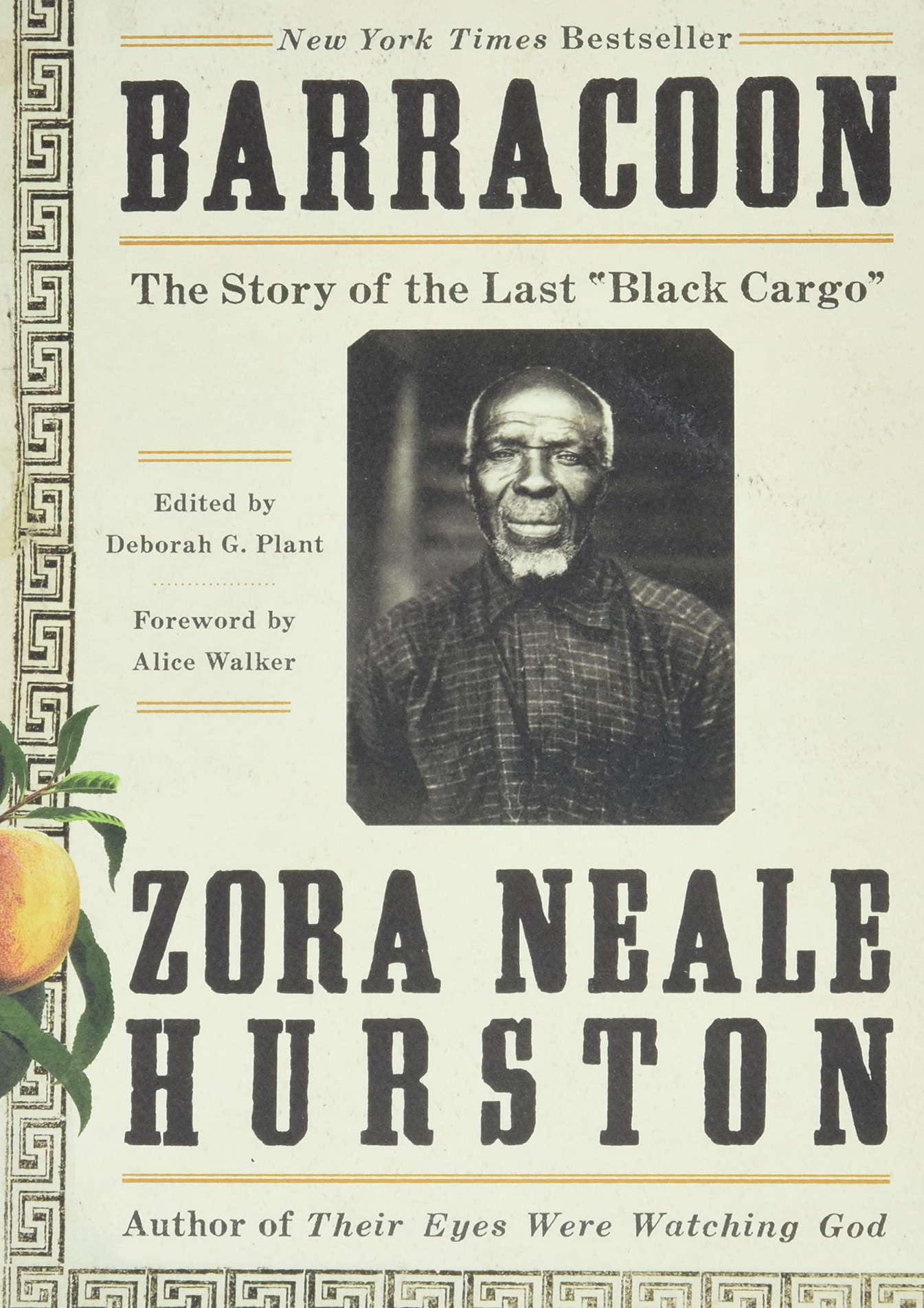

Zora Neale Hurston didn't just write a book. She sat on a porch in Plateau, Alabama, and shared peaches with an old man who had seen the absolute worst of humanity. That man was Oluale Kossola, known to his neighbors as Cudjo Lewis. For decades, the manuscript of Barracoon: The Story of the Last Black Cargo sat in a vault, gathering dust because publishers were too afraid of its raw, unedited dialect. They wanted Hurston to "fix" the way Cudjo talked. She refused. She knew that if she changed his words, she would be stealing his voice a second time.

It’s a heavy read. Honestly, it’s gut-wrenching. But it’s probably the most important firsthand account of the Transatlantic slave trade we have, mostly because it bridges the gap between the "history" we learn in textbooks and the lived reality of a human being who was still alive in 1935.

The Illegal Voyage of the Clotilda

Most people assume the slave trade ended way before the Civil War. Legally, it did. The United States banned the importation of enslaved people in 1808. But money has a way of making people ignore the law. In 1860, a wealthy shipbuilder named Timothy Meaher made a bet that he could sneak a "cargo" of humans past the federal authorities.

He did.

The ship was the Clotilda. It’s a name that haunts Alabama history. The Clotilda sailed to the Kingdom of Dahomey, bought 110 West Africans, and hauled them back to Mobile. This wasn't some ancient event. This happened just a year before the first shots were fired at Fort Sumter.

Kossola was one of those 110 people. He wasn't just a "slave" in a general sense; he was a young man with a family, a home, and a specific culture in West Africa who was violently uprooted for a rich man’s wager. When the ship arrived in Alabama, Meaher burned it to hide the evidence of his crime. The wreck of the Clotilda was actually found in the muddy waters of the Mobile River in 2019, proving that everything Kossola told Hurston was 100% true.

