It has been over a decade since Amy Chua published a book that basically set the entire parenting world on fire. If you weren't around for the initial explosion, it’s hard to describe how intense the backlash was. People weren't just disagreeing; they were calling for her arrest. They were calling her a child abuser. Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother wasn't just a memoir about a Yale Law professor raising her daughters; it became a cultural Rorschach test for how we view success, childhood, and the American Dream.

The controversy started with a Wall Street Journal excerpt titled "Why Chinese Mothers Are Superior." It was a marketing masterstroke and a public relations nightmare. In it, Chua listed things her daughters, Sophia and Lulu, were never allowed to do: attend a sleepover, have a playdate, watch TV, play video games, choose their own extracurriculars, or get any grade less than an A. People lost their minds.

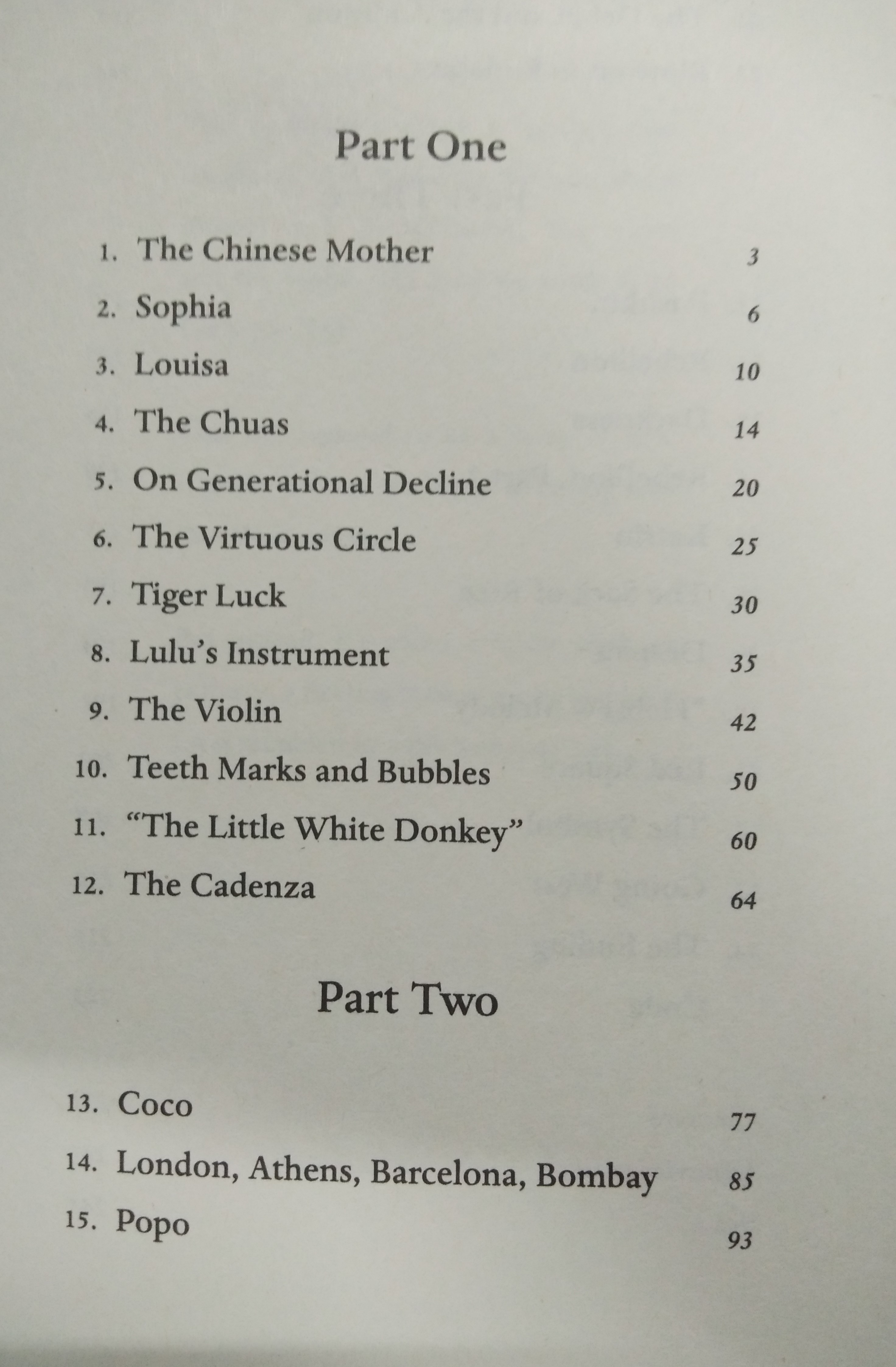

But here is the thing: most people who hated the book never actually read the whole thing. They read the headlines. If you sit down with the actual text, it’s a lot more complicated. It’s actually a story of failure. It’s a self-satirizing look at a woman who pushed so hard that her younger daughter eventually revolted, leading to a massive blowout in a restaurant in Russia. It's about a mother realizing that her "tiger" methods had a breaking point.

What Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother Actually Says (And What It Doesn't)

When we talk about the Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother, we have to talk about the "Little White Donkey." This is the infamous scene where Chua describes forced piano practice for her daughter Lulu. Lulu couldn't get a difficult piece right. Chua threatened to take away her dollhouse, then her birthdays, then her Christmas and Hanukkah presents. She called her daughter "garbage" for not trying hard enough.

It sounds horrific. Honestly, on paper, it is.

But Chua’s argument—and the core of the tiger parenting philosophy—is that nothing is fun until you’re good at it. To get good at anything, you have to work. Children, left to their own devices, will often quit the moment something gets hard. By forcing them through the "hump" of difficulty, the parent gives the child the gift of confidence. Once Lulu finally mastered the piece, she was beaming. She wanted to play it again and again. That is the "tiger" payoff. It’s about building mastery.

