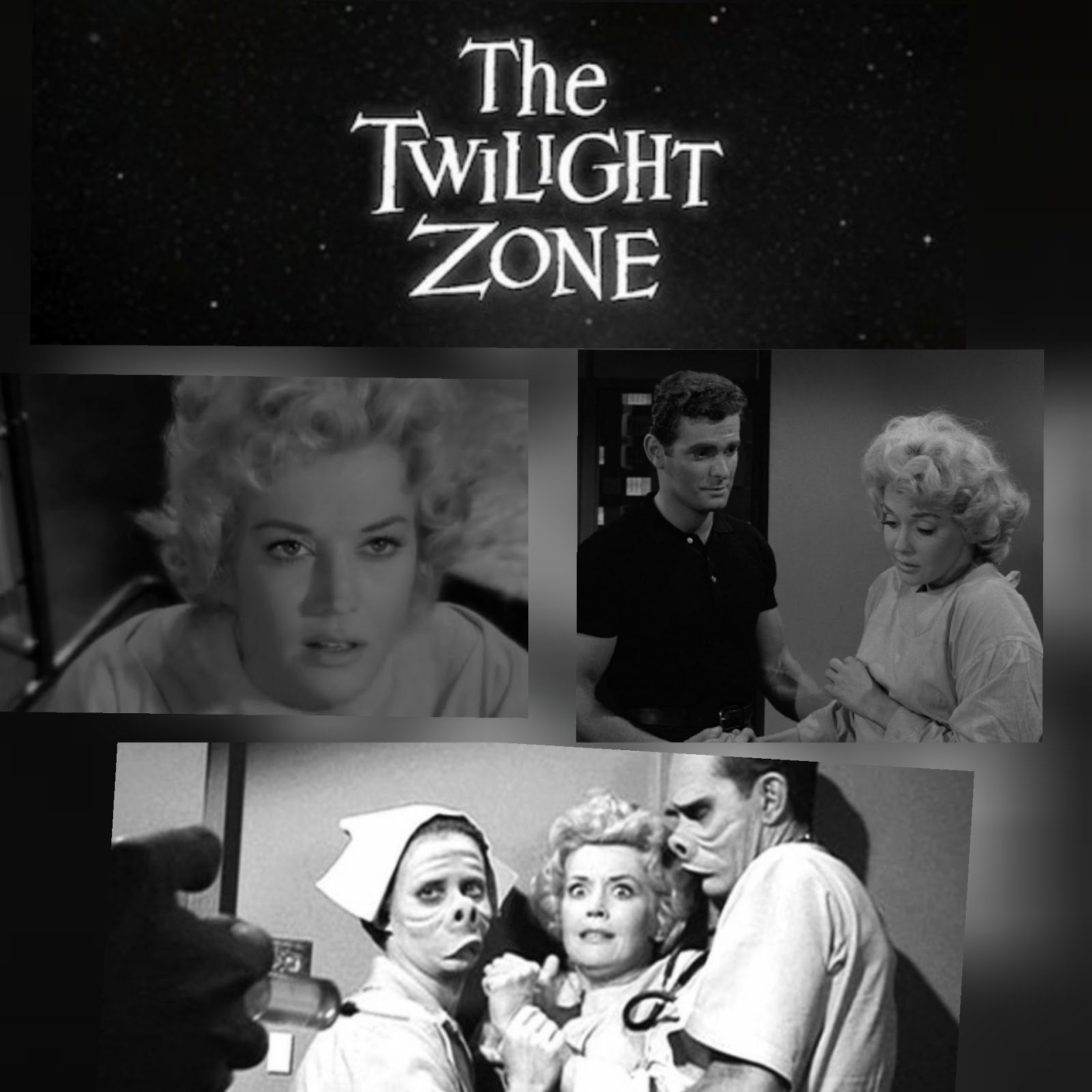

You know that feeling when a piece of black-and-white television hits harder than anything on Netflix today? That’s exactly what happens when you sit down with Beauty in the Eye of the Beholder. It’s arguably the most famous episode of The Twilight Zone, though most fans call it "The Eye of the Beholder." Rod Serling, the chain-smoking mastermind behind the series, didn't just want to scare us. He wanted to mess with our heads. He wanted to peel back the skin of 1960s American conformity and show us the rot underneath. Honestly, the episode is less about makeup and prosthetics and more about how terrifying a society becomes when it decides what "normal" looks like.

The premise is simple, yet the execution is a masterclass in tension. We meet Janet Tyler. She’s wrapped in bandages like a mummy, sitting in a dark hospital room. She has undergone her eleventh—and final—surgical procedure to "fix" her face. If this doesn't work, she's going to be exiled to a colony of "her own kind." For the first twenty minutes, we never see her face. We never see the doctors’ faces either. They are shadows. Silhouettes. Disembodied voices. Then, the bandages come off.

The Reveal That Changed Television Forever

When the bandages finally fall away, we see Donna Douglas. She is stunning. By every 1960s Hollywood standard, she is the pinnacle of beauty. But the doctors? They scream. They recoil in genuine horror. "No change!" they cry out in despair. Then the camera pivots. For the first time, we see the medical staff. They have sunken eyes, twisted pig-like snouts, and heavy, drooping jowls. To them, Janet Tyler is a monster.

It’s a gut-punch.

The brilliance of Beauty in the Eye of the Beholder lies in its subversion of the viewer's ego. We spent the whole episode sympathizing with Janet because we assumed she was "ugly" by our standards. We projected our own definitions of beauty onto her struggle. Serling trapped us. By making the "monsters" find the "beautiful" woman repulsive, he forced the audience to realize that our aesthetic values are completely arbitrary. They are social constructs. If you grew up in a world of pig-people, a straight nose and thin lips would look like a biological glitch.

