You’ve probably seen the haunting photos of the Civil War. Those stiff, unblinking portraits of young men in wool, or the grisly, bloated landscapes of Gettysburg and Antietam that made people in the 1860s lose their lunch. But if you start hunting for battle of Shiloh photos taken during the actual fight in April 1862, you're going to hit a brick wall pretty fast.

It’s a ghost hunt.

There are no photos of the fighting. None. Zero. While the Battle of Shiloh was one of the bloodiest, most chaotic mess-ups in American history, the "camera" wasn't there to catch the smoke. Photography back then was a slow, clunky, chemistry-heavy nightmare. You couldn't just whip out a phone. You needed a literal wagon full of glass plates and silver nitrates. Because Shiloh happened in the thick woods of Tennessee, far from the established studios of the East Coast, the visual record we have today is mostly a collection of "afters." We have the scarred trees and the muddy landings, but the "during" is left to our imagination.

The Mystery of the Missing Mid-Battle Shots

Why is it so hard to find authentic battle of Shiloh photos from the heat of the action? Honestly, it’s mostly down to logistics and the sheer terror of the location. Photographers like Mathew Brady or Alexander Gardner usually followed the armies in the Eastern Theater—Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania. Shiloh was the "West." It was the frontier.

To get to Pittsburg Landing, you had to take a steamboat down the Tennessee River. It wasn't a casual trip.

When the Confederates under Albert Sidney Johnston smashed into Ulysses S. Grant’s unsuspecting camps on the morning of April 6, 1862, there weren't any photographers set up on the perimeter. Even if there had been, the "wet plate" process required a subject to stand still for several seconds. If you're being charged by a line of screaming Mississippians with bayonets, "standing still" isn't exactly on the menu.

What we actually have are photos of the aftermath.

Most of what people call battle of Shiloh photos are actually shots of the Sunken Road or the Peach Orchard taken weeks, months, or even years later. One of the most famous images often associated with the site shows the massive Union supply base at Pittsburg Landing. You see the steamboats huddled against the bank like giant water bugs. It looks peaceful, but if you look closer at the churned mud and the stacked crates, you realize that just a few days prior, that very mud was soaked in the blood of 23,000 casualties.

💡 You might also like: Hotels Near University of Texas Arlington: What Most People Get Wrong

The Faces of the "Hornet’s Nest"

While we lack "action" shots, we do have the portraits. These are the most personal battle of Shiloh photos available. These weren't taken on the field; they were taken in hometown studios before the boys marched off.

Take a look at the tintypes of the 12th Iowa or the 55th Illinois. You see these kids—and they really were just kids—staring into the lens with a mix of bravado and absolute cluelessness about what was coming. At the "Hornet's Nest," a thicket of oak and brush where the fighting was so loud it supposedly sounded like a thousand angry bees, these boys held the line for hours.

When you look at their portraits today, knowing they ended up in a trench at Shiloh, the images take on a different weight. It’s not just a "historical artifact" anymore. It's a guy named Thomas who never went home to his farm in Galena.

Navigating the National Military Park Today

If you visit the Shiloh National Military Park today, you’re basically walking through a live-action version of those old photos. The park is one of the best-preserved battlefields in the United States. Because it’s so remote, it hasn’t been swallowed by suburban sprawl like many Virginia sites.

The most famous "photo ops" in the park now include:

- The Sunken Road: It’s not as deep as you’d expect, but the shadows under the trees still feel heavy.

- The Peach Orchard: There are still trees there, though obviously not the same ones that were shredded by Minie balls in 1862.

- Shiloh Church: A reconstructed log building stands where the original "Place of Peace" (which is what Shiloh means in Hebrew) became a scene of absolute slaughter.

- The National Cemetery: Perched on the bluffs overlooking the river, it’s where the men from those grainy portraits ended up.

Many people search for battle of Shiloh photos hoping to see the "Hornet's Nest" in its original state. You won't find it. What you will find are the 19th-century monuments. Interestingly, the veterans who survived the battle went back in the 1880s and 1890s to take photos of themselves standing where they fought. These "veteran photos" are actually some of the most moving images we have. You see old men with long white beards pointing at a specific tree, telling a photographer, "This is where my brother fell."

The Logistics of 19th-Century War Photography

We have to talk about the "Darkroom Wagon."

