Look at the mud. If you ever find yourself staring at authentic battle of Shiloh pictures, the first thing that hits you isn't the glory or the flags; it’s the sheer, exhausting mess of the Tennessee spring. Most people expect to see mid-action shots of the "Hornet’s Nest" or General Albert Sidney Johnston falling from his horse. They want the drama.

They won't find it.

The cameras of 1862 weren't iPhones. They were massive, lumbering boxes that required glass plates and a chemistry lab on wheels. You couldn't just snap a photo while Minie balls were whistling through the peach orchard. Because of that, the visual record of Shiloh is a strange, haunting puzzle. It is a collection of "afters." It's a look at the scars left on the land and the hollowed-out eyes of the survivors.

Shiloh was a wake-up call for America. Before April 1862, everyone thought the Civil War might be a short, almost gentlemanly affair. Then came two days of absolute slaughter in the woods near Pittsburgh Landing. Over 23,000 men were killed, wounded, or went missing. To put that in perspective, that was more American casualties than the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, and the Mexican-American War combined.

When we talk about battle of Shiloh pictures, we are talking about the birth of modern war photography, even if the "action" is missing.

The Myth of the Action Shot at Shiloh

Let’s get one thing straight: there are zero photos of the actual fighting at Shiloh. None. If you see a grainy image of soldiers charging through the Sunken Road with smoke billowing everywhere, it's either a sketch from Harper’s Weekly or a photo of a reenactment from the 1960s.

Wet-plate collodion photography required the subject to stay still for several seconds. If a soldier moved to reload his rifle, he became a blur. If he ran, he vanished from the plate entirely.

So, what do we actually have?

We have the aftermath. Most of the iconic battle of Shiloh pictures were taken days or even weeks after the smoke cleared. Photographers like those working for Mathew Brady or independent operators arrived to find a landscape that had been chewed up and spat out. They captured the skeletons of trees. They captured the makeshift hospitals in log cabins.

🔗 Read more: At Home French Manicure: Why Yours Looks Cheap and How to Fix It

One of the most famous images shows the landing at Pittsburg Landing itself. You see the massive steamboats crowded along the Tennessee River. It looks peaceful, almost like a busy port scene. But when you look closer at the high-resolution scans provided by the Library of Congress, you see the sheer volume of supplies. You see the chaos of an army trying to feed itself after nearly being pushed into the water.

Why the "Sunken Road" Photos Matter

If you visit the Shiloh National Military Park today, you’ll see a peaceful, paved road. It’s beautiful. But the battle of Shiloh pictures taken in the late 19th century—some of the earliest "commemorative" shots—show a much more rugged terrain.

These photos are vital for historians. They show the specific density of the blackjack oaks that made the "Hornet's Nest" such a death trap. Without these visual records, we'd just be guessing about how the topography influenced the tactics. We can see exactly where the Confederate lines broke and where the Union artillery held the "Sunken Road."

It’s about the dirt. It’s always about the dirt.

Identifying Real Battle of Shiloh Pictures vs. Fakes

Honestly, the internet is full of mislabeled history. I’ve seen photos of Antietam labeled as Shiloh more times than I can count. How do you tell the difference?

- The Foliage: Shiloh happened in April. The trees should have early spring buds or be bare. If you see a photo with lush, heavy summer leaves, it’s not Shiloh.

- The Landmarks: Look for the Shiloh Log Chapel. It was a simple Methodist meeting house. Most photos of the "chapel" are actually of the 1930s reconstruction, but a few sketches and very early post-war photos show the original site’s layout.

- The Uniforms: By 1862, the "ragtag" look of the Confederacy wasn't quite as extreme as it would be in 1865, but you’ll see a mix of state-issued gear. If everyone looks perfectly outfitted in matching gray wool with piped collars, you're likely looking at a staged photo or a different theater of war.

The National Archives and the Library of Congress are the only places you should truly trust for verification. They hold the original glass negatives. When you see a "newly discovered" photo on a random blog, be skeptical. Usually, it's just a cropped version of a well-known plate of the Siege of Corinth.

The Faces of the 23,000

While we lack "combat" photos, we have an abundance of "soldier" photos. These are the small, palm-sized ambrotypes and tintypes men had taken before they marched into the Tennessee woods.

