If you’ve ever woken up in the middle of the night, stumbled toward the kitchen for a glass of water, and realized you have no idea how you got there, you’ve had a tiny taste of the drama in La Sonnambula. Except, in Vincenzo Bellini’s 1831 masterpiece, the stakes are way higher than a stubbed toe. We’re talking about a Swiss village, a wedding on the rocks, and a woman walking across a literal high-wire mill bridge while fast asleep. It’s wild.

People often dismiss bel canto opera as just a bunch of singers showing off with flashy high notes. Honestly, that’s a mistake. La Sonnambula isn’t just a vocal gymnastic routine; it’s a deeply weird, psychological look at how a community reacts when things don’t make sense. Bellini didn't just write tunes; he wrote "long, long, long melodies" (Verdi's words, not mine) that feel like they’re stretching out toward the horizon.

What Actually Happens in Bellini’s La Sonnambula?

The plot is basically a 19th-century sitcom mistake turned into a tragedy. Amina is an orphan, loved by everyone in her village, and she’s about to marry Elvino. Everything is perfect. Then, a stranger—Count Rodolfo—shows up at the local inn. That night, Amina, who is a chronic sleepwalker, wanders into the Count’s room and falls asleep on his sofa.

👉 See also: Edward Norton: Why the American History X Actor Changed Hollywood Forever

The villagers find her there. Naturally, they assume the worst.

Elvino is devastated. He calls off the wedding. He proposes to the local innkeeper, Lisa, out of spite. It’s messy. The only way Amina can prove her innocence is by sleepwalking again, this time in front of everyone, crossing a dangerous, rotting bridge over a mill wheel. If she falls, she dies. If she makes it, she’s "innocent." It’s a bizarre form of trial by ordeal that only makes sense in the heightened reality of opera.

The Sleepwalking Scene: "Ah! non credea mirarti"

This is the moment everyone waits for. Amina is asleep. She’s holding a bouquet of faded flowers Elvino gave her. She sings "Ah! non credea mirarti," a melody so fragile it feels like it might snap.