📖 Related: 10 day forecast myrtle beach south carolina: Why Winter Beach Trips Hit Different

To produce any of the battle of Shiloh photos that exist from the 1860s, a photographer had to coat a glass plate with collodion, rush it into the camera while it was still wet, expose it, and then rush back to the wagon to develop it before it dried. If the plate dried out, the image was ruined.

Imagine doing that while the ground is literally shaking from 12-pounder Napoleon cannons.

The few photographers who did make it to the Western Theater often focused on the dead. Why? Because the dead don't move. They were the only subjects that stayed still long enough for the slow shutter speeds of the era. It’s a grim reality, but it’s why the visual history of the Civil War feels so death-obsessed. It wasn't just a stylistic choice; it was a technical limitation.

How to Spot a Fake or Mislabeled Photo

The internet is full of "History" accounts that post photos and claim they are from Shiloh. Most of the time, they’re actually from Gettysburg or the Wilderness.

Here’s a quick tip: Look at the terrain.

Shiloh was fought in a "checkerboard" of small fields and dense, scrubby woods. If you see a photo with massive stone walls or wide-open rolling hills, it’s probably not Shiloh. Shiloh was a "soldier's battle," meaning the generals lost control almost immediately because they couldn't see through the brush. Any authentic battle of Shiloh photos of the landscape should look claustrophobic. They should feel tangled.

Another giveaway is the "Confederate dead" photos. There are very few verified photos of Confederate dead at Shiloh. Most of the famous "trench" photos were taken at places like Petersburg or Antietam. At Shiloh, the burial squads worked fast because of the April heat and the sheer number of bodies. They didn't wait for photographers to arrive from the North.

👉 See also: Rock Creek Lake CA: Why This Eastern Sierra High Spot Actually Lives Up to the Hype

Why the Lack of Photos Matters

Does the lack of "real-time" battle of Shiloh photos hurt our understanding of the fight?

Maybe.