Think about a kid from Iowa. He’s 19. He goes to a studio in Des Moines, puts on a stiff new blue coat, and tries to look tough for his mom. That photo is, in many ways, a battle of Shiloh picture because that was the last time he was ever "whole."

💡 You might also like: Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen Menu: Why You’re Probably Ordering Wrong

Many of these photos were found on the battlefield. There are heartbreaking accounts of burial parties finding these small brass frames tucked into the pockets of the dead. These aren't just "pictures"; they are the last physical evidence of a human being who was erased in a peach orchard.

How to View These Images Today (and Why It’s Different)

Technology has changed how we consume the Civil War. We aren't just looking at faded sepia prints anymore.

Digital restoration has been a game-changer. Experts can now take a 160-year-old glass plate and scan it at such a high resolution that you can read the writing on a crate of hardtack in the background. You can see the individual buttons on a general's tunic.

The Colorization Debate

This is a hot topic among historians. Some people hate it. They think colorizing battle of Shiloh pictures is a form of desecration—that it makes the past look like a movie.

I disagree, mostly.

When you see the Tennessee mud rendered in its actual, sticky red-clay color, the battle feels real. It stops being a "history lesson" and starts being a tragedy. You realize the "Blue and Gray" were actually "Brown and Muddy." The red of the blood on the peach blossoms—which survivors wrote about for decades—becomes visceral.

However, you have to be careful with who does the colorizing. Amateur AI colorization often gets the uniform tints wrong. Union blue wasn't navy; it was a specific indigo that faded in the sun. Confederate "butternut" wasn't just brown; it was a yellowish-tan derived from copperas and walnut hulls.

Where to Find the Best Collections

Don't just Google it. Most of the top results are low-res garbage.

📖 Related: 100 Biggest Cities in the US: Why the Map You Know is Wrong

- The Library of Congress (LOC): Their "Civil War Glass Negatives and Related Prints" collection is the gold standard. You can download TIFF files that are massive.

- The National Parks Gallery: Specifically search for the Shiloh National Military Park archives. They have photos of the early monument dedications which show the land before it was manicured.

- The Gilder Lehrman Institute: They have excellent context for the images, explaining who the people in the photos actually were.

The Landscape as a Photograph

Sometimes the best battle of Shiloh pictures are the ones taken of the trees that survived. They are called "Witness Trees."

There are oaks still standing today that have lead bullets buried deep inside their trunks. When you take a photo of those trees, you are photographing a living witness to the 6th and 7th of April, 1862.

The topography of the park is remarkably well-preserved. Because it's so remote—it’s not like Gettysburg, which is right next to a bustling town—Shiloh feels trapped in time. When you stand at the Sunken Road and look toward the Confederate positions, you are seeing the exact sightline that a Union soldier saw.

Actionable Steps for History Buffs

If you're looking to dive deeper into this specific visual history, don't just be a passive scroller.

- Check the "Stereograph" Collections: In the 1860s, 3D was a thing. They used stereographs—two nearly identical photos mounted on cardstock. If you can find digital "side-by-side" versions, you can actually use a cheap VR headset or a stereoscope viewer to see the Shiloh battlefield in 3D. It’s eerie.