There's a massive cultural divide here. Western parenting often prioritizes self-esteem, assuming that confidence comes from praise. Chua argues that confidence comes from actual achievement. She believes the Western "everyone gets a trophy" model actually does kids a disservice because it doesn't prepare them for a world that doesn't care about their feelings.

The Western vs. Eastern Dichotomy

Chua used "Chinese Mother" as a loose term. She acknowledged that many Western parents are "tigers" and many Asian parents are "Western." But the tropes she leaned into were stark.

👉 See also: Images of Thanksgiving Holiday: What Most People Get Wrong

- Western parents worry about their children’s psyches.

- Tiger parents assume their children are strong enough to handle criticism.

- Western parents try to find what their kids are naturally good at.

- Tiger parents believe excellence is a matter of effort, not just innate talent.

She isn't saying one is 100% right and the other is 100% wrong. The book is a memoir, not a manual. It’s her personal account of trying to reconcile her own upbringing with the reality of raising two high-willed daughters in America.

The Fallout and the "Redemption" Arc

The internet didn't care about the nuance. Chua received death threats. People predicted her daughters would grow up to be robotic, resentful, or suicidal. The narrative was that these girls were being hollowed out by a narcissistic mother.

Except that didn't happen.

Sophia and Lulu Chua-Rubenfeld grew up. They went to Harvard. Sophia became a JAG officer in the military. Lulu graduated from Harvard Law. Most importantly, they both seem to actually like their mother. Sophia even wrote an open letter defending her mom, saying that her parents gave her the tools to live a meaningful life. She claimed that having a tiger mom made her more independent, not less.

It’s an uncomfortable reality for the critics. If the "victim" says they weren't a victim, where does that leave the outrage?

Of course, we have to acknowledge the survivorship bias here. The Chua-Rubenfeld girls were born into extreme privilege. Their parents were both professors at Yale. They had resources that most families can’t even imagine. It’s a lot easier to be a "tiger" when you have a safety net the size of a football field. For a family struggling to make rent, screaming at a child to practice violin for six hours isn't just "strict"—it’s impossible.

The Psychological Cost of Mastery

We can’t ignore the data on high-pressure parenting. While Amy Chua’s daughters turned out fine, many others don't. Studies on "perfectionistic" parenting show a direct link to higher rates of anxiety and depression in adolescents.