👉 See also: The Let Em In Song: Why Paul McCartney’s Catchiest Earworm Is Actually a Family Tree

Behind the Scenes of a Sci-Fi Masterpiece

Creating this episode wasn't exactly a walk in the park for the crew at MGM. Douglas Heyes, the director, had to figure out how to film a twenty-five-minute show without showing a single face until the climax. It was a logistical nightmare. They used "subjective camera" angles, filming over shoulders or keeping characters in deep shadow.

The makeup was another hurdle. William Tuttle, the legendary makeup artist who later won an honorary Oscar, created those "pig" appliances. He needed something that looked humanoid enough to be "civilized" but different enough to be jarring. Interestingly, the actress playing the bandaged Janet Tyler for most of the episode wasn't actually Donna Douglas. It was Maxine Stuart. Stuart did the heavy lifting under the gauze, and Douglas only stepped in for the final reveal. This was a common Twilight Zone trick to save money and time, but it also added a layer of disconnectedness to Janet’s character that fits the theme of identity loss.

The Political Undercurrents Most People Miss

Rod Serling was a man obsessed with the dangers of McCarthyism and the "Red Scare." While Beauty in the Eye of the Beholder is often viewed as a commentary on plastic surgery or vanity, it’s actually a scathing critique of totalitarianism. Look at the "Leader" on the television screens in the hospital. He’s ranting about "the glorious oneness" and the need for "uniformity."

In Serling’s mind, the pig-people weren't just ugly; they were fascists.

The episode suggests that once a government or a culture decides on a single "correct" way to look, act, or think, anyone who falls outside that narrow margin is a threat. It’s a chilling thought. Janet Tyler isn't being "helped" by the doctors. She’s being assimilated. When the surgery fails, she isn't just a medical failure; she’s a political dissident. The hospital isn't a place of healing; it’s a re-education camp.

📖 Related: The My 600 lb Life TLC Reality: What Most People Get Wrong About Dr. Nowzaradan’s Patients

Why We Are Still Obsessed With This Episode

Fast forward to today. We live in an era of Instagram filters and "Snapchat dysmorphia." We are constantly "fixing" ourselves to fit a digital standard of perfection. The irony is that we are moving toward the very "uniformity" that Serling warned us about. We see the same lip fillers, the same contoured cheekbones, the same airbrushed skin across millions of profiles.

In a weird way, we are the doctors in the episode. We are the ones deciding that there is only one way to be "beautiful."

The legacy of Beauty in the Eye of the Beholder lives on because the fear of being "the other" is universal. We all have that nagging voice in the back of our heads wondering if we fit in. The episode tells us that "fitting in" is a trap. The ending is actually somewhat hopeful, though bittersweet. Janet is taken away by Walter Smith—a man who looks just like her—to a commune of people who share their features. They find a place where they aren't monsters. But they are still segregated. They are still outcasts from the "main" society.

Technical Prowess and Lighting

The cinematography by George T. Clemens deserves a shout-out. The high-contrast noir lighting was essential. Without those deep shadows, the mystery would have crumbled in the first five minutes. The way the light catches the metallic instruments and the clinical whiteness of the bandages creates a sterile, cold environment. It feels like a prison. Serling always insisted on high production values, and it shows. Even the music, a haunting score by Bernard Herrmann (the guy who did Psycho), keeps your teeth on edge.

Actionable Takeaways from Serling’s Vision

So, what do we actually do with this information? How does a 60-year-old TV show change how we live in 2026?

- Question the "Default": Whenever you feel "ugly" or "out of place," ask yourself who defined the standard you're measuring yourself against. Most of the time, it's a corporation trying to sell you a product or a social media algorithm designed to keep you scrolling.

- Audit Your Media Consumption: If your feed is nothing but "perfect" faces, you’re training your brain to see anything else as a deformity. Diversify what you look at.

- Recognize Conformity Traps: Look for areas in your life where you are trying to be "uniform" just to avoid the "Leader’s" gaze. True individuality is often found in the "deformities" we try to hide.

- Rewatch the Classics: Seriously. Go back and watch the original episode (Season 2, Episode 6). Look past the vintage effects and listen to the dialogue. It's sharper than most modern scripts.

The lesson of the pig-people is that perspective is a weapon. It can be used to exclude and destroy, or it can be used to see the inherent value in someone who looks nothing like you. Rod Serling ended the episode with one of his most famous narrations, reminding us that the "eye of the beholder" is a place where we all eventually reside. Whether we like what we see there is entirely up to us.

To truly understand the impact of this story, you have to look at the "state" of the world Janet Tyler lived in. It wasn't just a hospital; it was a dystopia. The next time you feel the pressure to look like everyone else, remember that in another world, you might be the "monster"—and that might be the most beautiful thing about you.

Don't just watch the show. Internalize the warning. The "glorious oneness" is a lie. The bandages are optional.

👉 See also: Original Moody Blues Members: The R\&B Roots Most Fans Completely Forget

To further explore the philosophy of The Twilight Zone, look into Rod Serling’s 1961 speech at UCLA regarding "The Social Responsibility of the Mass Media." He discusses how science fiction was the only way he could bypass censors to talk about racism and prejudice. Studying the history of the 1960-1961 television season provides even deeper context into the pushback he received for episodes like this one.

Follow this up by comparing this episode to "Number 12 Looks Just Like You" from Season 5, which takes the theme of forced beauty even further. Both episodes serve as a roadmap for maintaining your identity in a world that wants to erase it.