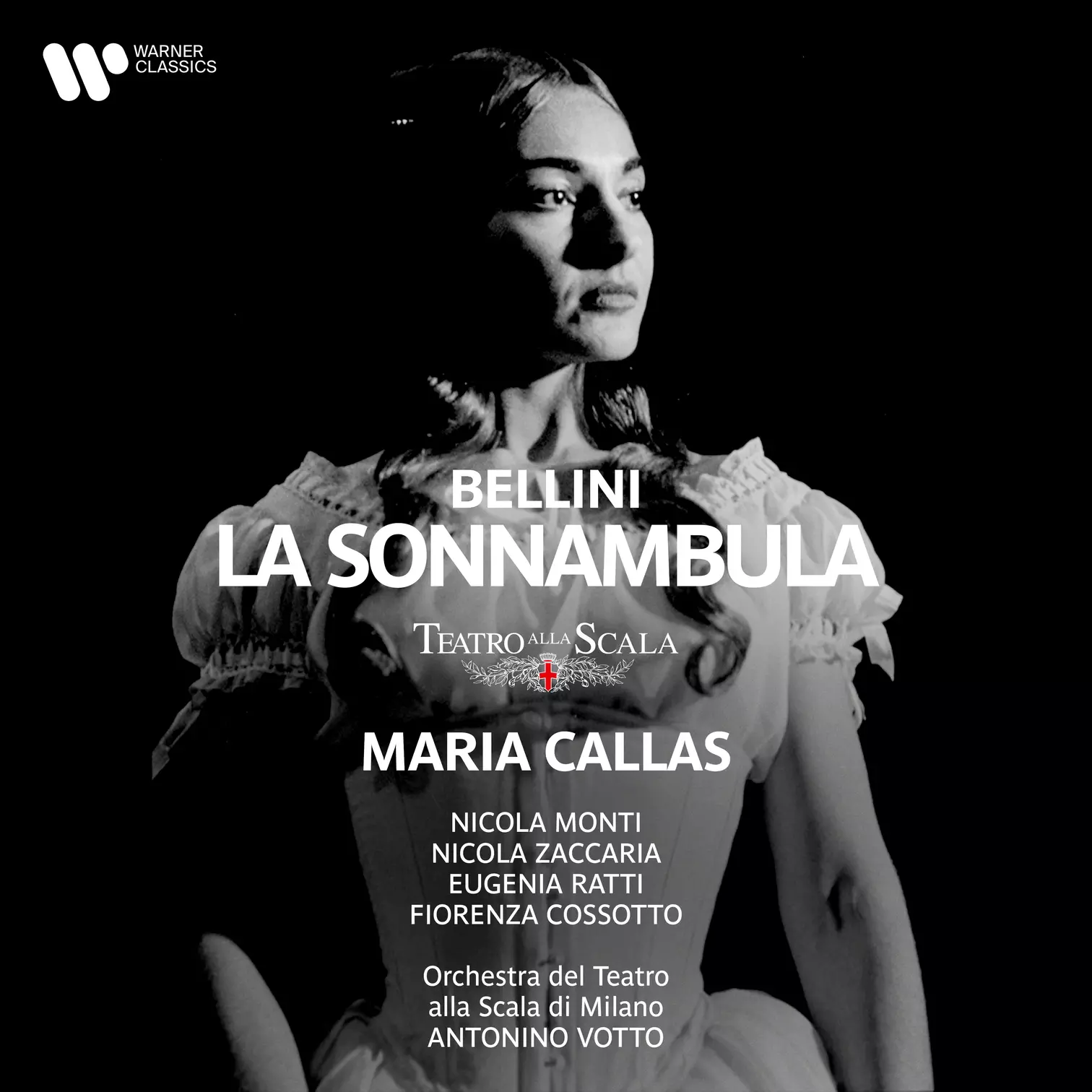

Maria Callas used to sing this with a sort of ghostly, hollow tone that made you forget you were sitting in a theater. She wasn't just singing notes; she was portraying a subconscious mind in pain. Then, she wakes up, realizes Elvino is back, and launches into "Ah! non giunge." This is the polar opposite—fast, ecstatic, and full of vocal fireworks. It’s the ultimate "I told you so" in musical form.

Why Bellini Wrote Like That

Bellini was a perfectionist. He didn't crank out forty operas like Donizetti. He wrote ten. He spent a lot of time with his librettist, Felice Romani, making sure the words and music were perfectly fused. In La Sonnambula, the music reflects the pastoral setting. You can almost hear the mountain air.

The orchestra isn't heavy. It’s light, allowing the voices to float. This is the essence of bel canto (beautiful singing). If the singer has to scream over a wall of brass, the magic of the sleepwalking atmosphere is ruined. Bellini’s orchestration is often criticized for being "simple," but it’s actually incredibly sophisticated in its restraint. He knows exactly when to stay out of the way.

The Callas vs. Sutherland Debate

You can’t talk about La Sonnambula without talking about the two titans who defined it in the 20th century: Maria Callas and Joan Sutherland.

Callas brought the drama. She made Amina a tragic figure, a woman whose world was collapsing. Her performance at La Scala in 1955, directed by Luchino Visconti, is legendary. She looked like a waif, a ghost haunting her own life.

Sutherland, on the other hand, was the "Voice of the Century." Her technique was flawless. Her trills were like machine guns. While Callas gave you the heartbreak, Sutherland gave you the sheer, unadulterated thrill of what the human voice can do. Both are "correct," but they offer totally different experiences. Honestly, you need to hear both to really get why this opera matters.

The Problem with the Ending

Let’s be real: Elvino is kind of a jerk. He doesn't believe Amina, he shames her publicly, and he immediately tries to marry someone else. When she proves her innocence by nearly dying on a bridge, he just says "My bad" and they get married.

Modern directors struggle with this. Some try to make Elvino more sympathetic, while others lean into the idea that the village is a claustrophobic, judgmental place. It’s not just a cute story about a sleepwalker; it’s a story about how quickly a community can turn on an outsider or someone who doesn't fit the "pure" mold.

How to Listen to La Sonnambula Without Getting Bored

If you’re new to this, don't try to watch a three-hour production in one sitting without a plan.

- Start with the finale. Watch a clip of the bridge crossing.

- Listen for the "long melodies." Try to find the end of a musical phrase. Bellini makes it hard; they just keep going.

- Ignore the plot holes. Yes, the Count could have just explained things immediately. Yes, the bridge is conveniently placed. It doesn't matter. Focus on the emotion.

Bellini’s La Sonnambula is a weird, beautiful relic of a time when melody was king. It’s about the things we do when we aren't conscious, and the cruelty of those who only see what’s on the surface.

Actionable Steps for the Aspiring Opera Buff

To truly appreciate this work, start by comparing three specific recordings of "Ah! non credea mirarti." Listen to Maria Callas (1955), Joan Sutherland (1962), and Natalie Dessay (2009). Notice the difference in "vocal color." Callas is dark and mourning; Sutherland is bright and crystalline; Dessay is frantic and fragile.

Next, look for the Metropolitan Opera's 2009 production directed by Mary Zimmerman. It’s controversial because it sets the opera in a rehearsal room, but it’s a great way to see how modern creators try to make sense of the 19th-century tropes. Finally, read the libretto while listening. The Italian is relatively simple, and seeing how Bellini stretches single words across dozen of notes will change how you hear the music forever. Don't just listen to the high notes; listen to the spaces between them. That’s where the real Bellini lives.