Ever woken up and just felt the rain coming? It’s not a superpower. Well, maybe a little one. Your joints are essentially acting as organic barometers, reacting to the invisible weight of the atmosphere pressing down on you every single second. Most people think about weather as just "wet" or "sunny," but the real story is written in barometric pressure.

It’s heavy.

💡 You might also like: Recipe for a Healthy Salad Dressing: Why Most Store-Bought Versions Are Trash

Air actually has weight. If you’re standing at sea level, you have about 14.7 pounds of air pressing against every square inch of your body. When we talk about high or low pressure, we are talking about the weight of that column of air stretching from your head all the way to the edge of space. When that weight shifts, your body notices. Your sinuses notice. Even your mood takes a hit.

The Science of Low Pressure: Why the "Drop" Hurts

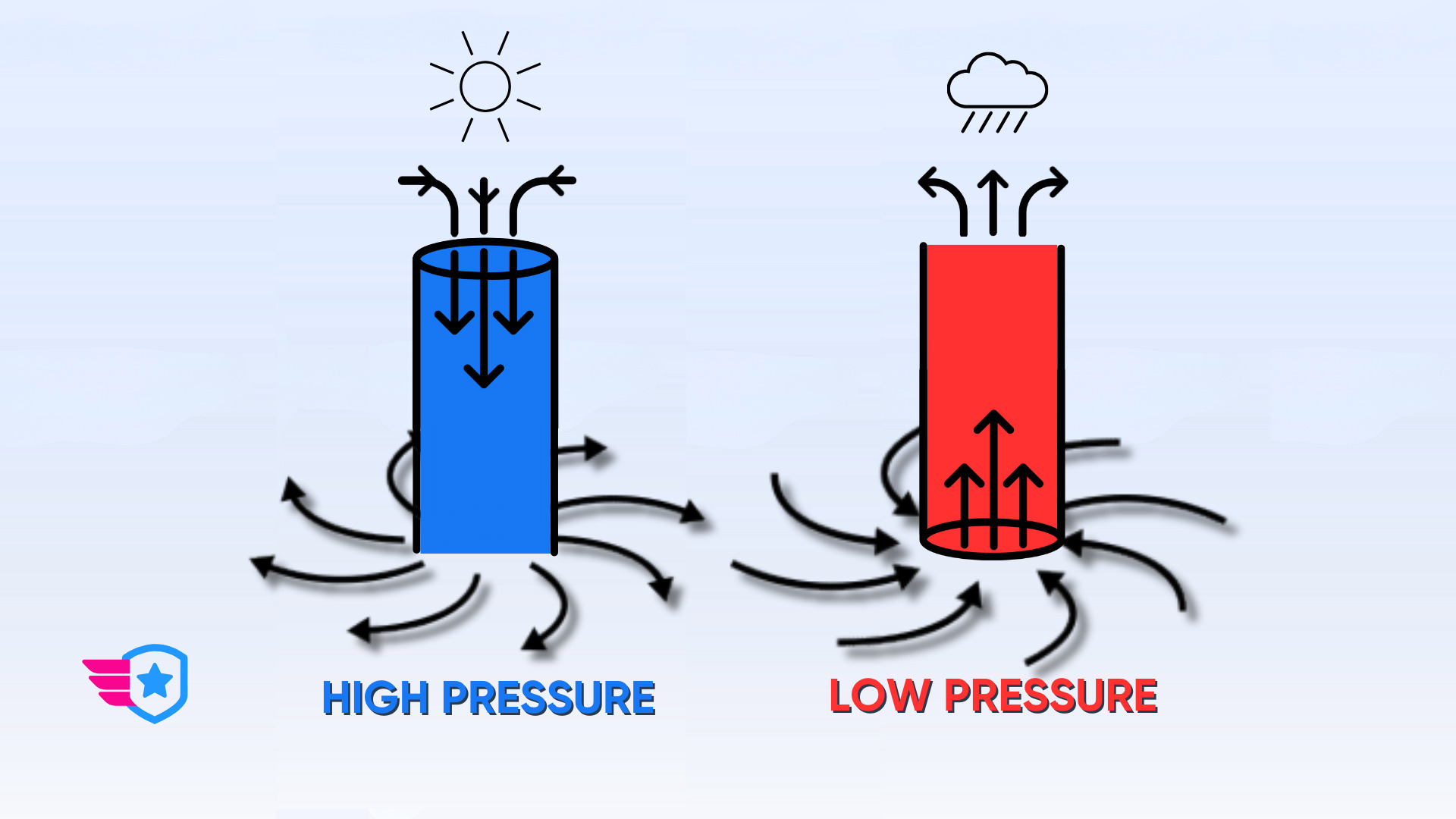

Low pressure usually means a storm is rolling in. Meteorologically, it happens when air rises. As that air lifts, it cools, water vapor condenses, and you get clouds or rain. But inside your body, something else is happening. Think of your joints like small balloons. When the external pressure (the weight of the air) drops, those "balloons" expand.