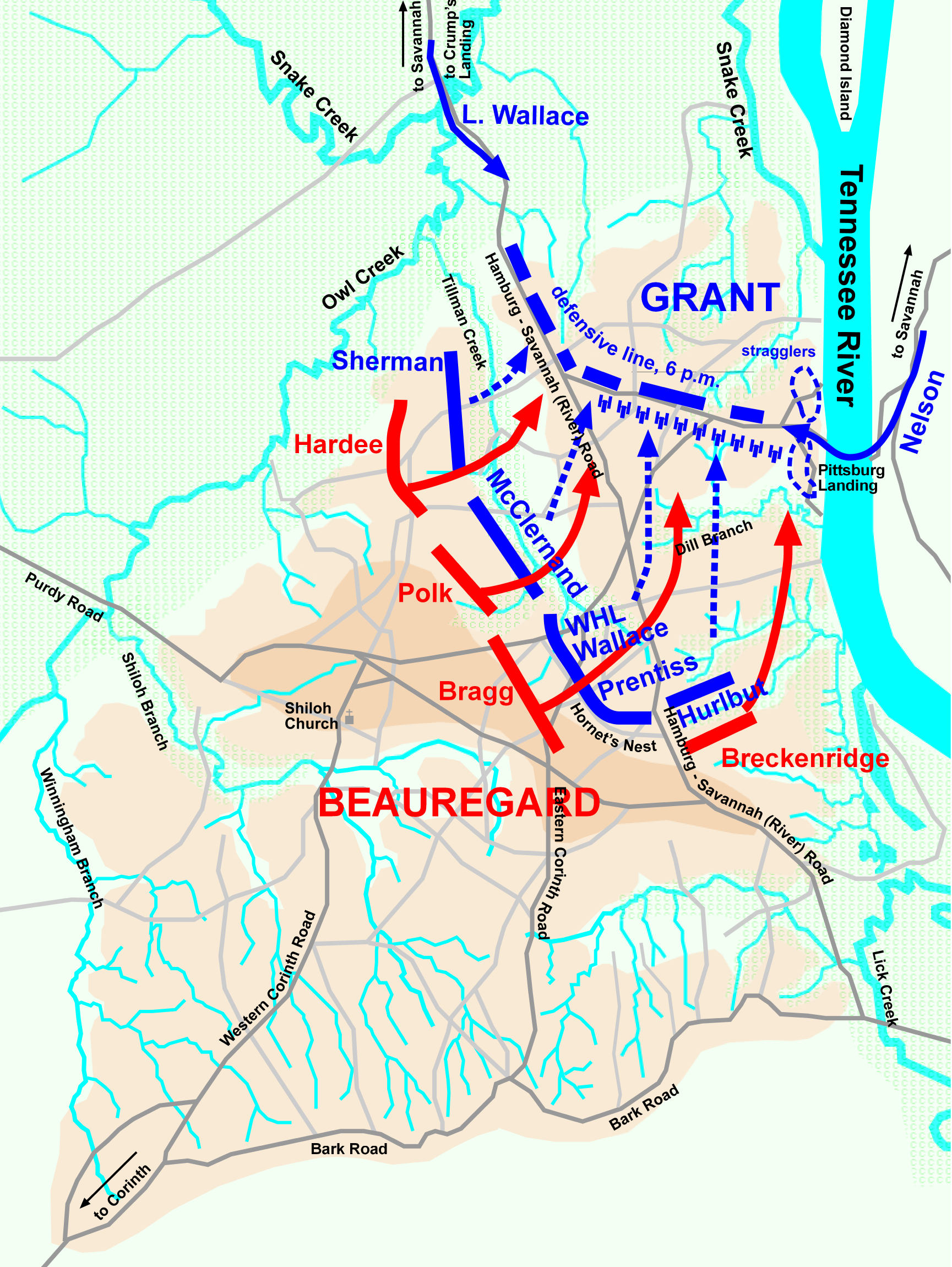

- Search for "The War of the Rebellion: Official Records": While these are mostly text, they often contain maps that were drawn based on the very first photos taken of the terrain. Comparing a 1862 map to a 1862 photo is the best way to understand the troop movements.

- Visit the "Shiloh in Color" Projects: Look for professional historians who specialize in digital restoration. They often provide "before and after" sliders that show the repair work done on cracked glass plates.

The reality of the American Civil War is often buried under layers of romanticism. We like the idea of brave men in clean uniforms. But the actual battle of Shiloh pictures tell a different story. They tell a story of exhaustion, of broken wagons, of scarred earth, and of a nation that was realizing, for the first time, exactly how much this war was going to cost.

Next time you see one of these photos, don't just look at the men. Look at the background. Look at the shattered branches and the churned-up soil. That’s where the real history is hiding.

To get the most out of your research, start by browsing the Library of Congress digital archives using the specific search term "Pittsburg Landing" rather than "Shiloh." Since the Union called the battle by the name of the landing, many of the earliest and most accurate contemporary photos are filed under that name. This simple keyword shift will unlock dozens of high-quality images that most casual researchers completely miss.