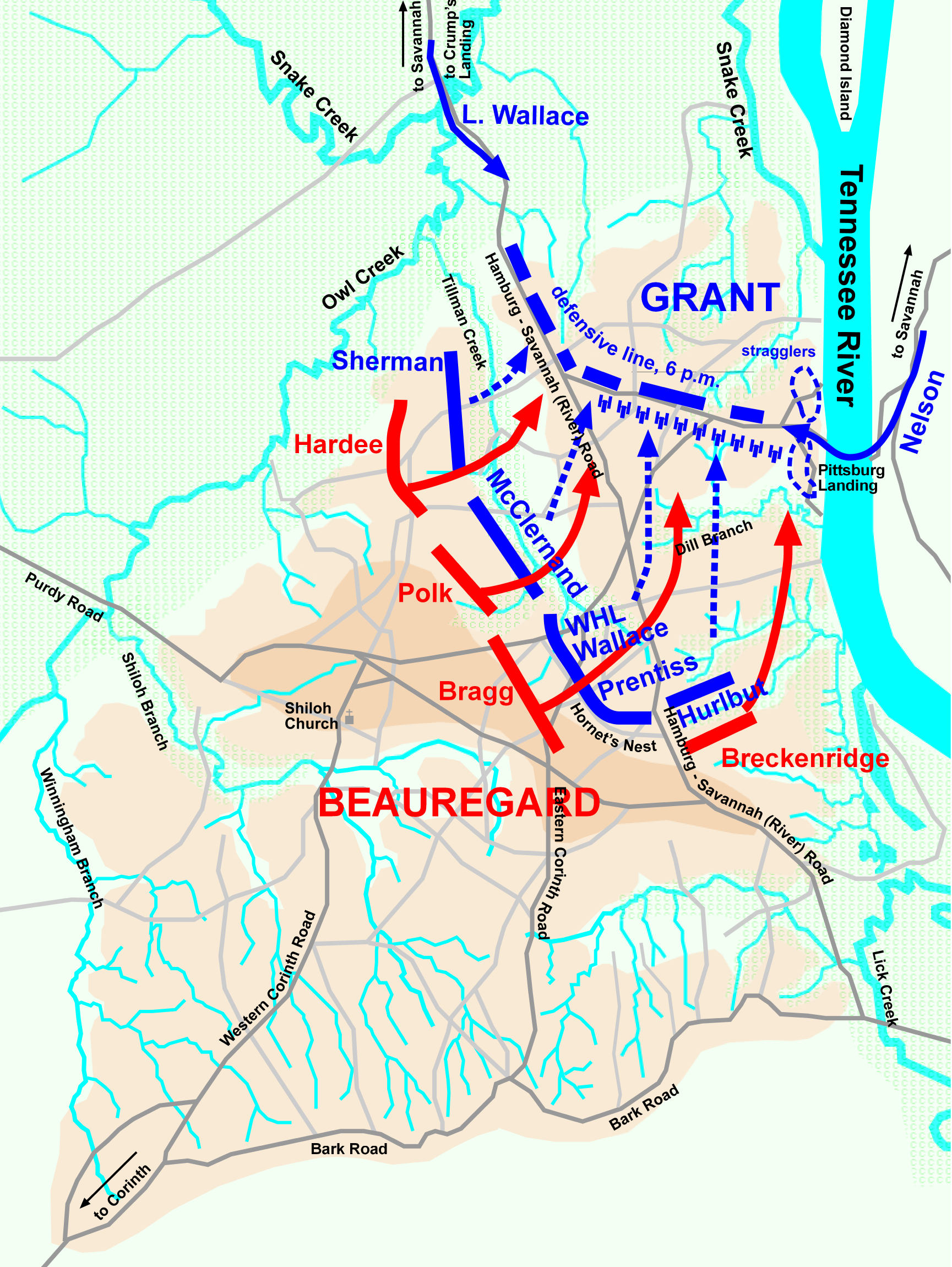

But in a way, it forces us to rely on the words of the people who were there. We have to read the letters. We have to look at the hand-drawn maps that look like they were made by someone with a shaking hand. When you combine those letters with the post-battle photos of the landscape, you get a more "human" version of the story than a single snapshot could ever provide.

Ulysses S. Grant wrote in his memoirs that the field was so covered in bodies that "it would have been possible to walk across the clearing, in any direction, stepping on dead bodies, without a foot touching the ground." No photo could ever truly capture that horror without losing the soul of the people involved.

Key Visual Resources for Researchers

If you're serious about finding the real deal, don't just use Google Images. Go to the source.

- The Library of Congress (LOC): They have the digitised glass plates from the Anthony-Taylor collection. Search for "Pittsburg Landing" rather than "Shiloh" to find the earliest shots.

- The National Archives: This is where the grim stuff lives—the medical photos of survivors and the official topographical surveys.

- The Shiloh National Military Park Archives: They have a collection of "then and now" images that are incredibly helpful for seeing how the forest has reclaimed the scars of 1862.

Actionable Steps for Your Own Research

If you’re looking to dive deeper into battle of Shiloh photos or even visit the site to take your own, here is how you should handle it:

- Check the Date: If a photo claims to be from the battle but shows "monuments," it was taken after 1894.

- Look for "Pittsburg Landing": That was the Union name for the site. Most contemporary photographers used that name for their captions, not "Shiloh."

- Visit in April: To see the landscape exactly as the soldiers saw it (minus the modern roads), go during the anniversary. The "Peach Orchard" blooms around that time, giving you a hauntingly beautiful contrast to the violence that happened there.

- Use the "Civil War Glass Studio" app: There are tools now that allow you to see what the light would have looked like for a photographer using 1860s equipment. It helps you understand why the photos we do have look so eerie.

The battle of Shiloh photos that do exist are fragments of a shattered mirror. They don't give us the whole picture, but they give us enough to know that we never want to see a scene like that in person. Whether it's the muddy riverbank or the haunted eyes of a teenage private, these images serve as the only bridge we have to a two-day span in 1862 when the world seemed to end in a small corner of Tennessee.

Digging through these archives isn't just about "military history." It’s about not letting these people be forgotten just because they lived in an era before "live-streaming" was a thing. Go to the Library of Congress website, type in the keywords, and just look. Really look. The details are in the shadows.

Next Steps for Your Research:

Start by searching the Library of Congress Civil War Collection specifically for "Pittsburg Landing." Compare the 1862 "aftermath" shots of the landing with modern photos from the National Park Service to see how much the Tennessee River has shifted the shoreline over the last 160 years.