Why Hurston’s Dialect Matters

If you pick up Barracoon: The Story of the Last Black Cargo, you’ll notice right away that it’s written phonetically. Hurston captures Kossola’s specific accent—a mix of his native Yoruba roots and the English he was forced to learn.

💡 You might also like: Why Every Mom and Daughter Photo You Take Actually Matters

"I want to know who eat de rest at de dinner," he might say.

Some critics back in the 1930s thought this made Black people look "uneducated." They were wrong. Hurston was an anthropologist. She understood that language is identity. By preserving his speech, she preserved his soul. It takes a second for your brain to adjust to the rhythm of the text, but once you do, it feels like you're sitting there with them. You can almost feel the Alabama heat and hear the cicadas.

Kossola tells stories of his life in Africa that are incredibly vibrant. He talks about his grandfather, his initiation rites, and the terrifying moment his village was raided by the Dahomian army. It’s not just a story of suffering. It’s a story of a lost home. That’s the nuance people often miss. He didn't just miss "freedom"; he missed a very specific version of himself that died the moment he was put in that barracoon—the holding pen for captives on the African coast.

The Loneliness of the Last Survivor

One of the most heartbreaking parts of the book isn't the Middle Passage. It's the aftermath. After the Civil War ended and the enslaved people were "freed," the Clotilda survivors found themselves in a weird limbo. They couldn't go home. They didn't have money.

So, they did something incredible.

They pooled their money, bought land from the very man who had enslaved them, and built their own community: Africatown. It still exists today. But as the years went by, the other survivors died off. By the time Hurston found him in the late 1920s, Kossola was essentially the last one left who remembered the voyage.

📖 Related: Sport watch water resist explained: why 50 meters doesn't mean you can dive

He tells Hurston about the loss of his wife and his children. His grief is layers deep. He’s grieving his family, his youth, and his entire homeland. There’s a specific moment in the book where he stops talking and just weeps. Hurston doesn't try to comfort him with empty words. She just waits. She shows us a man who is profoundly lonely, even in a community he helped build.

Africatown and the Legacy of the "Last Cargo"

You can't talk about Barracoon: The Story of the Last Black Cargo without looking at what happened to Africatown. For a long time, the story was treated like a local legend or a tall tale. The Meaher family remained prominent in Mobile. The descendants of the Clotilda survivors stayed in the area, often living in the shadow of the industrial plants that eventually encroached on their land.

The discovery of the ship in 2019 changed everything.

It validated the oral history that had been passed down for generations. It turned "Cudjo's story" into an undeniable physical fact. Today, there’s a massive effort to preserve Africatown and tell the story of the Clotilda through a more modern lens, focusing on environmental justice and historical preservation.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Book

A common misconception is that this is a "slavery book" in the style of Uncle Tom's Cabin or even Twelve Years a Slave. It’s not. It’s much more personal and much less focused on the politics of the era. Kossola doesn't talk about Abraham Lincoln or the Emancipation Proclamation in the way you’d expect. He talks about the hunger. He talks about the shame of being naked in front of strangers. He talks about the confusion of being told he was free but having nowhere to go.

It's a book about memory.

👉 See also: Pink White Nail Studio Secrets and Why Your Manicure Isn't Lasting

Kossola was terrified that when he died, the memory of his people in Africa would die with him. That’s why he talked to Hurston. He wasn't seeking fame—he was seeking a witness.

Realities of the Dahomey Raids

The book is also controversial because it doesn't shy away from the role of African kingdoms in the slave trade. Kossola describes in terrifying detail how the Dahomey tribe raided his village. This is a point of history that often gets glossed over because it's "complicated." But Hurston includes it because it was Kossola's truth.

The Dahomey were a powerful military state that grew wealthy by capturing neighbors and selling them to Europeans and Americans. Acknowledging this doesn't diminish the horror of American chattel slavery; it just adds a layer of tragic complexity to the global machine that chewed up people like Kossola.

Actionable Insights for Readers and History Buffs

If you’re interested in diving deeper into this history, don't just stop at the book. The story is still unfolding in real-time.

- Read the 2018 HarperCollins Edition: This version includes a brilliant introduction by Deborah G. Plant that provides the necessary context on why it took so long for the book to be published.

- Research the Clotilda Discovery: Look into the work of the Alabama Historical Commission and the Search for the Clotilda. They have amazing underwater footage and archaeological findings that bring Kossola’s words to life.

- Visit or Support Africatown: If you’re ever near Mobile, Alabama, the Africatown Heritage House is a must-see. It houses artifacts from the ship and tells the story from the perspective of the descendants.

- Watch the Documentary "Descendant": It’s available on Netflix and follows the community of Africatown as they navigate the discovery of the Clotilda. It serves as a perfect visual companion to Hurston’s book.

- Look into Zora Neale Hurston’s Anthropological Work: Beyond her famous novel Their Eyes Were Watching God, her field research in the American South is a goldmine of Black folklore and history that was nearly lost to time.

Barracoon: The Story of the Last Black Cargo serves as a bridge. It connects the 19th-century slave ships to the 20th-century Jim Crow South and, ultimately, to our 21st-century understanding of ancestry and justice. It’s a short book, but it stays with you forever. It reminds us that history isn't just a list of dates; it’s the sound of a man’s voice, cracked with age, trying to make sure his mother’s name isn't forgotten.