✨ Don't miss: Why Everyone Is Still Obsessing Over Maybelline SuperStay Skin Tint

Dr. Suniya Luthar, a psychologist who studied high-achieving schools, found that students in these environments are now considered a "vulnerable" group, similar to kids in foster care or poverty, due to the immense pressure to succeed. When your entire worth is tied to your GPA or your seat in the first-chair violin section, a single failure can feel like a total collapse of identity.

Chua’s book barely touches on the mental health aspect. She focuses on the results. But for many readers, the ends don't justify the means. Is a Harvard degree worth a fractured relationship? For Lulu, the "rebellion" was necessary. She eventually quit the violin and took up tennis. She forced her mother to back off. The book ends with a kind of uneasy truce. It’s a messy, human conclusion that doesn't offer easy answers.

Why We Still Talk About It

Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother remains relevant because the anxiety that fueled it hasn't gone away. If anything, it’s worse. Parents today are more terrified than ever that their children won't be able to compete in a global economy. We see this in the "college admissions scandal," where wealthy parents literally committed crimes to get their kids into elite schools.

We are living in an era of "intensive parenting." Whether you’re a "Tiger Mom," a "Helicopter Parent," or a "Snowplow Parent," the underlying motivation is the same: fear. We are afraid our kids won't be okay.

Chua just said the quiet part out loud. She admitted to the obsession with prestige. She admitted to the grueling hours. She didn't wrap it in the soft language of "wellness" or "holistic development." She called it what it was: a battle.

The Evolution of the Conversation

In the years since the book, the conversation has shifted. We now talk more about "gentle parenting" and "authoritative" versus "authoritarian" styles.

- Authoritative: High expectations, but high warmth. (The gold standard in psychology).

- Authoritarian: High expectations, low warmth. (Where many place the Tiger Mother).

- Permissive: Low expectations, high warmth.

- Neglectful: Low expectations, low warmth.

Chua would argue she provided high warmth—it just looked different. To her, the "warmth" was the time she spent sitting by the piano for hours. It was the belief that her children were capable of greatness. She didn't let them give up because she loved them. That’s her perspective, anyway.

🔗 Read more: Coach Bag Animal Print: Why These Wild Patterns Actually Work as Neutrals

Re-evaluating the "Success" Metric

What does it actually mean to be successful? Is it the Harvard degree? Is it the JAG officer commission?

If you look at Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother through the lens of 2026, the definition of success is broader. We care about emotional intelligence. We care about resilience—not the kind built by screaming, but the kind built by navigating adversity with support.

Interestingly, Amy Chua's later work, like The Triple Package, tried to zoom out and look at why certain groups in America succeed more than others. She identified three traits: a superiority complex, insecurity, and impulse control. It’s a controversial framework, but it points to the same obsession with the mechanics of achievement.

The reality is that parenting is an experiment with a sample size of one (or two, or three). What worked for Sophia might have broken a different child. What Lulu rebelled against might have been exactly what another kid needed to feel secure.

Actionable Insights for the Modern Parent

You don't have to be a tiger to raise a successful child, but you can borrow some of the "tiger" grit without the "tiger" trauma.

- Focus on effort over talent. When your kid does well, don't say "You're so smart." Say "I saw how hard you worked on that." This builds a growth mindset.

- Set boundaries on "quitting." Don't let a child quit a sport or instrument in the middle of a season when things get hard. Let them finish the commitment, then decide if they want to continue. This teaches them to push through the "hump."

- Distinguish between your goals and theirs. This was Chua's biggest hurdle. It’s easy to project your own needs for validation onto your children. Ask yourself: Am I pushing them for their future, or for my ego?

- High warmth is non-negotiable. No matter how high your expectations are, your child needs to know that your love isn't conditional on their report card. This is where many "tiger" critics feel Chua failed.

- Model the behavior. If you want a disciplined child, be a disciplined parent. Show them what it looks like to work hard at your own craft.

Ultimately, Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother is a book about a mother who loved her children fiercely and, in her own words, "did everything wrong" and yet somehow, they turned out okay. It’s a reminder that there is no perfect way to raise a human being. We are all just guessing, hoping that the choices we make today don't require too much therapy for our kids tomorrow.

If you’re looking to find a middle ground, start by looking at your own motivations. Are you parenting out of fear or out of a genuine desire to see your child flourish as an individual? The answer to that is more important than how many hours they spend practicing the violin.