in 1925 is a feat of engineering as much as art. It’s a testament to the ambition of the silent era. They didn't know what was impossible yet, so they just tried everything.

✨ Don't miss: Why Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy Actors Still Define the Modern Spy Thriller

- The Cost: It ended up costing around $4 million. In today's money, that’s a staggering amount for a film that had no guarantee of success.

- The Impact: It saved MGM. The success of Ben Hur A Tale of the Christ 1925 established them as the "prestige" studio, a reputation they leaned on for decades.

- The Editing: The way the chariot race is cut is incredibly modern. Rapid-fire shots, close-ups of the wheels, and wide shots of the stadium are edited together to create a sense of speed that still works.

Making Sense of the Religious Angle

The subtitle "A Tale of the Christ" isn't just for show. The film is deeply rooted in the novel by Lew Wallace. It tries to balance the pulpy revenge story of Judah Ben-Hur with the life of Jesus. It's a tricky needle to thread.

By keeping Jesus as a peripheral, almost ethereal figure, the film avoids being too "preachy." Instead, it uses His presence as a catalyst for Judah's internal change. It’s about the shift from wanting to kill your enemies to finding a way to live beyond that hatred. For an audience in 1925, many of whom had lived through the horrors of World War I, that message of finding peace amidst total destruction probably hit pretty hard.

Honestly, the film is a bit long. It’s over two hours, which can be a lot for a silent movie if you aren't used to the pacing. But if you give it a chance, the visual storytelling is so strong you eventually forget there’s no dialogue. You don’t need to hear Messala’s taunts to know he’s a jerk. You don’t need to hear the horses to feel the thunder of their hooves.

How to Experience Ben Hur Properly Today

If you’re going to watch Ben Hur A Tale of the Christ 1925, don’t just find some random, low-quality upload on a video site. The restoration work done on this film is incredible. You want to see those Technicolor strips in their full glory.

- Seek out the 2005 restoration. This version was meticulously cleaned up and features the original color tints and Technicolor sequences.

- Listen to the Carl Davis score. A silent film is only as good as its accompaniment. Davis’s score for this movie is sweeping, dramatic, and fits the scale of the images perfectly.

- Watch the 1959 version afterward. It’s a fascinating exercise to see which shots William Wyler (who actually worked as an assistant on the 1925 set!) decided to recreate decades later.

- Pay attention to the background. The sheer amount of detail in the Roman costumes and the architecture is insane. Most of that was handcrafted.

There is a certain tragedy to these old epics. Most of the people involved—the extras, the horse handlers, the cameramen—are long gone, but their work on Ben Hur A Tale of the Christ 1925 remains this permanent, massive monument to human ego and creativity. It’s a reminder that sometimes, the struggle to make the art is just as compelling as the art itself. If you want to understand where the modern movie industry came from, you have to start here. It’s the DNA of every action movie you’ve ever loved.