This isn't just a theory for the elderly. A 2017 study published in the British Medical Journal actually looked at over 11 million visits to doctors and found a correlation between rainfall and joint pain, though they noted it’s complex. But if you ask anyone with rheumatoid arthritis or even just a healed sports injury, they’ll tell you the 2017 study doesn't tell the whole story. Dr. Robert Shmerling of Harvard Health notes that while the data is sometimes "cloudy," the physiological mechanism of tissue expansion in response to falling barometric pressure is sound.

When the atmospheric pressure decreases, it exerts less force against your body. This allows your tissues to slightly swell. This microscopic expansion can irritate nerves. If you have an area with chronic inflammation, that tiny bit of extra room for the tissue to expand translates into a dull, throbbing ache.

It’s literally the weather pushing—or not pushing—on you.

High Pressure and the Clear Sky Trap

High pressure is usually the "good" weather. It’s when cool air sinks, suppressing cloud formation and giving us those crisp, blue-sky days. You’d think this would be the gold standard for feeling great.

📖 Related: Free NCLEX Practice Test: Why Most Students Are Studying All Wrong

Not always.

High barometric pressure can be a nightmare for people with certain types of migraines. While low pressure is the more famous trigger, sudden spikes in pressure can be just as disruptive. Your body craves homeostasis. It wants things to stay the same. When the air becomes "heavy" during a high-pressure system, it can affect the pressure gradients in your inner ear and sinuses.

Basically, your head is a series of air-filled cavities. If the pressure outside changes faster than your body can equalize the pressure inside those cavities, you get a headache. It’s the same feeling as when your ears pop on a plane, just slower and more persistent.

Blood Pressure and the Atmospheric Connection

Here is something most people miss: the weather affects your heart.

Researchers have long observed that blood pressure readings tend to be higher in the winter and lower in the summer. Part of this is the cold—vasoconstriction—but high or low pressure plays a role too. When barometric pressure is low, your blood viscosity can change.

Some clinical studies suggest that low pressure can lead to a slight drop in blood pressure, which might sound good, but for someone already prone to hypotension, it leads to dizziness and fatigue. Conversely, high-pressure systems are often associated with thicker air and more oxygen, but they can also trap pollutants close to the ground. This "stagnant" air is a major trigger for asthma and respiratory issues.

The Mystery of the "Weather Mood"

Why does a gray, low-pressure day make you want to eat a loaf of bread and nap for six hours?

It’s partly light, sure. But there’s a biological tug-of-war happening. Low barometric pressure is often linked to a decrease in serotonin levels. While the exact "why" is still being debated in neurobiology circles, the correlation is hard to ignore. When the pressure drops, we see an uptick in hospital admissions for psychiatric emergencies and a general dip in community mood scores.

You aren't just "sad because it's raining." Your brain chemistry is reacting to a physical change in your environment.

Managing the Shifts: Real World Steps

You can't change the weather. Unless you move to San Diego, you’re stuck with the swings. But you can mitigate how your body reacts to high or low pressure changes.

Hydration is non-negotiable. When pressure shifts, your fluid balance shifts. Keeping your blood volume stable helps your body adjust to those external pressure changes faster.

Watch the barometer, not just the temp. Apps like Barometer Pro or even the built-in sensors on many modern smartphones can tell you when a "cliff" is coming. If you see the pressure dropping fast, that’s the time to take your anti-inflammatories before the pain starts. Proactive management is 10x more effective than reactive.

Movement. If low pressure is causing your tissues to expand and joints to ache, the worst thing you can do is stay still. Gentle movement helps circulate synovial fluid, which lubricates the joints and can offset some of that pressure-induced stiffness.

Sinus Care. If you’re a pressure-headache sufferer, keep a saline spray or a Neti pot handy. Keeping those passages clear makes it much easier for your internal cavities to equalize with the outside air.

The atmosphere is a heavy, moving ocean of gas. We just happen to live at the bottom of it. Understanding that your body is a pressurized vessel helps take the mystery out of why you feel "off" when the clouds roll in. It’s not in your head—it’s the weight of the world, quite literally, shifting on your shoulders.

To stay ahead of the next shift, start tracking your "pain days" against a local barometric pressure log. You’ll likely find a pattern that allows you to predict your own flare-ups better than any meteorologist could.